German Operations

During early March Admiral Schmundt ordered four U-boats west of Bear Island to attack the expected PQ12 convoy south of Jan Mayen, U377 and U403 requested from Narvik to join his waiting patrol line. Together with U589, they formed the Blücher group on 11 March, although U377 emerged almost miraculously unscathed after she was attacked in error by a flight of Junkers Ju87 dive-bombers near Moskenstraumen shortly after leaving port.

On 10 March the U-boat group Umhang was formed, comprising U436, U454 and U456 north-west of the entrance to the White Sea, but failed to successfully engage the enemy during its six-day existence. Hackländer’s U454 did report the sighting of ten steamers, four destroyers and two escort vessels on 12 March but was unable to achieve a firing position before losing contact and the information came too late for Luftwaffe intervention. Fellow Umhang boat U456 also attempted to attain a favourable attacking position but was unable to do so before the convoy disappeared from sight. U454 had been in Trondheim as part of the screen for Tirpitz’s move north and to allow shipyard repairs. Sailing back into action on 24 February, Matrosengefreiter Josef Kauerlost was lost overboard in high seas only two days after departure. Dönitz was fiercely critical of the Umhang boats’ dispositions so close to Murmansk, citing their lack of manoeuvre room in such proximity to the coast as the primary reason for their inability to attack. To operate effectively a U-boat needed space to outpace its target, running surfaced beyond the horizon and then lying in wait across the convoy’s predicted path.

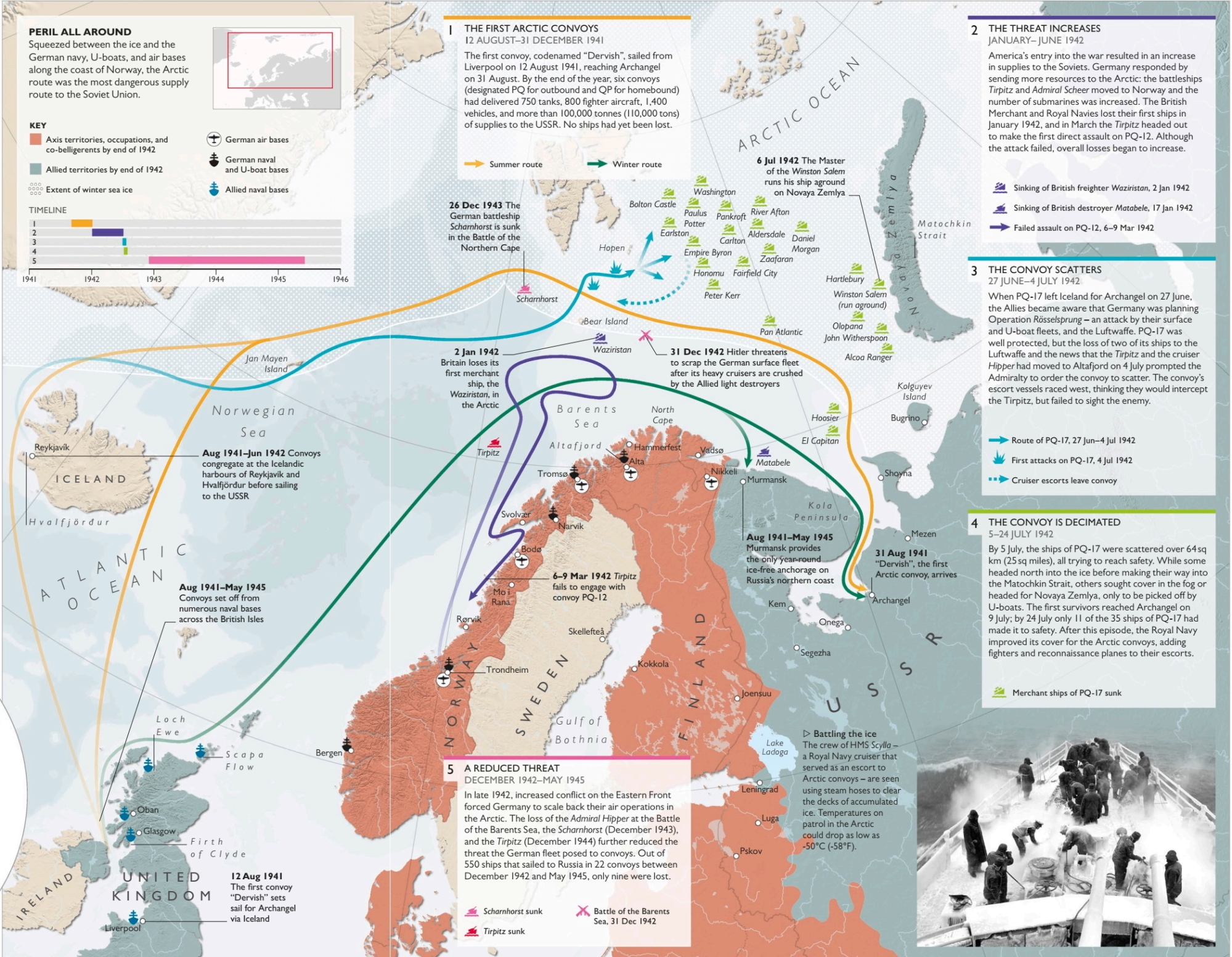

PQ12 sailed from Reykjavik on the first day of March under escort by HMS Renown, Duke of York, Kenya and six destroyers, with additional heavy forces sailing from Scapa Flow to rendezvous south of Jan Mayen Island. It was a formidable show of Royal Navy strength and Tirpitz sailed four days later to attack, escorted by destroyers and torpedo boats. A U-boat screen, combined with Luftwaffe reconnaissance, engendered confidence that PQ12 could be found and attacked. To add to the impending maelstrom, westbound convoy QP8 sailed from Murmansk, expecting to pass the inbound traffic near Bear Island. However, despite the number of vessels at sea, the two fleets managed to probe the seas around Bear Island without making any contact before Tirpitz returned to Norway, shadowed and unsuccessfully attacked by British carrier-borne aircraft. A single slow Russian freighter straggling from QP8 – 2,815-ton SS Ijora – was found by destroyer Friedrich Ihn and sunk with torpedoes, while U134 and U589 were both ordered south-east of Jan Mayen in a final attempt to find the elusive convoy. Both the U-boat and Luftwaffe reconnaissance had failed completely: PQ12 safely reaching Murmansk on 12 March.

Of course, unbeknownst to the Kriegsmarine, British code-breakers had managed to provide intelligence that enabled the re-routing of PQ12 out of harm’s way. The vaunted Enigma code used by all branches of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen SS had been broken in various stages. The U-boat service, though perhaps the most security conscious of all the Wehrmacht, was no exception at this point in the war; Enigma messages that provided plans and locations were read and decoded within hours. Though the introduction of a new rotor and expanded cipher in February 1942 would see an intelligence ‘blackout’ for most of that year, by December this new Enigma’s cipher – ‘Shark’ – had also been mastered. The scale of advantage offered to Allied forces by the breaking of the Enigma codes can barely be overstated.

The Blücher U-boat group was moved north into the Arctic Ocean near Petermann Land while Umhang disbanded; U405 and U592 waited south-east of Franz Josef Land and soon grouped with incoming U586 to form the Wrangel group though the middle of March remained unsuccessful:

One of the principal tasks of the Navy is to disrupt enemy supplies to Murmansk and Archangelsk in order to safeguard northern Norway and support Army operations against the Soviet Union. This task is not being fulfilled at the present time. Supplies are being shipped to Russia almost undisturbed … So far very few U-boats (three or four at the most) have been committed in the Arctic area. Experience shows that possibilities for successful U-boat operations definitely exist. British convoys to Murmansk and Archangelsk are forced to sail through an area, which the ice border limits to from 180 to 200 miles at the most. (The distance between the southern tip of Bear Island and the latitude of the North Cape is 190 miles; the distance between the North Cape itself and Bear Island is 228 miles.) Assuming that the enemy will approach the Norwegian coast no closer than 100 miles because of German forces, only a strip about 100 miles wide remains to be watched. It is impossible to patrol this area and attack enemy convoys with two or three U-boats. However operations by six U-boats would be very promising. In cooperation with air reconnaissance it must be possible effectively to hamper, if not entirely disrupt, enemy shipping in the Arctic area. The depth of the water is favourable for U-boat warfare … Therefore it is not possible to withdraw the submarines from Iceland or the Arctic Ocean, for example for promising operations off the U.S. coast; on the contrary, convoys to Russia should be considered a particularly valuable target for our U-boats. To intercept them it is much better to station several submarines in the Arctic area (Bear Island – North Cape) than in the Iceland – Hebrides area. The Naval Staff therefore makes the following suggestions to the Chief, Naval Staff:

a. The Arctic Ocean submarines of the Admiral, Arctic Ocean should be increased to at least 10 or 12 (including those in Narvik).

b. Submarines east of Iceland should be increased to five or four.

c. Submarines stationed northwest of the Hebrides should be withdrawn.

Fresh determination to intercept PQ convoy traffic spurred a strong U-boat and destroyer commitment against PQ13. The fact that Tirpitz only narrowly evaded damage from aircraft resulted in Hitler ordering extreme caution in the use of major surface units if there was any possible presence of an enemy carrier. Regardless, the convoys had to be stopped:

Most reports concerning British and American plans agree that the enemy is trying to maintain Russia’s power of resistance by means of great quantities of supplies and to open a second front in Europe in order to divert German forces from Russia. The regular heavy convoy traffic from Scotland to Murmansk or Archangelsk can serve both purposes. Therefore we must consider the possibility of enemy landings on the Arctic coast, in which case the nickel mines in northern Finland which are indispensable to us are most likely to be attacked. This remark introduces the Führer directive, which stipulates that all available means should be used to disrupt sea communications between the Anglo-American powers and Russia in the Arctic Ocean, which are practically intact so far, and to overcome the enemy’s supremacy at sea which extends into our own coastal waters.

PQ13 became the focus of Jürgen Oesten’s new U-boat command. To locate the incoming convoy U435, U589, U454 and U585 were ordered to patrol sectors of the AC quadrant close to the Murman coastline. PQ13 left Reykjavik on 20 March; sixteen freighters and a fleet oiler were escorted toward Murmansk by three whalers, due for transfer to the Soviet Navy as minesweepers, as well as three Royal Navy trawlers, two destroyers and a light cruiser. They left the convoy between 23 and 25 March, escort duties then taken over by two Soviet destroyers and the Royal Navy’s 6th Minesweeping Flotilla from 27 March.

The returning convoy QP9 cleared the Kola Inlet on 21 March, headed first for Iceland then onward to the United Kingdom. Two days later the U-boat group Ziethen formed: U209, U376, U378 and U655 lying north-west of Tromsø in the Norwegian Sea, waiting for PQ13 or outgoing QP9. It was here that Kaptlt Adolf Dumrese’s U655, on its first war patrol, was sighted by minesweeper HMS Sharpshooter south-south-east of Bear Island. The Halcyon-class minesweeper had come from the United Kingdom to Archangelsk with PQ5, assigned to carry out local duties in Russian waters, including ASW sweeps, minesweeping and local convoy escort. Sailing with the nineteen ships of QP9 – some returning empty, others carrying chrome, timber, potassium chloride and magnesium to Britain – Sharpshooter signalman Kenneth Hendry remembered the voyage:

We left the Kola Inlet as senior escort for the return convoy QP9, together with the destroyer Offa and two trawlers … and we were stationed ahead, doing the usual zigzag sweep. All was quiet until the evening of our third day at sea. It was dark but visibility was reasonable when the showers cleared.

I went on watch at 8pm. The weather was fairly calm but with frequent snow showers, keeping you on your toes at the end of each leg of the sweep to ensure that you were still on station and that none of the merchant ships was uncomfortably close, which often occurred in such conditions …

It was about 8.25pm and we had just turned and settled on to another ‘leg’ with a snow shower clearing ahead of us, when there was a hail from the leading-gunner closed up on the four inch on the foc’sle. Two or three cables away and about 10 degrees off our starboard bow we saw a U-boat lying beam-on with, as far as could be seen, no one on deck or in the conning tower. The Officer of the Watch called the captain and I sounded off action stations. The captain (Lieutenant-Commander David Lampen RN) immediately called the engine room for emergency-full-ahead and the ‘Stand by to ram!’ – and we had just begun to gather speed when we struck the U-boat just abaft the conning tower. She turned across our bow, listing, and bumped down our port side, obviously sinking as she went, and finally disappeared into the gloom astern. It was all over very quickly. Sharpshooter had stopped engines, damage control parties had already been mustered and I was ordered to signal by lamp to any ship I could see, ‘Have rammed U-boat – think I am sinking – please stand by me’. I managed to flash the signal to two merchant ships coming up astern but they were probably too preoccupied with avoiding us to read the signal. Later damage control parties reported that the forward mess deck was shored up and the pumps were coping, and Offa came alongside. She was instructed to take over the convoy and leave us to proceed at slow speed independently. The next few days as we limped along were pretty worrying, but the weather proved kind and we eventually reached Iceland.

Dumrese’s U655 rolled over with the impact and sank stern first, no trace of her or her forty-five crew remaining except for two lifebuoys and what the British observers took to be a canvas dinghy. The Russian convoys had sunk their first U-boat.

Although QP9 escaped attack, elements of PQ13 were found by U376 who immediately began shadowing and sending position reports. The voyage had been uneventful until 24 March when the convoy encountered an Arctic storm that raged for four days and nights and dispersed the convoy over a straggling distance of 150 miles. The nineteen merchants gradually formed small groups for mutual protection: one of eight ships and one of four, while the remainder proceeded independently. One of the latter, 4,815-ton SS Raceland carrying tanks, trucks and aircraft, was found by the Luftwaffe on 28 March and sunk by two near misses that ruptured the hull. The entire crew abandoned ship in two boats, but only one containing twelve men reached the shore where Norwegian civilians rescued them and took them to the Kriegsmarine hospital in Tromsø. The 7,008-ton SS Empire Ranger was also hit and sunk by the Luftwaffe that same day, all forty-seven crewmen abandoning ship and rescued by the German destroyer Z25, one of three from the 8th Zerstörerflottille that had been added to the attack on PQ13.

The following day the German destroyers attacked in appalling visibility and strong snow flurries, sinking the 4,687-ton SS Bateau before coming under attack by destroyer HMS Fury and cruiser HMS Trinidad in the early hours. Z26 was badly damaged and later sank following further attacks by the Royal Navy and Russian destroyer Sokrushitelny. Ironically, HMS Trinidad was disabled by one of its own torpedoes after the weapon’s gyroscope froze and sent it circling. As the German destroyers disengaged, so too did the British: Trinidad limping for the Kola Inlet. From the sinking Z26 the remaining German destroyers rescued eighty-eight survivors while U378 took eight others aboard and headed for Kirkenes.

On 30 March, U-boats that had been hastily grouped into the new pack Eiswolf finally succeeded in attacking the scattered convoy. They had already suffered at the hands of convoy escorts during the preceding days; the retreating U378 depth charged by HMS Fury and U585 was forced to abort its patrol after depth charge damage to all forward torpedo tubes. Worse was to come for Kaptlt Ernst-Bernward Lohse’s battered U585 as it headed for Kirkenes but blundered into a German mine that had broken free from its mooring in the ‘Bantos A’ barrage. The U-boat was destroyed with all forty-four crew finally listed as missing on 8 April.

Oberleutnant zur See Friedrich-Karl Marks’ U376 found and torpedoed straggling 5,086-ton SS Induna at 8.07 a.m. The convoy’s vice commodore’s ship, Induna, had attempted to corral five other vessels into a group after the storms had abated. Sixteen men, who had prematurely abandoned the freighter Ballot after damage by Luftwaffe bombs, were taken aboard – the remaining crew taking the damaged Ballot into Murmansk. Separated from the remainder of PQ13, Induna was accompanied by whaler HMS Silja before both became stuck in ice the following day. Once freed, the steamer took Silja in tow, the small warship’s fuel almost exhausted. In heavy seas the following night the tow parted and once again Induna was alone. Unbeknownst to the merchant’s master, William Norman Collins, Kaptlt Heinrich Brodda’s U209 had sighted the steamer and missed her with two torpedoes at 5.52 a.m. Undeterred, Brodda gave chase in order to fire again.

At 8.07 a.m. Marks hit Induna with one of three torpedoes, the freighter catching fire and slewing to a stop. A coup-de-grâce torpedo sent the boat under, bow first. Marks did not linger at the scene as lookouts sighted a nearby periscope, presumed to be Russian. It was, however, Brodda: beaten to the punch by his flotilla mate after his prolonged chase. Forty-one survivors abandoned ship in two lifeboats, but only thirty living men were later rescued by a Russian minesweeper. Austin Byrne was a DEMS gunner aboard Induna:

Have you ever thought of anyone you would like to have a word with, someone famous perhaps or someone from your schooldays? Well I would pick the most wonderful man, who I consider that I have ever met. Sadly I do not know his name; all that I know is that he is buried in the Naval Cemetery in Murmansk, North Russia … We had been adrift for four days in the lifeboat, after the submarine U376 had torpedoed the Induna on the 30th March 1942. This man was not a crewmember of the Induna but was aboard the Ballot when she was sunk, and you could say that they were very unfortunate in ‘being in the wrong place at the wrong time’.

The long-range German planes found the ships and homed in on the destroyers for an attack, this was beaten off by the cruiser HMS Trinidad, but then the JU88 and high level Focke Wulfes attacked with bombs. The Ballot suffered some very near misses from a dive bomber attack and lost steam which caused her to drop astern of the convoy, a lifeboat was lowered with sixteen men aboard and they were picked up by the Whaler Silja which was herself on passage to be turned over to the Russians, she was one of three that had been sent, one was sunk and the other turned over in the ice. A few ships went north to get near the ice, but the Induna got stuck and while the other ships sailed on, the Silja stayed and as she was a small ship with limited room, the men from the Ballot walked over the ice onto the Induna. The Silja then ran out of fuel so the Induna took her in tow but at about 10 pm the tow broke and the two ships parted.

The next morning … the Induna was torpedoed in the number five hold right under a load of aviation spirit and the explosion turned the deck into a burning mess. We were sent to boat stations and a few people started to run through the fire, whilst some on the stern jumped into the sea and away from the flames. The last man was one of those rescued from the Ballot and he had no shoes on so his feet were ripped open by the cargo of barbed wire which we were also carrying, and he was leaving bloody footprints as he made his way to the lifeboat station, the Mate then lowered the boat to deck level and myself with some others were ordered into the boat, this was when we saw this man coming towards us, his hair was burnt off and his face and hands were badly burnt, as his jacket and trousers were also burning we rolled him into the boat and beat out the flames.

The boat was lowered into the sea and as we rowed away another torpedo smashed into the ship, which then sank with all the men who were still aboard. We were in the lifeboat for four days in terrible weather, after all it was winter in the arctic and we were in the Barents Sea. The burnt man had few clothes and he sat in the boat with the seas breaking over him and we covered him with a blanket and a spare coat, the other six in the boat were of no help, so the gunner and myself did all of the baling. We tried to talk to this man but the poor soul could hardly talk, but I did get out of him that he came from America. The seas broke over him and a coat of ice formed on him which got thicker as time went by, but never once did he moan but just sat quietly and all that he ever asked for was the occasional cigarette, which I would light for him and put it into his mouth, he would then try to move his head when I should take it out, and that was all that he asked for, a few times a day he would say ‘gunner, can I have a cigarette?’

This went on for the four days that we were adrift, and then at dusk on the fourth day we sighted land, when we told him he asked ‘gunners will you please turn the boat so that I can see it’, and this we did, his next words were ‘put an oar into my hands and I can rock my body to help’, at this time his hands were twice as thick as they should be, with his fingers drawn and bent with the cold, all black with knuckles burst and covered with scabs, and still he wanted to help!

Then we saw the rescue boats and were picked up, as I was pulled aboard I saw a Russian sailor down in the lifeboat looking at him and a rope being passed down, I do not know how they got him out of the lifeboat as I was taken to the bridge. The next time that I saw him was after one of the females in the Russian crew called to me, she was having difficulty with the cabin boy, a seventeen-year-old lad called Anderson, who was frozen bent double, and having cut his jacket off I saw that he was black to the waist, when she saw this the Russian said to leave him.

After a few tots of vodka I was taken to see the burnt man, who put out his hand to me and said as best he could ‘We made it kid’, words that I will never forget from a man who was now suffering from both burns and terrible frostbite. The next day we arrived in Murmansk and were put into the Russian Hospital, where I went to sleep and when I woke up I was told that the cabin boy had died and later that the American had also died from his injuries. Who was he? I will never know for certain but there is a grave in Murmansk to an unknown sailor from the Ballot, a man who died with dignity, a man who anyone can be proud to say ‘I met that man’. His family can also be proud of him, but the sad part is that no one in America knows anything about him.9

The second ship to be sunk by U-boat from PQ13 was 6,421-ton American merchant Effingham, one of the small group of vessels temporarily gathered by Induna following the storm. Kapitänleutnant Max-Martin Teichert’s U456, on its first war patrol, attacked two straggling merchants at 10.36 a.m.; a spread of three torpedoes missed Honduran Mana, but a fourth hit Effingham amidships on the port side, bringing her to a stop. The cargo was general war supplies but also a heavy load of explosives so the crew abandoned ship as she began to settle by the stern, two men falling overboard and drowning. A stern tube coup de grâce missed, after which the damaged freighter was lost from vision in a snow squall. Teichert’s crew hastened to reload all torpedo tubes and attempt to find the damaged steamer. Meanwhile Kaptlt Siegfried Strelow’s U435 found the American, missing with an initial salvo of two torpedoes and hitting with a third while attacking surfaced in driving snow; the ship exploded and sank following a final torpedo hit in the bow. Thirty-one of the forty-three crew were later rescued.

Although other ships of the convoy were chased by U-boats, there were no further attacks: most ships docking in Russia on 30 March and the final straggler entering harbour on 1 April. The Germans too had suffered heavily: one destroyer and two U-boats destroyed for the destruction of five merchant ships – two to the Luftwaffe, one to a destroyer and two to U-boats. German surface ships in Norway already contended with severe fuel shortages and the decision was made that henceforth destroyers would only be used against enemy convoy traffic if the enemy’s location was definitely known and conditions for success favourable. Although PQ13 had gotten off comparatively lightly, the loss of over 25 per cent of the convoy was unacceptable. Both the Home Fleet commander, Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Tovey, and the first sea lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound, argued strenuously that the PQ convoy size should be radically reduced so as to provide a smaller target to locate. With extreme pressure from Washington to move supplies to Russia, Churchill was given no other option than to insist that the convoys remain as they were if not become larger.

It was not only the Kriegsmarine threat that had increased for the Murmansk run. The Luftwaffe had begun to strongly reinforce their presence in northern Norway and by June could muster 103 Ju88 bombers, 42 He111 torpedo bombers, 15 He115 torpedo bombers, 30 Ju87 dive-bombers as well as 8 Fw200, 22 Ju88 and 44 Bv138 reconnaissance aircraft.

During April the Soviet Navy amplified its submarine attacks off Nordkyn and Makkaur, despite the nights getting increasingly shorter with the Arctic spring. U-boats too had been bolstered in anticipation of PQ14, expected in mid April. Two U-boat groups were formed: Naseweis comprising U334, U592 and U657 stationed off Jan Mayen, and Bums comprising U334, U377, U403, U589, U591 and U592 west of North Cape. By 9 April fourteen U-boats were at sea within the Arctic, a further five in port scattered between Kirkenes, Narvik and Trondheim. The U-boat groups morphed as they waited for the incoming convoy, eight boats forming Robbenschlag, directed to new patrol areas by Oesten in Kirkenes. On 9 April PQ14’s 24 merchant ships were spotted by Luftwaffe reconnaissance, the sixteen ships of outbound QP10 shortly thereafter. With a sparse escort, the decision was taken to send destroyers against QP10, as well as Robbenschlag boats, three U-boats finding and beginning to shadow the convoy on 12 April. While the destroyers failed to make contact and aborted their mission, the U-boats opened their attack in heavy seas.

At 0.59 a.m. on 13 April Seibicke’s U436 fired torpedoes while submerged, hitting what he estimated was a 4,500-ton steamer: 5,823-ton Russian steamer Kiev, laden with chrome and timber, sinking within seven minutes and the crew abandoning ship in three lifeboats. Five crewmen were lost, a fifth female crewmember later dying from wounds after rescue by escorting ASW trawler HMT Blackfly. Half an hour later Strelow’s U435 also torpedoed a steamer from QP10: the 6,008-ton Panamanian El Occidente hit in the engine room and nearly breaking in half, sinking so rapidly that no lifeboats could be launched. The ship was carrying only a part cargo of chromium ore as ballast, twenty crewmen killed and a further pair rescued by HMS Speedwell. The U-boats then lost contact with QP10 in the heavy weather, Strelow later finding the abandoned 5,486-ton steamer Harpalion that had been damaged by Ju88 attack earlier that day. Three G7a torpedoes were fired, the third striking the ship astern and sending her under with its 600-tons of ballast mineral ore. One further ship had been sunk by the Luftwaffe before the convoy passed out of range, further U-boat attacks having been frustrated by bad weather and Robbenschlag ordered to abandon the hunt and focus attention on PQ14.

Ironically, the inbound convoy was largely defeated not by the Luftwaffe or Kriegsmarine, but by the weather. During the night of 10 April PQ14 encountered heavy ice south of Jan Mayen and was scattered by the elements. Many ships suffered ice damage and others failed to rejoin the convoy body, so much so that sixteen ships returned to Iceland, leaving only eight to continue under escort by the cruiser HMS Edinburgh and twelve other warships. Luftwaffe attacks yielded no results and only Kaptlt Heinz-Ehlert Clausen’s U403 from the ten-boat strong Blutrausch successfully hit the convoy commodore’s ship SS Empire Howard north-west of North Cape on 16 April. The ship, carrying 2,000 tons of war materials, went down in less than a minute – thirty-seven of the sixty-two crew rescued by escorting trawlers and commodore Captain E. Rees RNR among those lost. U376 also launched a torpedo attack against HMS Edinburgh, although despite recording the sound of three detonations, all shots missed. It was a meagre result for the U-boats, thwarted by a combination of aggressive escorts, bright skies and bad weather.

In Britain further entreaties from Tovey to reduce the PQ convoy size at least until pack ice had receded fell on deaf ears and PQ15 of twenty-five heavily escorted merchants sailed in late April for Murmansk. The political pressure on supplying the Soviet Union remained intense and Royal Navy operational considerations relegated to secondary concern. Within the Kriegsmarine too, there was concern at the U-boat operations within the Arctic, not least of all the difficulties caused by operational control being split between Schmundt’s post as Admiral Nordmeer and Hermann Boehm as Marineoberkommando Norwegen. Schmundt’s authority – and therefore that of Jürgen Oesten – only covered boats within a central band of the Arctic Ocean, those operating further west falling within Boehm’s authority. Both officers agreed that this was unwieldy and untenable. They reasoned that Schmundt’s authority should extend over a larger operational area representing an ‘organic whole’, so that he himself would be in the position to commit forces over a greater region allowing more streamlined and unified planning. Schmundt’s command area was soon extended eastward approximately from the line of the Lofoten Islands–Jan Mayen and Schmundt was given operational responsibility guided only by directives from above. The post of Admiral Nordmeer was placed directly subordinate to MGK Nord, thereby eliminating tedious links in the command chain.

Such directives were soon forthcoming from SKL demanding improved operations against the PQ convoys. U-boats were to be stationed further west to locate and attack traffic earlier and if convoy location reports were good and the convoy proceeding on large zigzag courses, U-boats were instructed to attack from a deeply echeloned patrol line slowly moving west. Heeding Dönitz’s admonitions, the narrow approaches of Kola Bay were not to be patrolled by U-boats but the Luftwaffe instead.

The fresh instructions yielded little against PQ15 or its reciprocal convoy QP11 that left Murmansk on 28 April. Nine boats of the Strauchritter group were gathered in the Barents Sea south of Bear Island, two of them passing from Boehm’s western waters command into Schmundt’s direct control. During the night of 29 April, in high seas and driving rain, Kaptlt Heino Bohmann’s U88 made contact with QP11, 150 miles north-east of Vardøe. Soon thereafter Kaptlt Heinrich Timm’s U251 and Kaptlt Hans-Joachim Horrer’s U589 also gained contact. At 6.03 a.m. the following morning Bohmann fired a spread of three torpedoes toward the convoy, recording a single detonation after nearly four and a half minutes of running time, although no ship was recorded as hit. Bohmann was confident that he had at least damaged a large steamer, while other U-boats reported that the heavy sea made it impossible to attack while submerged. Neither U405 nor U713 – the boats previously under Boehm’s control – east of Jan Mayen made contact and Schmundt ordered them into the waters between Bear Island and the North Cape to await PQ15.

Meanwhile at 11.42 a.m., U456 sighted the westbound HMS Edinburgh, deduced to be part of QP11’s escort. Radioing a contact report, Seibicke’s U436 was also able to find Edinburgh and fire a fan shot of four torpedoes at the zigzagging target, missing with all of them and later badly damaged by retaliatory depth charges from QP11 destroyers and forced to return to Trondheim. Teichert’s U456 clung onto the fast moving cruiser and at 4.18 p.m fired torpedoes, scoring two hits in spite of the bad weather making aiming difficult. Edinburgh was reported aflame and listing heavily though still afloat: three destroyers arriving to shepherd the damaged ship back to Murmansk. With heavy seas causing attack periscope problems, a frustrated Teichert was unable to mount another attack and was ordered to remain as contact boat to bring U88 to the scene.

HMS Edinburgh had been sailing some 20 miles ahead of the convoy, carrying £5 million in Russian gold bullion as payment to the United States for war materials, when Teichert’s torpedoes hit the starboard side, nearly severing the ship’s stern. HMS Foresight and Forester accompanied by two Soviet destroyers arrived to shield the crippled ship and begin towing back to port while Teichert continued to shadow. Ultimately, three of the German Arctic destroyers, who had sailed against QP11 but been forced away from the convoy, engaged the crippled cruiser and its depleted escort after the Soviet ships had departed to refuel. Z24 hit the cruiser again while the destroyer Hermann Schoemann was herself hit by fire from Edinburgh. The two Royal Navy destroyers also suffered damage before the battle ended: the doomed Edinburgh was sunk by a British torpedo and Hermann Schoemann by a German; 200 German crewmen were rescued by Z24 and sixty were plucked from a life raft by U88 and taken to Kirkenes. U456 had attempted one final attack after the destroyer action had finished, but was forced underwater and depth charged to such a degree that Teichert asked permission to return to Kirkenes, encountering wreckage from the sunk cruiser while en route, including rising oil, life rafts and pith helmets.

Contact with QP11 was maintained despite icebergs and bad weather and at 3.13 a.m. on 1 May Horrer’s U589 fired two torpedoes and hit 2,847-ton Soviet motor merchant Tsiolkovskij, badly damaging the ship that was later sunk by the retreating Z24 and Z25.

Meanwhile PQ15 had come under Luftwaffe attack, including six KG26 He111 torpedo bombers during the early morning half-light of 3 May: the first time these aircraft had been used in action. They claimed three ships sunk and another damaged, though in reality two were sunk and one damaged. This damaged ship was 6,153-ton freighter Jutland, subsequently found on 3 May by U251. Kapitänleutnant Timm had fired his first torpedo in anger two days previously against an escorting destroyer, but missed. A little past midnight on 3 May, Timm’s lookouts sighted Jutland emerging from a cloud bank and Timm dived to attack the ship; three torpedoes fired at a range of 3,500 metres, one hitting the ship whose cargo included 500 tons of cordite and 300 tons of ammunition. The resulting explosion was clearly audible as the freighter virtually disintegrated. Jutland had in fact already taken damage from Luftwaffe bombs and been abandoned when Timm attacked, but escort forces still homed in on U251 and depth charged the boat until Timm crept clear. The following day U703 passed the scene of the sinking and found large amounts of wreckage and six empty lifeboats. The remaining merchants of PQ15 reached Russia unscathed, U-boats foiled by aggressive escorts and intense depth charging.

Results had been disappointing and the lengthening hours of daylight robbed U-boats of their greatest ally: darkness. Despite Dönitz’s continued requests to return the boats to the Atlantic, the commitment of Arctic U-boats remained in force, though Dönitz at least agreed that they be used for convoy interception rather than support for land operations. During the night of 27 April, Soviet troops had landed in three places behind the Wehrmacht’s front line along the coastline of Motovski Bay. Urgent army appeals for Kriegsmarine help were denied: particularly calls for U-boats to harass Soviet landing craft, deemed too small to be targeted by torpedoes and too fast for gunfire while U-boats would expose themselves to extreme risk operating so close inshore.