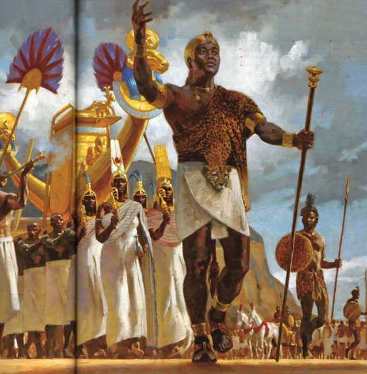

Piye (formerly known as Piankhy)

The Kingdom of Kush was Egypt’s powerful southern neighbor, located south of the Third Cataract of the Nile River in upper Nubia (present-day Sudan). The history of Kush spans more than 1,000 years (from approximately 1000 BCE to 350 CE) and is divided into two periods, the Napatan period (ca. 1000-310 BCE) and the Meroitic period (ca. 275 BCE-350 CE). Each period is sometimes called a dynasty, a kingdom, or an empire.

After the withdrawal of the ancient Egyptian administration, which had controlled most of Nubia during the New Kingdom (ca. 1540-1075 BCE), a local Nubian chiefdom emerged at the turn of the millennium. This new political power was centered at Napata, the city at the foot of the so-called Pure Mountain at Gebel Barkal near the Fourth Cataract. Very little is known of the formative years of the Kingdom of Kush. Archaeological evidence is scant and written documents nonexistent, because at the time the Nubians did not have a writing system of their own.

Around 785 BCE a local chief known as Alara united upper Nubia. He is acknowledged by later kings as the founder of the Napatan dynasty of Kush and is believed to be the one who restored the cult of the god Amun in Nubia at the sacred site of Gebel Barkal. The Kushites also adopted ancient Egyptian and the hieroglyphic writing system as the administrative and religious language of their kingdom. Kashta, Alara’s successor, united upper and lower Nubia into a single political entity, and he called himself “King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” as mentioned on his small stele at Elephantine.

However, it was Piye (formerly known as Piankhy) who actually conquered and took control of Egypt and annexed it to the Kingdom of Kush (747-716 BCE) during the third year of his reign. Piye founded the Kushite Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, and his successor Shabaka

(Shabaqo) established the capital at Memphis. The Kushite kings held sway over all of Egypt for almost a century, following traditions established by earlier Egyptian kings. In honor of the god who granted them kingship, they added new monuments to the architectural complex of the Temple of Amun at Karnak (Thebes), the religious center of this god in Egypt. The Kushites remained active in their homeland, erecting new temples to the god Amun and refurbishing ruined ones built by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom. The Kushite Twenty-fifth Dynasty was expelled from Egypt by the Assyrians, who sacked Thebes in 663 BCE. King Tawetamani had already taken refuge at Napata.

Most of what is known of the remainder of the Napatan period comes from Kushite royal documents, which were still written in Egyptian using hieroglyphs despite the fact that the Kushites had lost control over Egypt. These documents-stelae and wall inscriptions-come mostly from temples and royal burials and concern mostly the north of the kingdom. Very little else is known of this period, especially regarding the local general populace. Few village settlements dating to this period have been discovered and excavated by archaeologists. As for Meroe and the south of the kingdom, practically nothing is known. From what can be gleaned from the archaeological record and literary documents, the Kushites kings continued managing affairs of the state, building and renovating temples, and mounting military expeditions. The Kushites were defeated by the Egyptian king Psammetichus II, possibly during the reign of Aspelta (ca. 593 BCE) at a battle near the Third Cataract. However, beliefs that Psammetichus II reached the Fourth Cataract and sacked Napata are unsubstantiated. This might have encouraged the Kushites to move farther south.

Although there is archaeological evidence that Meroe had been occupied since at least the eighth century (notably as the Napatan royal residence since the fifth century), the focus of the Kushite kingdom had been until then on Napata and the north. The Meroitic period begins shortly after 300 BCE with the relocation of the royal cemetery from Nuri to Meroe, the first pyramid there being that of King Arkamani I (ca. 275-250 BCE).

From that moment on, Meroe became the center of the Kingdom of Kush. Important cultural changes occurred during the Meroitic period as the Kushites gave their own traditions and customs prominence over many borrowed from Egypt. The most significant change is that of the language. For the first time in Kushite history, the native language, Meroitic, became the official language of the kingdom, and a hieroglyphic alphabet derived from Egyptian signs was created to write it.

Temples were built not only to the Egyptian god Amun but also to the indigenous lion-headed god Apedemak (the best known of the Kushite gods). The architecture favored for the lion temples is much simpler than Egyptian temples (although inspired by it) and generally consists of a single room with a large pylon (main gate). Even the relief decorations on temple and tomb chapel walls changed to suit the Meroitic idea of beauty, power, and fertility. The qore (Meroitic word designating the king as commander) and the kandake (ruling queen) wore a different royal costume, which was modified from that of Egyptian kings. The Kushites used centuries-old pharaonic influences and ideas from the Mediterranean world and incorporated them with their ancestral customs to create something different and truly their own: Meroitic culture.

At the time when Egypt had become a province of the Roman empire, the Meroitic Kingdom of Kush was a force to reckon with. The wrath of the Meroites was provoked when the Romans tried to take over Lower Nubia. Led by mighty leaders, the Kushites sacked Aswan, Elephantine, and Philae. The Romans retaliated by sacking Napata, but both parties eventually worked out an agreement. The great kandake who held strong against the Roman Army is believed to be Amanishakheto.

The Meroites still held power over lower and upper Nubia until the mid-fourth century CE. Military campaigns by Ethiopian rulers of the Kingdom of Aksum as well as the decline in wealth and political power of the royal family appear to have brought the Kingdom of Kush to an end.

Bibliography O’Connor, David. Ancient Nubia: Egypt’s Rival in Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993. Shinnie, P. L. Ancient Nubia. London and New York: Kegan Paul International, 1996. Welsby, Derek A. The Kingdom of Kush: The Napatan and Meroitic Empires. London: British Museum Press, 1996. Wildung, Dietrich, ed. Sudan Ancient Kingdoms of the Nile. Paris and New York: Flammarion, 1997