The Royal Air Force (RAF) and Army Air Corps, based in Malaya, provided multi-role air support to emergency operations. This was either as an independent force of the operation, or in direct cooperation with forces on the ground. There were six facets to the availability of air support:

1.Photographic air reconnaissance facilitated informed planning and execution of anti-terrorist operations. An extensive air survey was conducted of the heavily populated areas, and active photographic tactical air cover made available. Light fixed-wing aircraft of the Army Air Corps were used for routine visual air reconnaissance, and had an active role target marking for RAF airstrikes.

2.Offensive air support was also multi-role. Due to restricted ground visibility from the air because of the very thick jungle canopy, the RAF had to rely heavily on pinpoint target coordinates from the ground forces for airstrikes to be effective. In the event of targets covering an extended area, but also dependent on target identification from the ground, bombers could lay down a deadly pattern to neutralise guerrillas positions. Often, an RAF representative would participate in the planning and implementation of ground operations in an advisory capacity when air support was included.

3.The supply of rations, ammunition and general supplies was essential to maintain sustained jungle operations. The terrain and general absence of a serviceable road network made the role of air supply critical for the success of prolonged counter-insurgency operations in the Malayan jungles.

4.For the same reasons, inaccessible areas of jungle required deployment of troops by air – light aircraft and medium helicopters. It also allowed for improved effectiveness as the troops could be deployed quicker and closer to the enemy.

5.Casualty evacuation by helicopter saved the lives of many a soldier wounded in action or suffering from some debilitating tropical disease. The medical exfiltration by this means enabled ground troops to continue with their operations, rather than having to evacuate a casualty by foot.

6.The dissemination of anti-Communist propaganda by air was also deemed useful, although problematic to quantify in absolute terms. Aerial leaflet drops or voice broadcasts formed an integral part of the psychological warfare during the emergency. As RAF planes continue to drop pamphlets throughout Malaya, Communists have intensified their propaganda warfare. Kluang police station in Johore yesterday received a bundle of Communist leaflets saying ‘Down with the British’ and promising ‘Death for the running dogs of the British’.

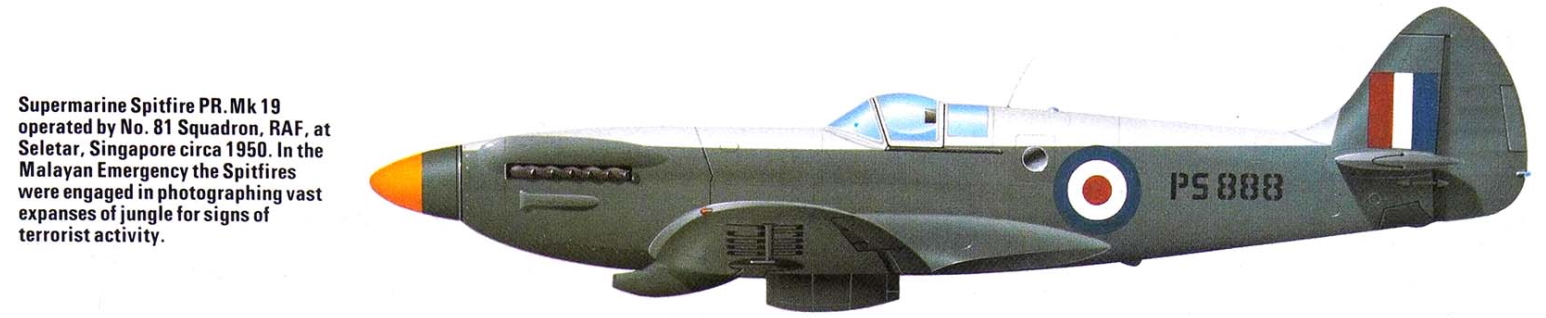

Around twenty squadrons from Britain’s Far East Air Force served during the emergency, flying English Electric Canberra bomber and reconnaissance aircraft, Spitfire FR-18s and -19s, Beaufighter TF-10s, de Havilland Mosquitos, Vampires and Venoms, Gloster Meteors, Percival Pembrokes, Scottish Aviation Pioneers, Taylorcraft Austers, Sunderlands Mk Vs (RAF Kai Tak, Hong Kong, and RAF Seletar, Singapore), Avro Lincolns, Westland Whirlwind helicopters, Bristol Sycamores, Douglas Dakotas, Vickers Valettas and Sikorsky helicopters.

The Royal Australian Air Force squadrons contributed Avro Lincoln heavy bombers (Butterworth air base), Canberra bombers, Dakota transports and CAC Sabre jet fighters; and from the Royal New Zealand Air Force, Vampires, Venoms, Dakotas, Bristol Freighters and Canberras.

Ships from the Royal Navy, such as HMS Amethyst, Comus, Defender, Hart, Newcastle and Newfoundland, conducted coastal anti-smuggling and anti-piracy operations, and were used for amphibious landings into inaccessible areas near the coast. Naval vessels also provided bombardment of targeted CT areas.

Naval support also came from Australia – destroyers Warramunga and Arunta, aircraft carriers Melbourne and Sydney, and Commonwealth Strategic Reserve forces destroyers Anzac, Quadrant, Queenborough, Quiberon, Quickmatch, Tobruk, Vampire, Vendetta and Voyager. The Royal New Zealand Navy’s frigate, HMNZS Pukaki complemented coastal patrols.

BRITISH TROOPS FIGHT BANDITS IN MALAYA

Troops of the Dorsetshire Regiment using machine guns today aided Malayan police in a dawn action against Chinese gangsters. The Chinese had attacked police at Nyor village, five miles from Lluang, in Jahore State. Two gangsters were killed and five wounded. A British sergeant was injured by a hand grenade.

(Dundee Evening Telegraph, Thursday, 25 September 1947)

This brief, four-sentence report was easily missed in many newspapers in the UK. As much space was given in the British press to a report from American General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters, which stated that the wartime Pacific commander had ordered the return to Singapore’s museum of 185 stuffed birds that the Japanese had pilfered during their occupation of Malaya for presentation to Emperor Hirohito.

The following month, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, together with extreme left-wing parties, called for a hartal – a general strike and closure of shops – in protest against plans by London to replace the unpopular Malayan Union with a federation of all the Malay states and Straits Settlements, but excluding Singapore.

Unperturbed, it was Britain’s wish that ‘internal self-government’ be returned to the Malayan Peninsula, apart from the Crown Colony of Singapore. On 21 January 1948, Britain signed agreements in Kuala Lumpur with the rulers of nine Malayan states, thereby paving the way for a ‘Federation of Malaya’. The new state would be promulgated by the issue of an Order in Council from Governor Sir Edward Gent in February. Gent would then become High Commissioner, while resident British commissioners in each of the federal states would only have advisory powers.

The latest British initiative merely served to harden Malayan Communist Chinese resolve to expedite their quest for a people’s republic encompassing the whole peninsula.

While the wartime marriage of convenience between the British and the MCP’s military wing, MPAJA, was a tactical necessity to rid Malaya of the Japanese, the MCP was already planning its strategies to also oust the British. A covert programme of Communist indoctrination by means of propaganda was conducted to sensitise the ‘masses’ to the need for resistance.

The MCP, however, could not anticipate the militarily strong British administration that took over from the Japanese, effectively stalling the timing of their revolution. While ensuring that they were seen by the British to be cooperative subjects of the Crown, the MCP took its subversive activities underground. In line with Mao’s teachings, MCP activists infiltrated government and public departments, such as schooling and local government councils.

In the first quarter of 1948, the MCP started to implement by deed their doctrinal objectives. Initially, this took the form of nationwide civil disorder, exploiting the legitimacy of their actions in terms of the federal government’ s Trade Union Ordinance.

By this time, the MCP had divided its strategies into two – the Jungle Organisation and the Open Organisation. Whilst the federal authorities, ‘assisted’ by the British, were unable to legitimately classify the overt trade union activities as acts of terrorism, the Open Organisation played a fundamental role in the Communist insurrection.

The Jungle Organisation itself comprised two elements – the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA) and the Min Yuen, or Mass People’s Movement.

Initially comprised of regiments, logistical necessities made the structure difficult to manage, so independent platoons were created instead. With platoon strengths fluctuating between fifteen and thirty, the units came under the command of a state committee member (SCM), which allowed for areas of operation to overlap. Local militia, referred to as the Armed Work Force, augmented platoon ranks.

About 90 per cent of the communist terrorists were ethnic Chinese, the balance mainly Malay and Indian, with one or two Siamese, Japanese and Javanese. Generally young, the Communist Terrorists (CTs) were jungle habituated, attuned to the lay of the land in which they operated. Hardened survivalists, they understood deprivation and the necessity of living off the jungle. Their fieldcraft and tracking skills were, for the majority, second nature in the familiar environment.

Much of the CTs’ war materiel, unearthed from Second World War jungle caches, was of diminished quality. Compounded by the metal-unfriendly jungle conditions, British military analysts rated CT handling and maintenance of arms and ammunition as ‘adequate for the type of warfare they are engaged in’. Questionable weapons’ serviceability impacted on the morale of the guerrillas. This, together with the efficacy of the British and Commonwealth security forces, food supply, quality of leadership and strength of conviction to the cause, meant for CT tactics that were largely hit-and-run in execution. Only the most zealous adherents to the Communist dogma would show determined resistance in combat.

The CTs drew from cached British and American stock weaponry issued to the anti-Japanese guerrillas during the occupation. Weapons included .303-calibre Bren light machine guns, 9mm Sten sub-machine guns, Thompson .45-calibre ‘Chicago Organ Grinder’ sub-machine guns, American .30 semi-automatic carbines, British .303 SMLE rifles, 12-bore shotguns, Russian-made Tokarev TT-33 pistols, and dated British revolvers.

A Ho Lung CT camp in the Sungei Palong area, southern Malaya.

CT campsites were meticulously selected, with an emphasis placed on unlikely positions to the casual observer, and a reliable source of clean water. The larger, more permanent camps had bashas constructed from natural materials found in the area, a parade ground and an outdoor lecture facility. Some camps had rudimentary armouries for basic weapons repair.

Two-way radio communications were rare, the CTs lacking suitable equipment. Two- or three-man courier groups were the norm in jungle operational areas, which included the conveyance of printed Communist propaganda. So-called open couriers proved the most effective and expedient means of communication, and one that the local law enforcement agencies found extremely difficult to detect, let alone eliminate. Invariably, these open couriers were readily available Min Yuen, blending in with the general populace as an ordinary citizen going about their daily routines.

Instructional material in guerrilla tactics such as vehicle and security force ambushes, defensive positions, reconnaissance and use of weapons, was sourced from translations of Russian and British manuals, and leaflets of the Chinese People’s Army sent in from China.

The Malayan civil government was, in the first instance, the responsible authority for the anti-terrorist campaign. Viewed at first as a civil action, CT attacks on civilians were regarded as of a criminal nature, and therefore a matter for the police force to address. With the escalation in acts of terrorism, armed forces – local, British and Commonwealth – were brought in to support the civil authorities. A home guard was also formed, mainly to release combatant troops from urban and village defence duties.

By 1950, the coordinated responsibility for the control of all counter-terrorist operations lay with the Emergency Operations Council – EOC. Answerable in turn to the federal government of Malaya, the EOC was tasked with the use of fully integrated civil and military resources to totally eradicate the Communist terrorists.

Chaired by the prime minister, the EOC comprised government ministers, the commissioner of police, the flag officer (navy) of the Malayan area, the general officer commanding overseas Commonwealth land forces, the air officer commanding No. 224 Group, RAF, and the deputy secretary, security and intelligence in the prime minister’s office.

Responsible for the day-to-day conduct of emergency operations, the Federal Director of Emergency Operations was a senior British army officer seconded to the Federation of Malaya government. Generally referred to as the Director of Operations, this officer chaired the Commanders’ Sub-committee, made up of the commanders of the army, air force, navy and police in Malaya. These combined forces’ operational structures were replicated at state and district levels, in descending chain of command.

The job of the security forces was threefold:

1.The strict control of concentrations of the civilian population, in cities, towns, kampongs (villages) and plantation lines. The forces had to be in a position to not only defend civilians from CT intimidation and brutality, but also to prevent supplies of food being smuggled out to the CTs by Communist sympathisers.

2.To perform offensive operations in areas surrounding centres of population, with the objective of cutting the flow of food by eliminating the CTs.

3.To mount deep-jungle, seek-and-destroy missions to isolate them from the local populace and to destroy camps, food and arms caches, and lands cultivated for food production.

Severing the link between CT and civilian was deemed key, and therefore warranting a systematic programme of isolation of one from the other. This process became a reality with the controversial introduction of the Briggs Plan.