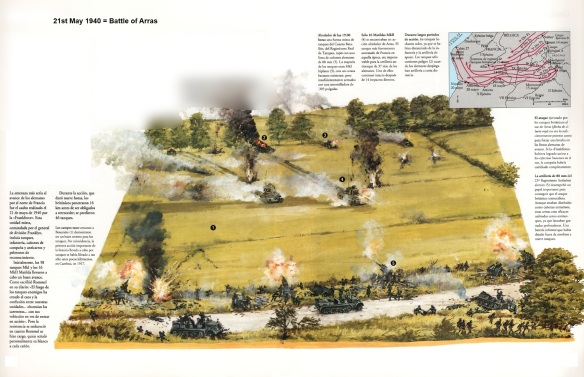

By the evening of 20 May, Guderian’s panzer spearheads had reached Abbeville at the mouth of the Somme, and at this point their line was as thinned out as it ever would be. The Germans were vulnerable to a determined counterattack, but the only one that threatened the speeding panzers was by British tanks at Arras on 21 May. The Allies inflicted a stinging reverse on the SS Totenkopf division, but they quickly found themselves blocked by Rommel’s panzers. After a brisk battle, the British were driven back to their original positions and threatened with encirclement.

#

On the main front, there was a glimmer of hope. Georges, despite his pessimism, tried to organize a counterattack and positive results came from the advance of the 1st DLM and 1st North African Division in the Mormal Forest where the 5th Panzer Division was engaged. The DLM’s SOMU As discovered a number of abandoned Char B tanks, but were unable to establish contact with headquarters to recover these valuable vehicles. Throughout the rest of the campaign, the Germans continued to find a good number of abandoned French tanks which were unserviceable or simply had run out of fuel.

Prime Minister Paul Reynaud was meanwhile forced to make changes in his command. He finally decided to replace Gamelin with General Maxime Weygand who returned from Syria on 18 May, as Gamelin was trying to seal the German penetration. Meanwhile the Prime Minister was also faced with reorganization of his cabinet. He called on the old war hero Marshal Philippe Pétain to serve in his government and hopefully restore confidence. Nothing, however, could avert disaster. The Belgian king, ready to give up, withdrew his army to the last corner of his kingdom. British concern regarding the fate of the BEF and its survival intensified. By 19 May, the Germans were already establishing bridgeheads over the Somme River which was rapidly becoming untenable as a defense line for the French. The problem facing the French High Command was how to defend the ever-expanding front when already up to one third of its forces, including allies, were destroyed or trapped in the North.

Gamelin hoped to take advantage of the vulnerability of the German spearhead and send his troops against its shoulders which would disrupt the lines of communication behind the panzer units. He ordered the 2nd Army to launch an offensive action in the vicinity of Sedan, and commanded the units of the main body of the 1st Army Group to attack further southwards towards Cambrai. Before the preparations for these actions could be effected, Gamelin was replaced by Weygand on 20 May who decided to make his own evaluation of the fluid situation before going on the offensive. The French, now as ready as they could be, lost more time awaiting the decision of the new commander.

The day of 19 May only brought a few encouraging moments for the Allies as the overall situation of the 1st Army Group deteriorated. De Gaulle’s 4th DCR, now comprising about 150 tanks, struck again at the Germans, and this time hit Guderian’s left rear in the vicinity of Laon. Mines, anti-tank guns and Panzer IVs finally brought de Gaulle’s armor to a halt at Crécy (not the town where the French were defeated during the Hundred Years War). As on 17 May, the French division was hard hit again by the Luftwaffe. In a tragic error, the Armée de l’Air assigned to protect them didn’t show up until after the Stukas had turned back the French tanks because of a change in the scheduling. Though Guderian later claimed the action had given him some uncomfortable hours, the beaten attack was not hardly enough to stem the almost irresistible tide. The whole incident did demonstrate though just how effective French armored units might have been if only they had had a more adequate divisional organization and better coordination between units. Afterwards, the French Cavalry Corps attempted to reorganize its DLMs.

Despite the Allies’ best efforts, the Germans breached the line of the Escaut River adding to the difficulties of the encircled 1st Army Group. To make matters worse, the French abandoned the remaining three ouvrages of the Maginot Extension, fearing that these forts might suffer the same fate as La Ferté since they had not been designed to be defended in the same way as the Maginot Line Proper. As a result, the Germans firmly secured their flank at Sedan. To add to the woes of the French, both General Giraud, commanding the 9th Army, and General Bruneau, who had fought with his 1st DCR to the end, fell into German hands.

In a renewed offensive on 20 May, Guderian’s corps, in conjunction with Reinhardt’s and Hoth’s, overran the British 12th and 23rd Territorial Divisions holding the line of the Canal du Nord. General Gort had requested and received these two poorly trained divisions late in April to use mainly as a labor force. General Ironside had directed him to make sure they received additional training, but he failed to do so. The German breakthrough forced Gort to move them into the line in order to block the German drive to the sea, a hapless move since neither unit was assigned the three artillery regiments or the anti-tank regiment that were the normal components of a British infantry division. Their infantry battalions were also poorly armed. Each had three rather ineffective Boys anti-tank rifles, with five rounds of ammunition each and even then few of the men were experienced to operate them. For the moment, these divisions represented the only forces available to bar the German thrust. The 2nd Panzer Division quickly cut through the British line and soon reached the coast at Abbeville, sealing the trap for the 1st Army Group and the BEF. Meanwhile, the French command ordered the British 5th and 50th Divisions with the 1st Army Tank Brigade to prepare for Gamelin’s earlier planned attack together with the remaining armor of the French Cavalry Corps. Since the British were not able to load their tanks onto trains, they had to drive them most of the way out of Belgium, which gave rise to numerous maintenance problems.

On 21 May Weygand finally decided to launch assaults from both sides of the German spearhead in hopes of cutting it off and relieving the encircled units of the 1st Army Group. In other words, he simply followed Gamelin’s strategy, after having delayed its implementation. At a conference held at Ypres, Weygand ordered Billotte to launch an attack towards the south, in the vicinity of Bapaume, with the forces he had available. A similar operation would be initiated with units on the Somme. Billotte’s limited resources included the remnant of his DLMs. His last remaining DCR had been eliminated as a fighting unit. General Besson, commanding the French 3rd Army Group on the Somme, was still building up his new front with the 6th and 7th Armies. He had the 3rd DCR, which had been rebuilt from training units and depots, and the 2nd DCR with less than half of its original equipment, but neither of these units was ready for an offensive move. Weygand’s new orders to attack pushed the date back to 26 May, causing a delay which could have been avoided by going ahead with Gamelin’s original plans. No attacks took place in the end, partly because French morale had been shattered by 25 May.

During the day of 21 May, as Guderian’s XIX Panzer Corps, after securing a bridgehead on the Somme, advanced on Boulogne and Calais, the British attempted to reinforce the motley French garrisons of those ports. The 20th Guards Brigade, consisting only of the 2nd Battalion Irish Guards, the 2nd Battalion Welsh Guards and an anti-tank battery arrived at Boulogne. It soon faced the 2nd Panzer Division. Another two battalions from the 30th Infantry Brigade, with the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Tank Regiment from the 1st Armored Division, a former motorcycle battalion and an anti-tank battery, completed the British force defending Calais. According to General Ironside, these were the last Regular Army troops left in England. Initially, Guderian sent the 1st Panzer Division against this force.

As Guderian’s panzers began to advance on the left wing of the German spearhead, the British began an offensive against Hoth’s panzer corps on the spearhead’s right flank. The weak British 1st Army Tank Brigade, with its 58 Mark I tanks armed only with machine-guns, and 16 of the slow but more formidable Mark II Matilda infantry tanks armed with 40mm guns, launched the only Allied attack of 21 May. The 3rd DLM, with its 60 SOMUA tanks, joined the British raid, advancing on their right flank as they moved south of Arras. Of the two British divisions assigned to this offensive, only two infantry battalions arrived. The Allied attack spread panic among the still green troops of the SS Totenkopf Division, convincing Rommel that his 7th Panzer Division was under attack by upwards of five divisions. The shaken general took personal control of the situation, throwing back the Allies at the battle of Arras. Rommel recounted that when his 6th Rifle Regiment failed to stop the British tanks with its anti-tank guns and began to take heavy losses, his divisional artillery intervened, bringing the attack to a stop and destroying 28 tanks. His 88mm anti-aircraft guns eliminated another seven light tanks and one heavy tank. Finally Rommel’s 25th Panzer Regiment joined in taking the British in the flank and rear. Seven more Matildas were knocked out for a corresponding loss of three Panzer IVs, six Panzer IIIs and a number of light tanks in the resulting tank battle. This action caused the Germans much greater concern than the 19 May attack of de Gaulle’s armored division, even though the latter could have inflicted more serious damage if it had succeeded in cutting off German supply lines.

On the evening of 21 May, after completing his conference at Ypres, Weygand found it impossible to return to his headquarters by air and had to take his leave from the isolated army group on a destroyer. Meanwhile, an automobile accident took Billotte’s life. This created further problems because his replacement, General Georges Blanchard, the commander of the 1st Army, lacked the authority and personality to direct the British and Belgian forces. Blanchard was unable to marshal the units needed for the planned offensive and his army group no longer had the needed mechanized units to stage an offensive, as many units had wasted away in piecemeal actions. The best the French could hope to achieve at this point was to maintain a defensive position. Since this would only be a temporary solution, the remnants of 1st Army Group were doomed.

Each day the situation grew worse. On 22 May, the French 1st Army’s V Corps began its own offensive. Instead of the required divisions, the V Corps mustered a single regiment with some armor support for the assault. The offensive thus degenerated into a raid in the direction of Cambrai. It achieved some success, reaching the outskirts of Cambrai only to be driven back by a superior German force. While it was again too little too late, the effort demonstrated that the French had the men and equipment for mechanized warfare, but lacked the proper leadership in the higher echelons.