Mercenaries have earned a dubious name for themselves throughout history; their object, as a rule, has been to obtain maximum pay for minimum risks, with the result that those hiring them rarely get value for money. Mercenaries, usually white and recruited from the former colonial powers, became familiar and generally despised figures in Africa during the post-independence period. They were attracted by the wars, whether civil or liberation, that occurred in much of Africa during this time and, as a rule, were to be found on the side of reaction: supporting Moise Tshombe in his attempt to take Katanga out of the Republic of the Congo (1960–63); in Rhodesia fighting on the side of the illegal Smith regime against the liberation movements; in Angola; on both sides in the civil war in Nigeria; and in other theaters as well.

The Congo

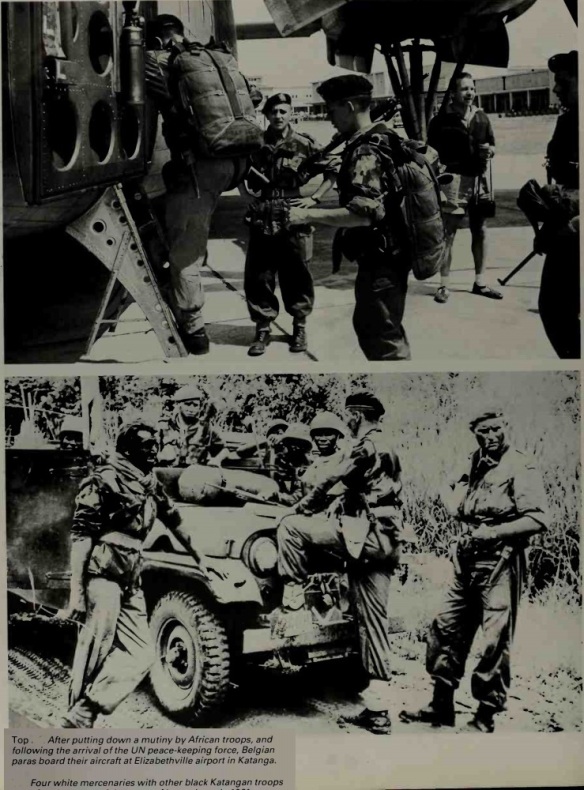

In the chaos of the Republic of the Congo (1960–66) mercenaries were labeled “les affreux.” In Katanga under Tshombe, they were first used to stiffen the local gendarmerie; later they were organized in battalions on their own, numbering one to six commandos, as a fighting force to maintain Tshombe’s secession. There were originally 400 European mercenaries in Katanga during the secession; this number rose to 1,500 during the Simba revolt, which affected much of the Congo. These mercenaries came from a range of backgrounds: British colonials, ex-Indian Army, combat experienced French soldiers from Algeria, World War II RAF pilots from Rhodesia and South Africa, and Belgian paratroopers. The troubles that began in the Congo immediately after independence in July 1960 provided the first opportunity for mercenaries to be employed as fighting units since World War II. These white soldiers fighting in black wars, both then and later, became conspicuous military/propaganda targets in an increasingly race conscious world.

Nigeria

The Nigerian civil war (1967–70) witnessed the use of white mercenaries on both sides, and stories of mercenary involvement and behavior were a feature of that war. Three kinds of mercenary were used: pilots on the federal side; pilots and soldiers on the Biafran side; and relief pilots employed by the humanitarian relief organizations assisting Biafra. Memories of savage mercenary actions in the Congo were still fresh in African minds when the Nigerian civil war began and at first, there was reluctance to use them. Despite a great deal of publicity, the mercenaries played a relatively minor role in the Nigerian civil war, except for air force pilots. French mercenaries led a Biafran force in a failed attempt of December 1967 to recapture Calabar. In Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa, the mercenaries were well aware of the low esteem attached to them and were careful not to put themselves at risk of capture. The Nigerian Federal Code (for the military conduct of the war) said of mercenaries: “They will not be spared: they are the worst enemies.” Although both sides in Nigeria were reluctant to use mercenaries, both did so in the end for what they saw as practical reasons, especially because of the shortage of Nigerian pilots. In this war, British mercenaries fought for the federal side against French mercenaries on the Biafran side to perpetuate existing Anglo–French rivalries in Africa; it was the first time since the Spanish civil war of 1936–1939 that contract mercenaries had faced each other on opposite sides.

Mike Hoare, who had become notorious as a mercenary in the Congo, offered his services to each side in Nigeria in turn, but neither wished to employ him. The capacity of Biafra to resist against huge odds was prolonged because Ulli Airport was kept open to the last moment in the war; had it been destroyed, Biafra would have collapsed, but the mercenaries on either side had engaged in a “pact” not to destroy the Ulli runway, since to do so would have put the pilots on both sides—those bringing in supplies to Biafra and those supposedly trying to stop them for the federal government—out of a job. At least some mercenaries in Biafra were involved in training ground forces and helping to lead them, and some of these became partisan for Biafra, though that is unusual. The French government supported the use of its mercenaries in Biafra, since it saw potential political advantage to itself if the largest Anglophone country on the continent should be splintered. Apart from the pilots, however, Biafra got small value for money from the mercenaries it employed.

Why Mercenaries Were Employed

As a rule, the mercenaries offered their services in terms of special skills—such as weapons instructors or pilots—that were in short supply among the African forces at war. The need for mercenaries in most African civil war situations has arisen from the lack of certain military skills among the combatants and the belief that mercenaries are equipped to supply these skills. What emerges repeatedly in the history of the mercenary in Africa—whether in Nigeria, Angola, or elsewhere—is the fact that mercenaries charged huge fees (to be paid in advance) for generally poor and sometimes nonexistent services. As a rule, they were simply not worth the money. The mercenaries always sought maximum financial returns and minimum risks and in Nigeria, for example, helped destroy the notion that white soldiers were of superior caliber to black ones. This was simply not true. Zambia’s President Kenneth Kaunda notably described mercenaries as “human vermin,” a view that had wide credence in Africa, so that their use by any African combatant group presented adverse political and propaganda risks. An assumption on the part of many mercenaries was that they were superior soldiers and would stiffen whichever side they were on; many, in fact, turned out to be psychopaths and racists whose first consideration, always, was money. In general, mercenary interventions in African wars were brutal, self-serving, and sometimes downright stupid and did more to give whites on the continent a bad name than they achieved in assisting those they had supposedly come to support. The desperate, that is the losing, side in a war, would be more likely to turn to mercenaries as a last resort, as happened in Angola during 1975–1976.

Angola

The mercenaries, who became involved in Angola during the chaos that developed as the Portuguese withdrew in 1975, appeared to have learned nothing from either the Congo or Nigeria. As the Frente Nacional da Libertação de Angola (FNLA)/National Front for the Liberation of Angola was being repulsed by the Movimento Popular para a Libertação de Angola (MPLA)/Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola and its Cuban allies, the American CIA decided to pay for mercenaries and proceeded to recruit 20 French and 300 Portuguese soldiers for an operation in support of the anti-Marxist FNLA. The CIA recruited French “hoods” for Angola and the French insisted that the CIA should use the services of the notorious Bob Denard. He had already worked for Joseph Désiré Mobutu in the Republic of the Congo. It was thought that French mercenaries in Angola would be more acceptable or less offensive than Portuguese mercenaries. Despite this, the Portuguese, having lost their colonial war, allowed and encouraged a mercenary program of their own in Angola, in opposition to the newly installed MPLA government. In fact, the use of mercenaries in Angola in 1975 proved a fiasco. By January 1976, for example, over 100 British mercenaries were fighting for the FNLA in northern Angola. They were joined by a small group of Americans.

One of the most notorious of these British mercenaries, a soldier by the name of Cullen, was captured by the MPLA and executed in Luanda. In February 1976, 13 mercenaries including Cullen were captured by MPLA forces in northern Angola: four were executed, one was sentenced to 30 years in prison, and the others got lesser though long terms of imprisonment.

Later Mercenary Interventions

In 1989, white mercenaries under the Frenchman Bob Denard seized power in the Comoros Islands following the murder of President Ahmad Abdallah. At the time, South Africa was paying mercenaries to act as a presidential guard in the Comoros. As the Mobutu regime in Zaire collapsed during the latter part of 1996 and 1997, senior French officers were recruiting a “white mercenary legion” to fight alongside Zaire’s government forces. In January 1997, it was reported that 12 or more French officers with a force of between 200 and 400 mercenaries—Angolans, Belgians, French, South Africans and Britons, Serbs and Croats—had arrived in Zaire. As Laurent Kabila’s forces advanced on Kisangani there was a mass exodus of the population, including the Forces Armées du Zaire (FAZ)/Armed Forces of Zaire troops of Mobutu and many of the mercenaries who had been recruited by the Zaire government. These latter then quit the country.

In summary, mercenaries in Africa, by their brutal behavior and racism, have done great damage to the white cause on the continent; they have proved less than able soldiers; they have often quit when their own lives were in danger rather than do the job for which they had been paid; and with one or two exceptions, the combatants would have been better off without using them.