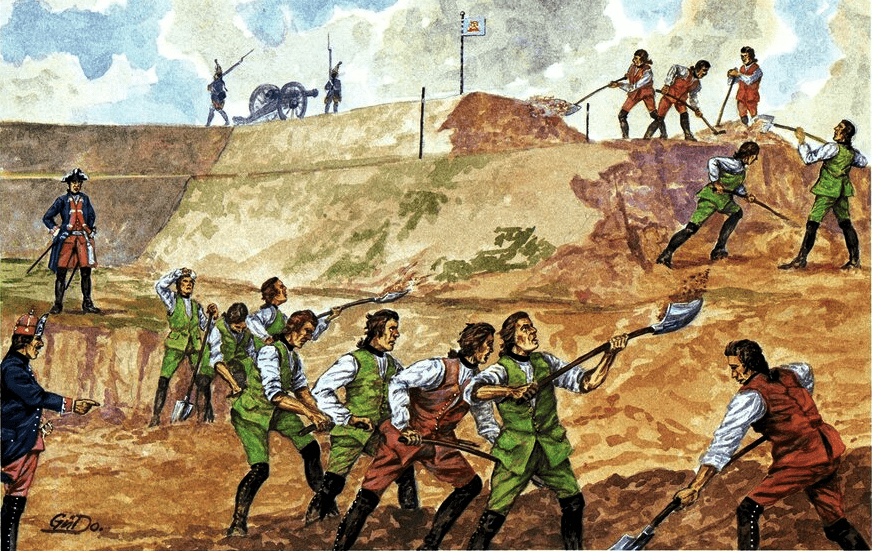

At Colberg 1761, the Swedish and Russian enemy’s interminable delay had given the defenders time to prepare their positions. Eugene of Württemberg had erected great entrenchments between the fortress and the enemy, now distant only some eight miles from Colberg. The defenders had also constructed a second wall round the first, but, although the landward defenses were being capably handled, the approaches from the seaside had been curiously neglected to a large degree. This is rather odd, as the Swedish and Russian fleets had controlled the Baltic ever since the defeat of the little Prussian squadron in 1759. And so it went.

Lt.-Gen. Peter Rumyantsev’s Russian force encountered a small Prussian force over by Belgard under cover of the darkness of June 14–15. A short attack was met by a blistering fire from the bluecoats, who were not prone to leave their post. The Russians fell back, but the timely arrival of reinforcements caused the attackers to be unleashed a second and then a third time. Over the course of the surprisingly vigorous little skirmish, the Russian force gradually built-up to over 700 strong.

This detail finally muscled the bluecoats back, and Rumyantsev’s progress continued. The first inkling Eugene of Württemberg had of the newly arriving Russian force was at the village of Varckmin, where one of his outposts was surprised and overwhelmed by a force of Russian Cossacks.

Rumyantsev’s force gradually linked up with the established detachment of Totleben. This rendezvous immediately formed a formidable core of greencoats in Eastern Pomerania. This body most directly threatened the bluecoat hold on Colberg. Rumyantsev promptly forwarded a note to General Jacob Albrecht von Langtinghausen, with the Swedes over in Western Pomerania, which suggested that the Swedes and the Russians should work together with a united purpose. A nice concept, indeed. Nothing came out of this, though, for Langtinghausen accountably declined to lend any assistance to the greencoats. There is no doubt this was due to the various flaws under which the Swedish army during this period always operated in the field: weak provision arrangements; poor supplies; no engineering and/or bridging equipment, etc.

Rumyantsev’s position was still further complicated, almost compromised, by the treachery of Colonel Gottlob Heinrich Friedrich Totleben, which was finally betrayed to the general light of day through a courier of the latter’s, Sabatko. Totleben was ordered home, and Buturlin dispatched some reinforcements from camps at Posen to help strengthen Rumyantsev with as much brevity as possible. The newcomers totaled a little over 4,000 strong, under General Nieviadomskii. The overall quality of this latter force was only marginal for the most part, but joining all of the Russian forces in the region together did provide a potent strike force to wield in the name of the Empress, nearly 18,000 strong.

Still, Rumyantsev did not deign proceed with a siege of Colberg itself until he had the support of the naval forces. This in the form of a powerful little Russian fleet, under the charge of Admiral Polanski, hailing out of Danzig (July 11–12). The ensemble numbered 23 warships and 44 transport/support ships carrying nearly 8,000 men, 42 guns, and ample stores of provisions of all kinds. The Russians were making their best effort to seize Colberg from its Prussian garrison. This included making sure that Rumyantsev’s men had everything they required to seize Colberg from the foe.

Polanski put his cargo and passengers ashore at and about Rügenwalde at the end of July, and the section of men brought by water advanced to form a juncture with Rumyantsev’s soldiers; which had, of course, advanced themselves by land.

August 17, six Russian ships-of-war arrived off the port, three had moved in towards Colberg and shelled some of the men working outside of the fortress on the entrenchments, with no more than nil success. But one thing was clear: the seaward approaches were now open to the Allied fleets. By August 24, the two allies had an impressive 54 ships anchored offshore, 42 of these being frigates, the rest Sail-of-the-Line. That evening a bombardment was commenced against the Prussian works from the ships’ batteries and the long-range land guns of Rumyantsev. It was an awesome display of power all right (for the total number of shells spent numbered over 3,000), but in truth the damage actually inflicted was likely minimal at best, and certainly nowhere near commensurate with the effort expended. A prolonged effort did serve to keep the garrison always on the alert and thus off-balance around the clock. So there was a psychological aspect to it all.

Meanwhile, Rumyantsev began creeping closer against the enemy works. August 18, after a questionable degree of preparation, Rumyantsev’s men, divided into two separate formations to expedite movement, pressed from Nosowko and Massow towards the enemy lines over near Colberg. Colonel Drewitz and his dragoons pointed the way in this latest endeavor. Colonel Bibkoff, at the moment, rolled towards Wyganowoff, while, at the van of the second column, Colonel Gruzdavtsiev moved on Körlin. Prussian resistance to this enterprise was spotty at best, so the greencoats were able to wrestle Körlin and Belgard away from their foe by August 19. Two days after, Russian spotters made it to Degow. Prussian resistance to the intruders gradually stiffened at this point, and the Russians, while pausing for a moment or two at Stockau, now resolved to put Colberg under yet another siege.

Rumyantsev was nonplused; by September 4, he had Eugene’s entrenched encampment under siege and was starting to shell Colberg from big ordnance on his end of the line. On September 5, shelling very early in the morning commenced. A total of “236 shells were lobbed at Colberg; 62 [of which] landed and exploded there.” About September 11, word filtered through to the garrison that Bevern (from Stettin) had gathered a force to move to Colberg’s relief and that this formation was already on its way. Learning that the newcomers were scheduled to be at Treptow on September 13, preparations were put in place to meet them. The Duke of Württemberg decided to send one of his best to the rescue, Werner with his 6th Hussars—one of the largest cavalry units, boasting 1,500 men and 120 non-commissioned officers. Under cover of the night of September 11–12, Werner pressed a small force towards Treptow. The last time that Werner had been unleashed against the rear of the Russian army, during the previous year’s campaign, he had brought their siege of Colberg to utter ruin. For a time, it looked like he might be able to do a repeat performance. But only for a while this go round.

Once joined with the new arrivals, Werner planned to attack one of Rumyantsev’s entrenched works—which had been prepared on that side of the line. On September 12, his Prussians reached Treptow, but unfortunately the enemy were waiting for Werner; at dawn, his men were suddenly attacked by the Russians as they were decamping. The bluecoats made a good show of the matter, but Werner was captured while leading a charge in which his horse was shot from under him. However, with the greencoats “distracted” by Werner, the incoming convoy and reinforcements got rerouted and so successfully—and belatedly—reached Colberg. But the loss of Werner was still a serious blow to his country.

In the meantime, Swedish General Stackelberg and his force, deployed about Neubrandenburg, had outposts in close proximity to the bluecoats of Belling. Prussian scouts overran the forward posts, very early on August 22. This served to alert the Swedes of the nearness of Belling’s men. The Swedish Plathen now embarked upon a timely attack which pressed against Belling. Initially, the Prussian horse thereabouts faltered, but this actually proved to be more of a trap than anything else. In the event, a prolonged advance by the onrushing cavalry came crashing to an abrupt halt when they met a solid wall of prepared Prussian infantry, backed up by gunners with well-sited batteries. The resulting effect was immediate.

As the combined fire of the bluecoat infantry and artillery shredded the formation of the startled Swedish riders, the reformed Prussian hussars slammed into the by now wavering enemy cavalry, sending them reeling. It was over in mere minutes. For some 50 casualties, Belling had cost the enemy some 300 casualties and inflicted yet another severe check upon the Swedish designs for a prolonged offensive.

With the threat of a Swedish advance temporarily nullified, Belling withdrew on Woldekg, while Ehrensvard continued a program to slowly build up his forces on the Northern Front to make any renewed offensive effort more viable. Meanwhile, having been reinforced from Stettin, Belling descended again upon Neubrandenburg (August 28), but found it evacuated by the enemy. Next, pursuing Stackelberg, the Prussians moved on Treptow, but the Swedes were too well dug in to attack thereabouts.

Belling, with his options basically reduced to one until he could receive reinforcements, withdrew posthaste to Teetzleben (August 29), but the arrival of the new formations of Stutterheim, getting to the scene of action on September 1, fundamentally shifted the bluecoats over into launching a counteroffensive against Ehrensvard’s forces. This effectively surrendered the initiative to the Prussians for the balance of the main campaign.

The Russians, for their part, were not prepared to let up before Colberg. Encouraged by the success of his force in capturing Werner, Rumyantsev on September 19 suddenly attacked the most accessible of the Prussian works (known as the Green Redoubt) about 0200 hours. The surprise stroke was at first successful, the Russians carrying the redoubt initially, but a determined counterattack at length repelled the intruders with the loss of 3,000 men of all arms, including some 800 dead. The Prussians lost 71 dead, 281 wounded, and 187 prisoners. This repulse induced the Russians to give up trying to take Colberg by a direct assault. Events beyond Colberg impacted the proceedings. After the adventure at Gotsyn, General Platen had detached Thadden to take the captured booty and the prisoners, not to mention the wounded, back to the Prussian lines.

Platen had unbuckled the busy Ruesch Hussars to proceed as quickly as possible to Posen, under the charge of Colonel von Naczimsky, to overturn the Russian supply arrangements thereabouts as completely as possible. The enemy reaction had been low key, although a Russian force under Major-General Gustav Berg was alerted to the possible arrival of Platen’s force hard about Driesen. When that scenario failed to materialize, Russian scouts probed for and finally located Platen’s men—between Neustadt and Landsberg (September 19). Berg sent a force of some 250 men under Suvarov to Landsberg (September 21). By this time, the bluecoats of Platen had ridden to Birnhaum and had even detected the movements of the enemy force towards Czerpowa. Platen finally entered Landsberg on September 22 with little fanfare, and, after a brief altercation with Suvarov’s men, and with no practical way to wreak further havoc upon the Russian supply lines, sped off for Colberg. Berg tried to launch a pursuit, but could not catch up with the wily Platen. Platen was able to throttle the enemy pursuit before he reached Arenswalde (September 26).

So, meanwhile, the defenders of Colberg received an unexpected, but timely, reinforcement. September 27, General Platen marched to join Eugene of Württemberg, raising Prussian strength to 15,000 men; although Buturlin similarly stiffened the besiegers with reinforcements (under the command of Dolgoruki), bringing them to 40,000 men. With the campaign in Silesia having gone sour again, Buturlin brought his main force to be in closer proximity to the fortress/port.

As soon as he reached the area, Buturlin reiterated the belief that Colberg could not be taken by direct assault, even though the task may have been manageable with the large influx of Russian troops in the vicinity occasioned by Buturlin. There was just no chance from a psychological perspective. With his army low on provisions and the expedition to Silesia a snub, the Russian commander turned about and, on November 2, headed for home.

It was a decision for which Buturlin would face tough scrutiny from an upset Elizabeth, who fired off a testy communiqué to the marshal. She and her court, upon receiving word of Buturlin’s backward hitch, wrote him “that the news of your retreat has caused us more sorrow than the loss of a battle would have done.” Elizabeth followed up, not mincing words, by ordering the marshal to march towards Berlin without delay and perforce levy a large contribution to help defray the campaign costs for the Russian army in this campaign, while, at the same time, seeking out an engagement with the enemy, should they threaten to intervene. As it turned out, Buturlin did not pounce upon the Prussian capital, but continued his progression back into Poland; basically ignoring the by now dying Empress. Rumyantsev was left with his force to finish the job before Colberg. An additional force of 15,000 Russians under Fermor was left to keep the roads from Stettin to Colberg closed and to prevent a repetition of the reinforcements just sent from Bevern at Stettin.

As for Platen, he continued to operate in the area beyond Colberg, riding into and decimating a Russian detachment at Cörlin (September 30), after which the Prussian commander made for Spie and Colberg. The enemy, not oblivious to his march, made a futile effort to bar Platen from the port, but the latter, yet again, was just too fast moving to be intercepted.

Frederick, far away near Strehlen in Silesia, ordered Bevern to prepare additional troops to be sent to the relief of Colberg. Could the blocked roads be opened, though? Prussian attempts to do just that read like an exercise in futility. October 13, “Green” Kleist and his dragoons tried to break through, but got repulsed. With this situation very bleak, the bluecoats forthwith dispatched Platen to try to bring some supplies in for Colberg.

General Platen had a full 42 squadrons of horse with just eight full battalions of infantry with him. He pressed off from Prettmin (about 0700 hours on October 17), with about 4,000 men. Prettmin was right near Spie, where General Knobloch was in charge of a small detachment. Platen, as was usual with the man’s character, made quick work of a march. His men rolled into Gollnow on October 18, and by the next day they were at Schwentdehagen.

Lt.-Col. Courbière was unleashed (October 20) with his force consisting of the Free Battalion Courbière, the Grenadier Battalion 28/32 of Arnhim, the III./ Belling Hussars, along with the apparently tireless Ruesch Hussars, and six pieces of ordnance, including one 7-pounder howitzer; a total of some 1,350 men. Courbière immediately proceeded with his mission. He was instructed to probe at the enemy positions in the immediate vicinity and to do all in his power to gather badly needed supplies for the hard-pressed garrison of Colberg. His men pushed across the Wolczenica River, and immediately occupied Zarnglaff.

The greencoats were close by in strength, over by Naugard, around 5,000 strong, including about 3,500 horse, led by General Berg. This generous allotment of cavalry allowed for a number of reconnaissance parties. It did not take long for the presence of Courbière’s Prussians to be discovered, and Berg drew up a scheme to deal with the intruders.

Early the next morning, the Russians pushed off, heading for a showdown in short order with Courbière. The latter sent off word to Platen that he needed some help against the much more numerous greencoats of Berg. The warning was correct, but it was far too late to send a rescue. The Russian wave advanced and in a very short fight, lasting less than 3/4 of an hour, compelled the bluecoats to lay down their arms, except for a small force of about 400 cavalry which did manage to wiggle free from the enemy’s grasp.

Platen, moving out from Colberg again, attempted in his own right to break up enemy concentrations from his side, while Kleist and General Thadden endeavored to do the same from the opposite end. Both attempts were unsuccessful. The Russians were making an effort to bag the whole of Platen’s corps. They were simply too inadequate to corner Platen. His troopers slipped past the greencoats through the Kautrek Forest, and rolled into Gollnow, despite their foe’s best efforts. Reinforced by a detachment under our old friend Fermor, Berg attacked and wrestled Gollnow from the unpleasantly startled Prussians. The bluecoats, nothing daunted, then marched, and countermarched, up and back the country roads and lanes north and northeast of Stettin, with no real chance to break through the enemy web by now encasing Colberg. These were the last undertakings at sending in supplies and reinforcements, and they were all abject failures, in spite of every well-intentioned goal having been made in advance, Eugene rose and, moving rapidly around and through the country between his lines and Rumyantsev’s, managed to evade the Russians by a series of skillful maneuvers.

The Russians, for their part, were making progress as well. Dolgoruki came rolling across the Persante (October 20), following which, his men occupied Gammin. Meanwhile, the Prussians were also settling in. Knobloch had pulled his forces back to consolidate at the vantage point of Treptow. While this was going on, Russian scouting parties laid hold of Przecmin and Sellno; at the latter, small bluecoat patrols in the area roamed around, while more significant bodies of Prussians were present just across the Persante.

The greencoat forces of General Brandt, deployed to Sellno to provide an anchor of sorts for their arms in that vicinity, could work in conjunction with Dolgoruki. Knobloch was left at Treptow, near where an enemy force appeared just after dusk on October 21, issuing from Gammin and vicinity. Prussian scouts calmly—and promptly—informed General Knobloch about the arrival of the Russian forces, and, nearly simultaneously, of the appearance of another greencoat detachment, hailing from Gabin. Before another 24 hours had elapsed, Rumyantsev himself was standing before Treptow, preparing, if necessary, to put the place and thus Knobloch’s command under siege.