The fully armoured cataphracts were mounted on horses whose head, neck, chest and sides were similarly protected by metal armour and the army’s strength lay in the combination of these troops with the light horse archers. The least successful Parthia armies were those using the most cataphracts and the fewest horse archers. The cataphract camels used in 217 AD were probably Hatrene. Foot were only used in defending cities or in the mountains. A Sassanid triumphal sculpture shows the defeat in 224 AD of Parthian dignitaries who are fully armoured in cataphract style, but mounted on apparently unarmoured horses, but close examination shows that horse armour is in fact depicted. Sarmatian allies were hired for an intervention in Armenia in 35 AD, though they failed to link up. A large force of other allies did join and may have been Dahae, who also took part in a civil war from 39 AD to 41 AD. Armenians, mountain tribesmen, city troops.

Dio (2nd-3rd C. AD), 40. 14

(An account of the Parthian empire at the invasion of Crassus in 53 BC). They (the Parthians) finally rose to such a pitch of distinction and power that they actually made war on the Romans at that time, and from then onwards down to the present day were considered comparable to them. They are indeed formidable in warfare, yet their reputation is greater than their achievements, since, although they have never taken anything from the Romans and have moreover surrendered certain parts of their own territory, they have never been completely conquered, but even now are a match for us in their wars against us when they become involved in them. (There follows a description of the Parthian army and the climatic conditions). For this reason they do not campaign anywhere during this season (winter, when the damp weather affected their bowstrings). For the rest of the year, however, they are very difficult to fight against in their own land and in any area that resembles it. For they can endure the blazing heat of the sun because of their long experience of it, and they have found many remedies for the shortage of water and the difficulty of finding it, with the result that they can easily drive away anyone who invades their land. Outside this land, beyond the Euphrates, they have now and again won some success in battles and sudden raids, but they cannot wage a continuous, long-term war with any people, both because they face completely different conditions of climate and terrain, and because they do not prepare a supply of provisions or money.

This is about the only detailed, rational analysis we have of a power on the periphery of the Roman empire that might be perceived as a threat. Dio is probably expressing a late-second century view based on the accumulated wisdom of Roman experiences in the east. Note also his comments (80. 3) on the rise of the Persians, who around AD 224 replaced the Parthians as the dominant force east of the Euphrates.

The backbone of the Parthian army was the cavalry. For the Parthians, who, as former inhabitants of the steppes, had lived a life of transhumance, horses were an essential part of their way of life. Their Persian predecessors, the Achaemenids, were renowned for their Nisaean horses, which were bred in Media. In the Parthian period, the region of Ferghana on the Jaxartes River became renowned as a further centre for horse-breeding. Horseback was also the most effective way of covering, in war, the vast distances of the Parthian territory, which featured high mountains and vast plateaux. The plains provided an ideal terrain for battle.

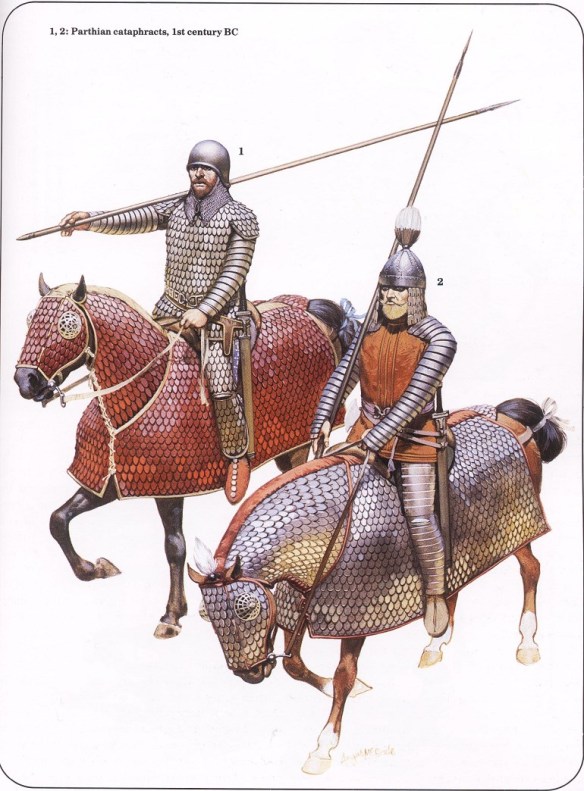

The strongest cavalry force was the cataphracts (probably identical with the later clibanarii). The cataphracts wore fully mailed armour, and their horses were protected by a blanket of chain mail. As weapons the rider carried a lance, bows and arrows. They were equipped for a full frontal attack on the enemy lines.

The lighter cavalry was also equipped with the composite bow and arrows, but their clothing only consisted of a belted tunic and wide trousers and boots. Their relatively light clothing allowed a freedom of movement needed in an attack, for their task was to deceive the enemy and encourage him to break his ranks. To do that, they attacked and then seemingly retreated from battle, giving the enemy soldiers a false sense of security which made them pursue their attackers, only for the Parthians to turn backwards on their apparently fleeing horses and shoot their arrows in mid-gallop.

Infantry, consisting of soldiers and mercenaries, was only employed after a cavalry attack had broken up the enemy lines, and battle was continued on the ground. The infantry probably included peasants who were obliged to do military service, as well as mercenaries and special forces like the Scythians. The fact that the Parthian army was not a standing army had no bearing on the Parthians’ ability to muster an army quickly and efficiently. Forces were recruited as close to a military conflict as possible, and reinforcements would be brought in on demand.

The organization of the Parthian army is not clear, and lacking a standing force, a strict and complicated organization was unnecessary in any case. The small company was called washt; a large unit was drafsh, and a division evidently a gund. The strength of a drafsh was 1,000 men, and that of a corps 10,000 (cf. Suren’s army). It seems, therefore, that a decimal grade was observed in the organization of the army.

The whole spad was under a supreme commander (the King of Kings, his son, or a spadpat, chosen from the great noble families). The largest army the Parthians organized was that brought against Mark Antony (50,000). At Carrhae the proportion of the lancers to the light horse was about one to ten, but in the first and second centuries the number and importance of the lancers as the major actors of the battle-field increased substantially. The Parthians carried various banners, often ornamented with the figures of dragons, but the famous national emblem of Iran, the Drafsh-e Kavian, appears to have served as the imperial banner. The Iranians marched swiftly but very seldom at dark. They used no war chariots, and confined the use of the wagon to transporting females accompanying commanders on expeditions.

The Parthian period holds an important place in military history. Several Parthian King of Kings, including the first and the last-fell in action, and their three century long conflicts with Rome had profound effects on Roman military organization. For they not only succeeded in repulsing repeated Roman attempts at the conquest of Iran, but they inflicted severe defeat seven in their last days-upon the Roman invaders; and to face the long-range fighting tactics of the Parthian armoured cavalry and mounted archers, the Romans started to supplement their armies of heavy and drilled infantry with auxiliary forces of riders and bowmen, thereby increasingly modifying traditional Roman arms and tactics. The Parthians finally submitted to another Iranian dynasty which had close links with them and retained the power of their nobility, one reason for their defeat being that while they still wore the old style lamellar armour, the Sasanians went to battle with the Roman type mail shirt, i.e., armour of chain links, which was more flexible and afforded better protection.