The Invasion of Prussia

The strategies of the two commanders contrasted greatly. The grand master divided his forces in the traditional manner between East and West Prussia, awaiting invasions at widely scattered points and relying on his scouts to determine the greatest threats, his intention being to concentrate his forces quickly wherever necessary to drive back the invaders. Jagiełło, however, planned to concentrate the Lithuanian and Polish armies into one huge body, an unusual tactic. Although adopted from time to time in the Hundred Years’ War, it was more common among the Mongols and Turks – enemies the Poles and Lithuanians had fought often. The Teutonic Knights did the same during their Reisen into Samogitia, but those had been much smaller armies.

In this phase of the campaign Jagiełło’s generalship was exemplary. As soon as he heard that Vytautas had crossed the Narew River he ordered his men to build a 450-metre pontoon bridge over the Vistula River. Within three days he had brought the main royal host to the east bank, then dismantled the bridge for future use. By 30 June his men had joined Vytautas. On 2 July the entire force began to move north. The king had thus far cleverly avoided the grand master’s efforts to block his way north and even kept his crossing of the Vistula a secret until the imperial peace envoys informed Jungingen. Even then the grand master failed to credit the report, so sure was he that the main attack would come on the west bank of the Vistula and be conducted by only the Polish forces.

When Jungingen obtained confirmation of the envoys’ story he hurriedly crossed the great river with his army and sought a place where he could intercept the enemy in the southern forest and lake region, before Lithuanian and Polish foragers could fan out among the rich villages of the settled areas in the river valleys. His plan was still purely defensive – to use his enemies’ numbers against them, anticipating that they would exhaust their food and fodder more swiftly than his own well-supplied forces. The foe had not yet trod Prussian ground.

The grand master had left 3,000 men under Heinrich von Plauen at Schwetz (Swiecie) on the Vistula, to protect West Prussia from a surprise invasion in case the Poles managed to elude him again and then strike downriver into the richest parts of Prussia before he could cross the river again. Plauen was a respected but minor officer, suitable for a responsible defensive post but not seen as a battlefield leader. Jungingen wanted to have his most valuable officers with him, to offer sound advice and provide examples of wisdom, courage, and chivalry. Jungingen was relatively young, and a bit hot-headed, but all his training advised him to err on the side of caution until battle was joined. Daring was a virtue in the face of the enemy, but not before.

Jagiełło, too, was a careful general. Throughout his entire career he had avoided risks. No story exists of his ever having put his life in danger or led horsemen in a wild charge against a formidable enemy. Yet neither was there the slightest hint of cowardice. Societal norms were changing. Everyone acknowledged the responsibility of the commander to remain alive; everyone accepted the fact that the commander should guide the fortunes of his army rather than seek fame in personal combat.

Consequently it was no surprise that the king’s advance toward enemy territory was slow. His caution was understandable. After all, he could not be certain that his ruse had worked; and he had great respect for Jungingen’s military skills. Without doubt, he worried that he would stumble into an ambush and give the crossbearers their greatest victory ever. He must have been half-relieved when his scouts reported that the crusaders had taken up a defensive position at a crossing of the Dzewa (Drewenz, Drweça) River. At least he knew where Jungingen was, waiting at the Masovian border. On the other hand, the news that the grand master’s position was very strong could not have been welcome.

So far each commander had moved cautiously toward the other. Jagiełło and Jungingen alike feared simple tactical errors, such as being caught by nightfall far from a suitable camping place, or having to pass through areas suitable for ambush or blockade; in addition, they had to provide protection for their transport, reserve horses, and herds of cattle. Although each commander was experienced in directing men in war, these armies were larger than either had brought into battle previously, and the larger the forces, the more danger there was of error, of misunderstanding orders, and of panic.

Judged by those criteria, both commanders deserve high marks for bringing their armies into striking distance of each other without having made serious blunders. Both armies were well-supplied, ready to fight, and confident of a good chance for victory; the officers all knew their opponents well, were familiar with the countryside and the weather, and in full command of the available technology. The resemblance of some formations to armed mobs was offset by martial traditions, individual unit drill, and widespread experience in local wars. Neither army was handicapped by dissensions in command, quarrels among units, unusual prevalence of illness, or excessive anxiety about the impending combat – these problems existed, but they were probably shared equally and were not serious enough to merit mention in contemporary accounts. In short, there were no excuses for failure.

For the Teutonic Knights, each commander, each officer, each knight was as ready for combat as could reasonably be expected. All that remained uncertain was how the battle would begin, how individuals would react, and how the affair would unfold – for those are unknowns always present in warfare. Though many individuals had participated in raids and sieges, few had personal experience in a pitched battle between large armies. Some crusaders may have gained sad experience at Nicopolis in 1396, and some of their opponents may have survived Vytautas’ 1399 disaster on the Vorskla in the Ukraine against the Tatars, but those would be the only ones who knew what to expect when tens of thousands of combatants came together for a few minutes of intense struggle. Only they knew first-hand that warfare on this scale was chaos beyond imagination, with commanders unable to contact more than a few units, with movement limited by the sheer numbers of men and animals on the field, with the senses overwhelmed by noise, smoke from fires and cannon, and dust stirred up by the horses, the body’s natural dehydration worsened by excitement-induced thirst, and exhaustion from stress and exertion. This led to an irrational eagerness for any escape from the tension – either flight or immersion in combat. Aside from that small number of experienced knights there was only the practice field and small-scale warfare in Samogitia, the campaign in Gotland, and the 1409 invasion of Poland. Those provided good military experience, but there had not been a set-piece combat between the Teutonic Knights and the Lithuanians for forty years, or between the Teutonic Knights and the Poles for almost eighty. Throughout all of Europe, in fact, there had been many campaigns, but few battles. For both veterans and neophytes there was consolation in storytelling, boasting, prayer, and drinking.

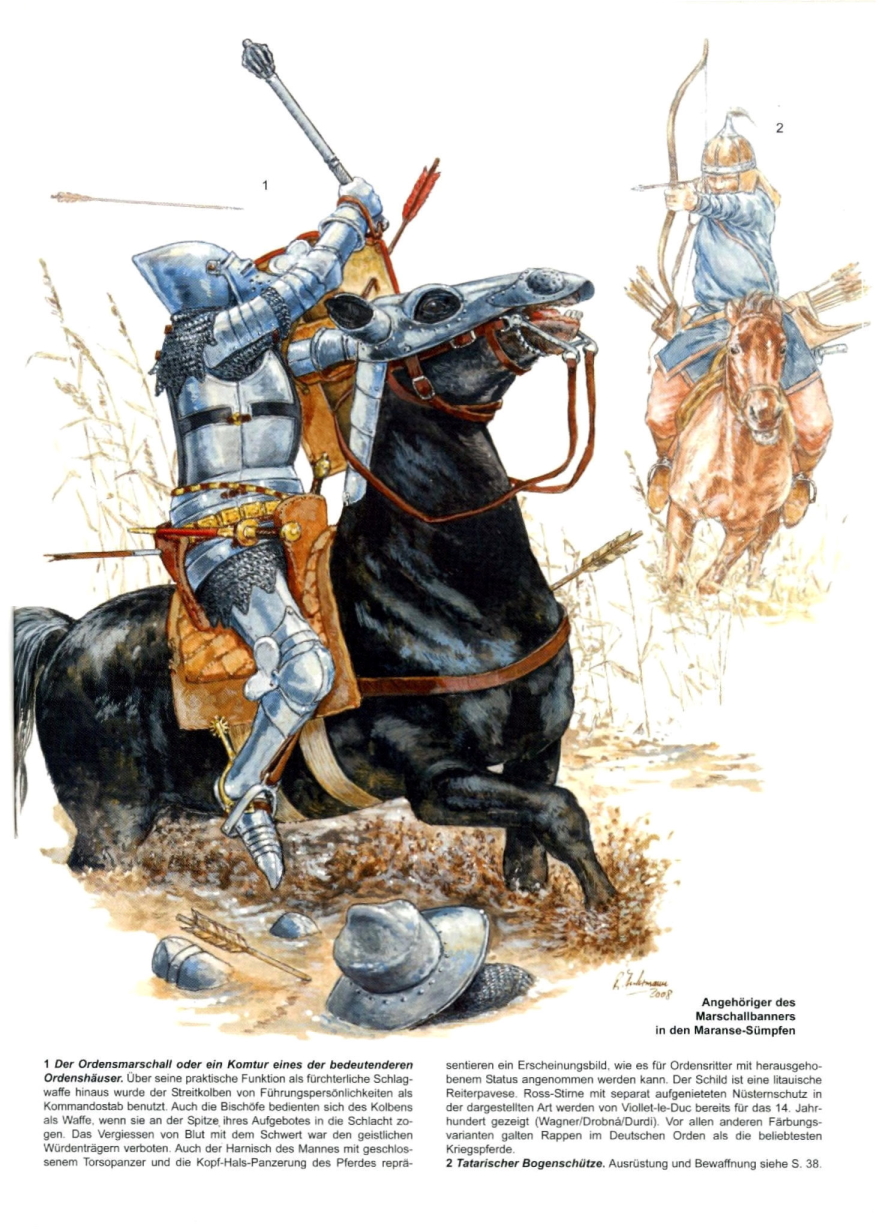

The Lithuanians were more experienced, but only in the more open warfare on the steppes and in the forests of Rus’. Riding small horses and wearing light Rus’ian armour, they were not well equipped for close combat with Western knights on large chargers, but they were equal to their enemy in pride and their confidence in their commander. Memory of Vytautas’ disaster on the Vorskla had been dimmed by subsequent victorious campaigns against Smolensk, Pskov, Novgorod, and Moscow. Between 1406 and 1408 Vytautas had led armies against his son-in-law, Basil of Moscow, three times, once reaching the Kremlin and at last forcing him to accept a peace treaty that restored the 1399 frontiers. Vytautas’ strength was in his cavalry’s ability to go across country that defensive forces might consider impassable; his weakness was that lightly-equipped horsemen could not survive a charge by heavy warhorses bearing well-armoured knights – he counted on his Tatar scouts to prevent such an event happening by surprise.

The mounted Polish forces were more numerous and better equipped for a pitched battle with the Germans, but they lacked confidence in their ability to stand up to the Teutonic Knights. The contemporary Polish historian Długosz complained about their unreliability, their lust for booty, and their tendency to panic. Most Polish knights – at least 75% – sacrificed armour for speed and endurance, but they were not as ‘oriental’ as the Lithuanians. In this they hardly differed from the majority of the order’s forces, light cavalry suitable to local conditions. Of the rest, many Polish knights wore plate armour and preferred the crossbow to the spear, just as did many of the Teutonic Knights’ heavy cavalry. The weakness lay in training and experience: many Polish knights were weekend warriors, landlords and young men; they were non-professionals who knew that they were up against the best trained and equipped troops in Christendom. Although some of them had served under the king previously, he seems to have drawn more troops from the north for this campaign than from the south; and it was the southern knights who had served with him in Galicia and Sandomir. Jagiełło could have called up more knights, but he could not have found room for them at the campsites, much less fed them. The masses of almost untrained peasant militia were much easier to manage; their noble lords could assume they would feed themselves and they could sleep outside no matter what the weather was. While the peasants’ usefulness in battle was small – at best they could divert the enemy for a short while, allowing the cavalry time to regroup or to retreat – they were good at pillaging the countryside, thereby helping feed the army, and the smoke of villages they set afire might confuse the enemy as to where the main strength of the royal host lay.

The size of Jagiełło’s and Vytautas’ armies must have created serious problems for the rear columns. By the time thousands of horses had ridden along the roads, the mud in low-lying places must have been positively liquid, making marching difficult and pulling carts almost impossible; moreover, the larger any body of men and the more exhausted they became the more likely they were to give in to inexplicable panic. Scouting reports were unreliable; there were too many woods, streams, and enemy patrols. Nevertheless, the king, no matter how exhausted, nervous, or unsure he and his military advisors might be, had to avoid giving any impression of indecisiveness or fear; he had to appear calm at all times. Jagiełło’s dour personality lent itself to this role. A non-drinker, he was sober at all times, and his demeanour was that of total self-control. His love of hunting had prepared him well for the hours on horseback and feeling at home in the deepest woods; he would have regarded the lightly inhabited forests of Dobrin and Płock as tame stuff indeed. Vytautas was the perfect foil; he was the energetic and inspirational leader who was everywhere at once, at home among warriors and disdainful of supposed hardships. No common soldier could complain that their commanders did not understand the warrior’s life or the dangers of the forest, or that they did not share the tribulations of life on the march.

This need to appear to be in command was itself a danger – any army on the march can be held up at a ford or a narrow place between lakes and swamps, even if no enemy is present. The commander has to give some order, any order, even if it’s only ‘sit down’, rather than seem to be unable to make a decision. Such circumstances, compounded by exhaustion, thirst, or anxiety, often resulted in hurriedly issued orders to attack or retreat that the men are unable to carry out effectively. In short, circumstances might limit the royal options to bad ones, and the perceived need for haste might cause the king to select the worst of those available. Jagiełło was certainly aware of all this, for he was an experienced campaigner. However, for many years his strength had lain in persuading his foes to retreat ahead of overwhelming numbers, or in besieging strongholds; his goal had always been to prepare the way for diplomacy. Now he was leading a gigantic army to a confrontation with a hitherto invincible foe, to fight, if the enemy commander so chose, a pitched battle in hostile territory.

Jagiełło seemed to have been checked at the Dzewa River before he could cross into Prussia. He was unwilling to attempt to force a crossing at the only nearby ford in the face of a strongly-entrenched enemy; he would not find it easy to move eastward and upstream – while the headwaters of the Dzewa presented no significant obstacle to his advance, the countryside there had once been thickly forested, and important remnants of the ancient wilderness still remained. Most importantly, although the Teutonic Knights had used the century of peace to establish many settlements in the rolling countryside, the roads connecting the villages were narrow and winding. There were too many hills and swamps for roads to proceed from point to point, and strangers could easily lose their sense of direction in the dense woods. The villagers were fleeing into fortified refuges or the forest. Although many of the inhabitants spoke Polish (immigrants not being subject to linguistic tests in those days), they were loyal to the Teutonic Order, and none wanted to fall into the hands of Vytautas’ flying squadrons – especially not the terrifying Tatars – which were trying to locate the defensive forces and find a way around them. Making peasants give information or serve as guides was part of warfare. Burning villages marked the progress of the scouting units. Though this could hardly have been seen easily by the two armies confronting one another at the ford, they might well have been aware of the rising columns of smoke.

However, terrorising the countryside, burning, and pillaging was a far cry from the battle tactics that the Poles had become accustomed to; the long era of peace had softened the sensibilities of these amateur warriors. Polish knights were soon complaining to Jagiełło about their allies’ behaviour – Tatars hauling women into their tents and then raping them repeatedly, killing peasants who spoke Polish, treating captives inhumanely – until the king finally ordered the prisoners released and admonished the steppe horsemen to avoid such cruel practices in the future. This restraint was not in his best interests – the king’s best hope for making Jungingen weaken his position was to wreak such destruction on nearby rural communities that the grand master would feel compelled to send troops to protect them. However, within a short time Jagiełło and Vytautas saw that Jungingen was too good a commander to disperse his forces at such a critical moment.

The king must have been frustrated, yet he was unwilling either to allow his campaign to end from empty bellies or send his men to be slaughtered on some obscure river bank. While it was not clear that he could move eastward through the woods and swamps and around the incredibly complicated system of lakes without being easily blocked by the grand master, then forced to fight at a disadvantage, that seemed his only hope. This was, after all, the grand master’s home ground, and surely the Teutonic Knights would have seen to the building of some roads. If so, however, why were they not using them now to harass the Polish rear?

Jungingen, for his part, does not seem to have worried about a Polish flanking manoeuvre. Teutonic Knights from nearby convents had hunted for recreation in these woods; hence they were familiar with every village, field, and forest; they knew well how the many long, narrow, twisting lakes would limit the options available to invading armies. Polish and Lithuanian scouts had been active for days, looking for paths through the surrounding woods, and they had yet to find one. The assurance of such local residents as had undoubtedly agreed to act as guides and scouts for the Teutonic Knights, that the roads were not suitable for the use of any large army, may have given Jungingen more confidence in his superior strategic position than was warranted.

This confidence was misplaced, however. When the Lithuanian scouts reported that they had found some roads leading toward Osterode that could be used – if the army moved before the Germans learned what was planned – the king and grand prince acted on the information quickly.

Jagiełło consulted with his inner council, then gave orders to prepare for a secret, swift march eastward and north around Jungingen’s fortified position. He assigned each unit its place in the order of march and instructed everyone to obey the two guides who knew the country. The royal trumpeter would give the signals in the morning; until then no one was to make any movement or noise that might betray his plans prematurely. Unless his army could get a start of many hours, the stratagem was hopeless. Meanwhile, he sent a herald to make another effort at a peaceful settlement of the matter. Quite likely this was a deceptive manoeuvre to persuade the grand master that the king was in a desperate situation, but it might also have been a pro forma means of persuading the peace commissioners that he was truly desirous of ending the war without further bloodshed. It is hard to imagine what terms Jungingen might have considered acceptable in this situation, but the grand master nevertheless called a meeting of his officers; with one exception, they preferred war to further negotiations.

Jagiełło’s actions may well have increased the grand master’s overconfidence in the superiority of his situation. Certainly, when Jungingen’s scouts saw the Polish camp empty, they assumed that the king was withdrawing. The Germans crossed the river on swiftly erected pontoon bridges and set out in pursuit, knowing that there is nothing easier to destroy than an army on the retreat. However, when the scouts saw that the Poles and Lithuanians were moving north-east in two columns, working their way in a wide arc around their flank, Jungingen had to reconsider his plans. If his men continued following the enemy units, they would not be able to stop Vytautas’ Tatars from torching countless villages; worse, they might find themselves trailing the enemy through deep forests or fall into an ambush at some ford with nothing but desolated lands and wilderness at their rear. Therefore the grand master changed the direction of his advance in order to get ahead of the enemy columns. In fact the speed at which Jungingen’s army moved almost caused it to overshoot the Polish and Lithuanian line of march. Meanwhile, the Polish scouts had completely lost contact with the Germans and were surprised when they found Jungingen once again blocking the roads north.

Jagiełło, in luring the German forces east, away from their strong fortresses in Culm, was moving his own army far from safe refuges, too; moreover, he had divided his forces, sending the Lithuanians east and north of the road used by the Poles. Should the grand master somehow attack his forces by surprise, especially before they could reunite, Jagiełło might suffer an irreversible disaster. Because many Poles still considered him a Lithuanian under the skin, Jagiełło was placing his crown at risk in seeking battle under such conditions. This was something that Ulrich von Jungingen surely understood – a victory over the Polish and Lithuanian armies could ruin his order’s ancient enemies now and forever.