By 1774 Edward Winslow could not see any chance for compromise. To him the Sons of Liberty were enemies of his class—” Sons of Licentiousness,” a “sett of cursed, venal, worthless Raskalls.” His words earned him a severe rebuke from a radical new local authority, the Plymouth County Convention, which charged that he had “betrayed the trust reposed in him” because of his openly Loyalist sympathies. Winslow, fearing the end of the Plymouth that his dynasty had created and preserved, showed more than mere sympathy to Tory views. He believed that a civil war was breaking out and that Loyalists had to fight the Rebels (a label that the Sons of Liberty despised) to save the king’s colonies. Winslow met secretly with Governor Hutchinson, who authorized him to raise and maintain a “Tory Volunteer Company.”

This was not yet a Loyalist call to arms. Winslow wanted a security force that could protect citizens from roaming mobs that Loyalists called Rebels even though they often were made up of hoodlums with no greater cause than mischief or anger directed at the upper class by the lower.

The Tory Volunteer Company kept Plymouth “in quiet long after all the towns in the neighborhood were in extreme confusion,” Winslow wrote. He credited Hutchinson with approving the idea of mobilizing Loyalists. But it was Hutchinson’s successor, Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, who carried out the plan.

The arming of Loyalists was a reaction to a new wave of protests that had begun to roar across the colony on May 10, 1774, when Bostonians learned that Parliament had passed an act closing the Port of Boston. Three days later, Gage, who had been on leave in England during the Boston Tea Party, arrived in Boston. The city, at least on the surface, and at least on that day, appeared peaceable. He was escorted by the elegantly uniformed Boston Cadets, whose commander was Col. John Hancock, and he was given a noisy welcome that included three volleys of musketry and three rousing cheers.

Gage brought with him new powers bestowed by the king and the Earl of Dartmouth, principal secretary of state for North America. Gage’s traditional titles—vice admiral, captain general, and governor in chief—now in reality added up to the implicit title of military governor, for he was simultaneously royal governor and commander of British forces in North America. With the aid of the four regiments of British Army Regulars and a fleet of Royal Navy warships, he would rule over a military occupation of the city.

Although Gage’s martial rule encompassed the entire colony, he focused his power on rebellious Boston while trying to keep close watch on the towns around the city. For this, he developed allies among leading Loyalists like Winslow. In early June, Gage moved the customs commissioners and their records from Boston to the relative safety of Plymouth, where Winslow was given a stipend for providing “an Office, fuel, and candles.”8 Winslow’s work for the customs bureaucracy earned him additional umbrage from the Patriots.

Gage knew that royal authority was rapidly waning, but he refrained from imposing harsh martial law. He saw no use in trying to silence the Rebel newspapers. Freedom of the press had many defenders in Parliament, and nothing was to be gained by further inflaming the Rebels or giving Parliament another issue to debate. To prevent incidents he had ordered his officers not to wear sidearms. They thought that he was kowtowing to the Rebels. An officer, using the soldiers’ nickname for Gage, grumbled in his diary: “If a soldier errs in the least, who is more ready to complain than Tommy?”

Loyalists waited expectantly for him to crack down on the Rebels. Peter Oliver, a wealthy landowner and chief justice of the colony, hoped Gage would swiftly end the incipient rebellion by arresting Rebel leaders on charges of high treason, a hanging offense. But, Oliver added, “unhappily for the Publick, the People were disappointed & the Traitors felt their selves out of Danger.” The reason, Oliver said, was “Timidity, in Suppression of Rebellion.” Gage, a longtime soldier trying to be a governor, would try to govern by sheathing his sword and picking up a pen: There would be no immediate arrests, no curfew, no raids on Rebel meeting places.

Gage prorogued—discontinued without dissolving—the Great and General Court of Massachusetts and moved it from turbulent Boston to quieter Salem. Voters boldly responded by electing a provincial congress to replace the General Court. Gage canceled his call for a new legislative session. But the representatives kept meeting as a body. It was recognized by Patriots but not by Loyalists, although men of both persuasions were among the members.

Sam Adams, looking beyond protests and mob action, wanted the legislature to vote to send delegates to a congress2 that would take up the Patriot cause. He knew that Gage would dissolve the legislature if his Loyalist informers heard of Adams’s plan. On June 17, after secretly revealing his intentions to a few Patriot legislators, Adams moved that the legislature appoint a five-man delegation to a Continental Congress to meet in Philadelphia beginning on September.

Before any Loyalists could dash for the door, Adams locked it and pocketed the key, only relenting when a Tory member claimed to be ill and needed to leave.

The suddenly cured delegate ran to find Gage, who immediately wrote an order dissolving the legislature and dispatched his secretary to the legislative chamber. When no one would admit him, the secretary read the order to some people standing in the outside hall. Behind the locked door the legislators voted 117 to 12 to send Sam Adams and John Adams to Philadelphia, along with Robert Treat Paine, a Patriot leader in Taunton, a Tory stronghold about thirty-five miles south of Boston; Thomas Cushing, a prominent Boston lawyer; and James Bowdoin, a wealthy Harvard graduate who shared with Ben Franklin an interest in electricity and the phosphorescence of the sea.

The Virginia House of Burgesses in Williamsburg had also been officially shut down. But defiant members, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry, met at the nearby Raleigh Tavern and declared support for Massachusetts by agreeing not to import British goods. The declaration defied traditional British policy, which frowned on collaboration among colonies. In New York a committee consisting mostly of merchants also responded to Boston’s appeal. Committees of Correspondence kept the idea moving through the colonies. The result would be the First Continental Congress, attended by delegates from all the colonies except Georgia, the newest and least populous.

Members of the Massachusetts General Court’s council, which served as a kind of upper house, had been elected in the past. Acting under the new law, Gage appointed members instead. The appointees were known as “mandamus councillors,” a reference to a royal writ of mandamus, from the Latin for “we command.” Gage nominated thirty-six councillors. Twelve immediately declined, and most of those who remained swiftly resigned, fearing retribution from the Sons of Liberty.

Similarly, when Gage appointed royal judges, many declined to serve. And those who did agree to take the bench discovered that they could not empanel juries because men who were summoned, including Paul Revere, would not even enter the courtroom. In some places people blockaded the courthouses. In Barnstable, on Cape Cod, for example, a crowd of about twelve hundred men gathered in front of the Court of Common Pleas and refused to allow the chief justice to enter after he demanded passage in the king’s name. The confrontation ended peacefully. But royal governance was disappearing from courthouses, just as it had from the legislature. All “civil Government, both Form & Substance,” had ended, Peter Oliver lamented. “The People now went upon modeling a new Form of Government, by Committees and Associations… . The wild Fire ran through all the Colonies.”

The minutes of town meetings in Worcester, forty miles west of Boston, show how conflicts over the Intolerable Acts were turning neighbor against neighbor during that restive summer of 1774. Back in March, when Worcester held its annual meeting, townspeople voted to boycott tea until the tea tax was repealed. Twenty-six “Royalists” voted against the boycott. Shortly afterward forty-three people, all labeled Royalists, signed a petition to reconsider the vote. After a long and bitter debate in June, the petition was defeated.

Now, with Gage in the governor’s chair, the Worcester Royalists were emboldened. Determined to air their beliefs, they filed with the town clerk a long statement that began by lamenting how “sober, peaceable men” in their town had been “deceived, deluded and led astray by the artful, crafty and insidious practices of some evil-minded and ill-disposed persons.” The Royalists’ statement denounced the tea dumpers in Boston and attacked the Committees of Correspondence, whose “dark and pernicious” actions were leading people toward “sedition, civil war, and Rebellion.”

The town clerk, to the astonishment of the Worcester Patriots, allowed the statement to be treated like any other public document. The Boston Gazette learned of the statement and published it on July 4. The Worcester Patriots, enraged, plotted retaliation.

On August 22 a large force of men from Worcester and area towns, unarmed but marching “in military order,” assembled on the town common. A committee called on Timothy Paine, a mandamus councillor and father of a notorious Tory. Paine, fearing violence, agreed to resign. The marchers—a history of the town puts their number at three thousand—then headed for Main Street and formed a gauntlet that extended from the courthouse to the meetinghouse. A crowd gathered, wondering what was going on. Patriots pulled Royalists out of the crowd and pushed them into the gauntlet with Paine, forcing them all to stop frequently to read aloud their “acknowledgment of error and repentance.”

Next, a smaller force—about five hundred men, according to the town history—headed for nearby Rutland and demanded the resignation of another new councillor, James Putnam, a fifty-year-old fifth-generation American. A renowned lawyer, he had served as a major in the French and Indian War. John Adams had boarded in Putnam’s home and studied law under him for two years while teaching school in Worcester. Putnam had been the leader of the Worcester group that had signed the anti-Patriot statement. He was not home when the protesters arrived, so one of them handed a member of his family a letter ordering Putnam to publish his resignation in Boston newspapers.

Another mob, armed with clubs and muskets and numbering some fifteen hundred, confronted Daniel Murray, a designated councillor from Rutland, and demanded his promise to resign. They menaced him at first. But he was surprised to see them disperse “without doing the least damage to any part of the estate.” Still, the roving mobs frightened area Loyalists, several of whom collected firearms, ammunition, and food and gathered at Stone House Hill in Worcester, setting up defenses and transforming the house into what became known as the Tory Fort. They stayed there for about three weeks, awaiting a Patriot attack that never came.

Putnam and scores of other Loyalists were also reviled as “Addressers” because they had signed printed copies of flowery statements, called “addresses,” lauding Gage after his arrival on May 13, 1774, and Hutchinson, prior to his departure on June 1. One address to Hutchinson expressed “the entire satisfaction we feel at your wise, zealous, and faithful administration.” An equally flattering tribute was presented to Gage, hailing him for his “experience, wisdom and moderation, in these troublesome and difficult times.”

A broadside published by the Patriots identified the 123 Addressers of Hutchinson, including relatives of placemen and artisans, such as jewelers and makers of chaises (open carriages, often with collapsible hoods), whose leading customers were Loyalists. Of the Addressers, 14 were officers of the Crown, and 63 were merchants.

Many Patriot tradesmen refused to serve Loyalists. Forty-three blacksmiths in Worcester County, for example, proclaimed that they would not do any work “for any person or persons commonly known by the name of tories.” The blacksmiths urged other Patriots “to shun their vineyards” and “withhold their commerce and supplies.”

Some of the Addressers attempted to ward off trouble by apologizing for “that unguarded action of ours,” hoping that their acts of contrition would restore them as “Partakers of that inestimable blessing, the good Will of our Neighbours, and the whole Community.” Repentance did little good. They were all marked men; even those who rejected Gage’s offer were denounced or threatened.

The Patriots declared that no one should deal with mandamus councillors in any way. Jessie Dunbar, of Bridgewater, twenty miles west of Plymouth, defied the edict by buying livestock from Nathaniel Ray Thomas, a councillor and a leading Tory in Marshfield, thirty miles south of Boston. The original Edward Winslow had founded Marshfield in 1640. A road built then, connecting Plymouth with Marshfield, was probably America’s first; stretches of it still exist as the Pilgrim Trail. The original Winslow sold the original Thomas a large swath of Marshfield land, and the two families, generation after generation, remained connected there, by road and by heritage.

Dunbar drove the animals he had bought from Thomas to Plymouth, where he skinned an ox and hoisted the carcass up on a rack for sale. Men who identified themselves as Sons of Liberty soon appeared, cut down the carcass, put it in a cart, and forced Dunbar into the ox’s sliced-open belly. They “carted” him, as they called the ordeal, for about four miles, charged him a dollar for the ride, and then handed him over to a new mob whose members carted him for several more miles, extracted another dollar from him, and passed him on to a third mob in Duxbury. There his tormentors yanked him from the ox’s belly, then reached in to pluck out the beast’s entrails, which they used to whip him about his body and face.

Duxbury bordered on Plymouth and had been settled in 1632 by Mayflower passengers, including storied Miles Standish. Loyalists in Duxbury reported that the local militia had spawned a number of “Minute Men,” volunteers who vowed to be ready to go into battle at a minute’s warning. The First Massachusetts Provincial Congress had directed that one-third of each militia consist of men and officers ready and equipped to respond swiftly to an alarm. Other colonies copied the Massachusetts system in various ways.

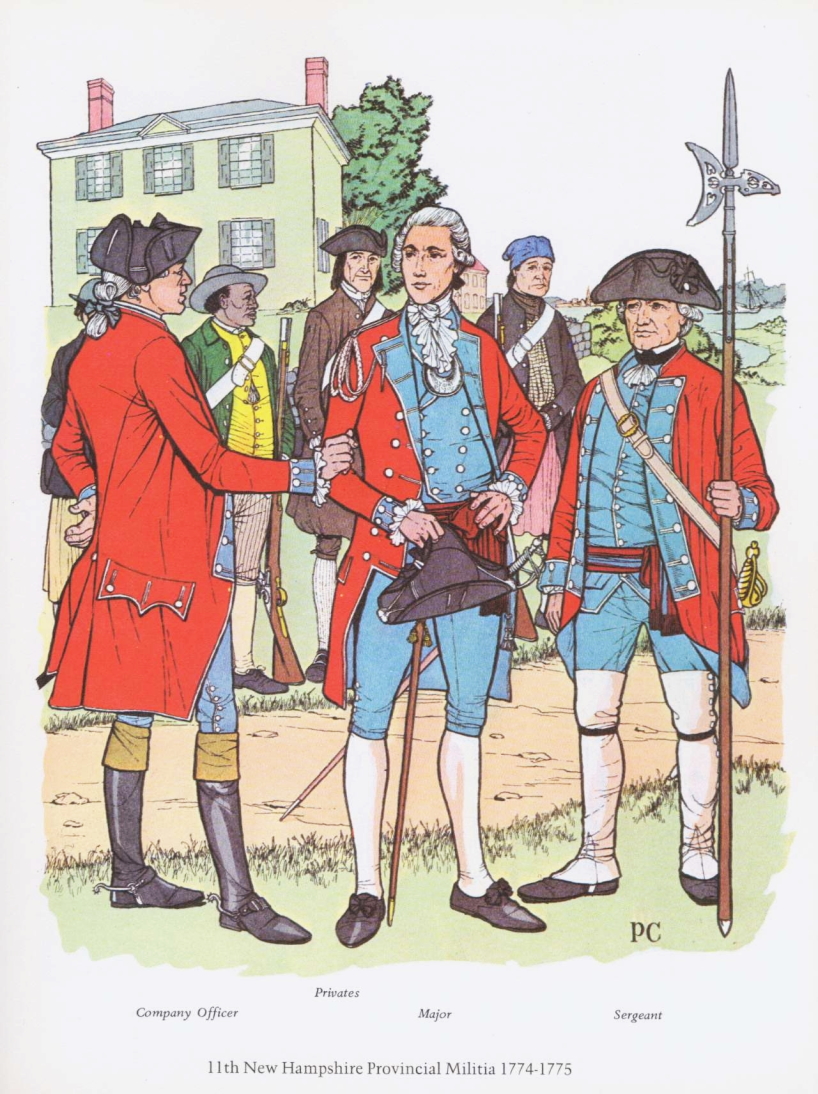

Until the Revolution militias were royal military units, usually commanded by wealthy and influential officers commissioned by the Crown. As Patriots began rising to power, they formed provisional governments whose revolutionary acts included the abolition of royal militias. Many militiamen became self-appointed enforcers, harassing Tories and policing boycotts. The First Continental Congress urged Patriot leaders to control local militias. The second went further, advocating the election of militia officers and suggesting that militia companies form themselves into regiments controlled by elected provincial governors and legislatures. Loyalists eventually reacted by forming their own military units.

Gage undoubtedly knew about the spreading minuteman movement through his intelligence network of Tory spies and informers. But, without disclosing his own knowledge, he politely replied to a letter of concern from Duxbury justices, promising that he would “take every step” in his power to “secure to them the peceable enjoyment of all their constitutional privileges.”

One of the mandamus councillors who did not resign was Daniel Leonard, a thirty-four-year-old lawyer from Taunton. While representing Taunton in the legislature in the earlier 1770s, he had been an eloquent supporter of the Patriots, even though he was the son of a Loyalist judge. But Leonard the Patriot married an heiress and, as John Adams described Leonard’s metamorphosis, “He wore a broad gold lace round the rim of his hat, he had made his cloak glitter with laces still broader, he had set up his chariot and pair… . Not another lawyer in the province … presumed to ride in a coach or chariot.” By 1774 Leonard was a committed Loyalist.

“When I became satisfied that many innocent, unsuspecting persons were in danger of being seduced to their utter ruin, and the province of Massachusetts Bay in danger of being drenched with blood and carnage,” Leonard wrote to Gage, “I could restrain my emotions no longer.”

Patriots in Taunton had tolerated Leonard until they learned that he had accepted Gage’s appointment as a councillor. A huge mob gathered near Leonard’s home and began shouting threats. Leonard’s father stepped outside the mansion. Saying his son was in Boston, he promised to try to talk Daniel into resigning. The mob dispersed. The next night a smaller group appeared and, seeing a light in a bedroom, believed that Daniel was home. Someone fired a gun. The shot shattered the window of the bedroom window, narrowly missing Daniel’s pregnant wife in her bed. When the Leonard baby was born mentally disabled, the family blamed the terrifying shot in the night.

In western Massachusetts, Gage had selected Israel Williams, a longtime legislator, to be a mandamus councillor. He, too, had declined the appointment. Nevertheless, one night a mob kidnapped the sixty-five-year-old. They brought him to a house several miles away and confined him to a room with a fireplace, locked the doors, built a fire, and then blocked the chimney. His captors kept Williams gasping for air until morning, when he stumbled out of the smoke-filled room and signed a paper that pledged his opposition to British authority.

Patriot mobs’ “smoking” treatment was so commonplace that John Trumbull used the term in references to Murray and Williams in a poem. Trumbull, a lawyer who had practiced with John Adams, was a Patriot poet best known for M’Fingal, a long poem that satirized Loyalists. It included these lines:

Have you made Murray look less big, Or smoked old Williams to a Whig?

Smoking and intimidation had mostly replaced tar and feathers, which had been the punishment of choice during Stamp Act days. The practice, which British torturers had been performing since the Crusades, was hurting the Patriot cause. “Americans were a strange sett of people,” a member of Parliament remarked in 1774, “… instead of making their claim by argument, they always chose to decide the matter by tarring and feathering.” After the Stamp Act protests died down, Patriot leaders tried to curb the mobs of Massachusetts; tarring and feathering dropped off, although one incident was well publicized.

John Malcolm, a notorious customs informer, had beaten a Boston man with a cane. On January 25, 1774, avengers put Malcolm “into a Cart, Tarr’d & feathered him—carrying thro’ the principal Streets of this Town with a halter about him, from thence to the Gallows & Returned thro’ the Main Street making Great Noise & Huzzaing.”

Redcoats in Boston chose to use the punishment on a civilian caught in a sting operation when he accepted a soldier’s offer to sell his musket. The man was stripped naked, covered with tar and feathers, placed in a cart, and escorted by fifes, drums, and about thirty grenadiers to the Liberty Tree, a venerable elm around which Patriots had been rallying since the Stamp Act protests. A large crowd of scowling citizens gathered and rescued the man as the parade about-faced and rapidly headed back to the British barracks. A protest to Gage went unanswered.

By the summer of 1774, tension between Bostonians and Redcoats was growing and violence was spreading. In July, Jonathan Sewall, the Massachusetts attorney general, talked about the crisis with his long time friend John Adams. Their legal duties happened to put them at the same time in the northern part of the colony that was called Maine. They climbed a hill in Falmouth (now Portland) and were buffeted by the breezes of Casco Bay as they spoke.

As one of the Massachusetts delegates to the Continental Congress, Adams would soon be off to Philadelphia. Sewall urged his friend not to go and to abandon the Patriot cause. “I answered,” Adams wrote in his diary, “that the die was now cast; I had passed the Rubicon. Swim or sink, live or die, survive or perish with my country was my unalterable determination.