Throughout the war on the Eastern Front, the German cavalry played a more active and traditional role than in France. With localized exceptions, World War I from the Baltic coast to Rumania remained a war of movement. It could not be otherwise. Between Riga and the mouth of the Danube lay an airline distance of more than eight hundred miles (nearly 1,300 km), but the front could never be measured in airline distances because it included many hundreds of miles more in twists and turns. One theater of operations that was of central importance to Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia alike, namely Russian Poland, by itself measured more than 200 by 250 miles (320 by 400 km). Completely entrenching such vast distances was simply impossible. The front would always be “in the air” somewhere. Consequently, “both sides attempt[ed] vast and daring maneuvers against the enemy’s flank and rear, just as they would in a later war from 1941–1945.” For the success of any such maneuvers, the cavalry’s mobility remained critically important.

At the war’s beginning, the Russian army mobilized no fewer than thirty-seven cavalry divisions. On the German side, by dramatic contrast, there was only one, at least in East Prussia. This was the venerable 1st Cavalry Division, whose regiments were based at Königsberg, Insterburg, and Deutsch-Eylau. This division, along with eleven neighboring infantry divisions, comprised about one-tenth of Germany’s mobilized strength in 1914. Though the numbers of German cavalry would grow enormously during the war on the Eastern Front, the initial disparity was owing not only to Russia’s having to fight both Germany and Austria-Hungary and therefore needing more cavalry but also to the German General Staff’s assigning East Prussia a secondary status in prewar planning. Primary attention and the accompanying resources went to the massive attack against France and Belgium in the West. This particular German cavalry division, however, not only comprised storied Prussian regiments; it would also subsequently be maintained as part of the Reichsheer during the interwar period and go to war again on horseback in 1939.

One of the very earliest events on the Eastern Front also involved cavalrymen, though in this case they weren’t German. On 6 August 1914, several hundred men of a formation known as Pilsudski’s Legion—carrying their saddles—marched across the frontier of Russian Poland from Austrian Galicia near Cracow in the hopes of finding mounts. Wisely, they retreated when they were approached by Cossacks and eventually found their way into the Austrian army. The incident is revealing, for the Cossacks’ presence on the Eastern Front from the war’s outbreak reinforced the conflict’s likely intensity over the whole of that almost immeasurably vast area. From its beginning, the fighting in the east, unlike that in the west, carried overtones of “race war,” a feature reaching its gruesome extreme in the Nazis’ campaigns between 1941 and 1945. The prejudices between supposedly cultured Germans and supposedly barbarous Russians, with the Poles caught in the middle, were manifested from the beginning of the war of 1914. As early as 11 August, no less an authority than the director of the Prussian Royal Library in Berlin, Adolf von Harnack, pronounced that “Mongolian Muscovite civilization” once again loomed over the eastern horizon to threaten German lands just as had happened in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

This conjuring of the ancestral Western European fear of the horsemen of the steppe could not have been clearer. As it turned out, the very next day Cossacks of Russian general Pavel Rennenkampf’s First Army crossed the East Prussian border, sacked the village of Markgrabovo, and ignited precisely the sort of panic that Harnack’s “Mongolian Muscovite” hordes had created in generations past. Intensifying the German reaction was the quasi-melding of Prussia’s identity with that of Germany as a whole, a process that had begun with Germany’s unification under the direction of Otto von Bismarck in 1870–1871. Though certainly not universal, this identification of Prussia with Germany made East Prussia’s violation by “asiatics” a national concern, not one limited to East Prussia itself. For a traditionalist unit such as the 1st Cavalry Division, Russian troops’ presence on German, and especially East Prussian, soil would pose a grave emotional threat. A prominent later commander in the post-1918 Red Army (and eventual Marshal of the Soviet Union) only reinforced the apprehension accompanying such a threat by evoking the memory of Mongols’ style of warfare. “The Russian Army,” boasted Mikhail Tukhachevsky, “is a horde, and its strength lies in its being a horde.” This image of rampaging barbarians who “would sweep into deutsches Kulturland” was hardly one to reassure East Prussians or other Germans either during World War I, the chaotic later days of the 1920s, or even in the 1930s or 1940s. As it was, the commander of the German I Corps in East Prussia in 1914, General Hermann von François, lamented the sorry plight of the “mad rush” of thousands of civilians away from the Russian horsemen and fretted that the refugees would impede his own armies’ efforts to contain the invaders. A senior staff officer who witnessed the invasion and who planned the defenders’ operations, Colonel (later General) Max Hoffmann, subsequently noted in his diary that never before had war been waged with such “bestial fury.” The Russians, he wrote with brutal succinctness, “are burning everything down.” Buildings not burned were plundered. One eyewitness, a captain in the Russian 1st Cavalry Division’s Sumsky Hussars, noted that in the campaign’s opening days around Markgrabovo, “[the] scene on the German side of the border was quite frightening. For miles, farms, haystacks, and barns were burning. Later on, some apologists…tried to explain these fires by attributing them to the Germans, who were supposed to have started them as signals to indicate the advance of our troops. I doubt this, but even if it were so in some cases, I personally know of many others where fires were started by us.” Not surprisingly, Russian cavalrymen, including the captain quoted here, helped themselves to the fine horses of East Prussia when in need of a quick replacement for blown, wounded, lame, or dead Russian mounts. Not a few of these horses came from the Prussian State Stud at Trakehnen, which lay almost directly in the path of the invaders. Some Cossacks also took human hostages from the civilian population, many of whom were deported to the east.

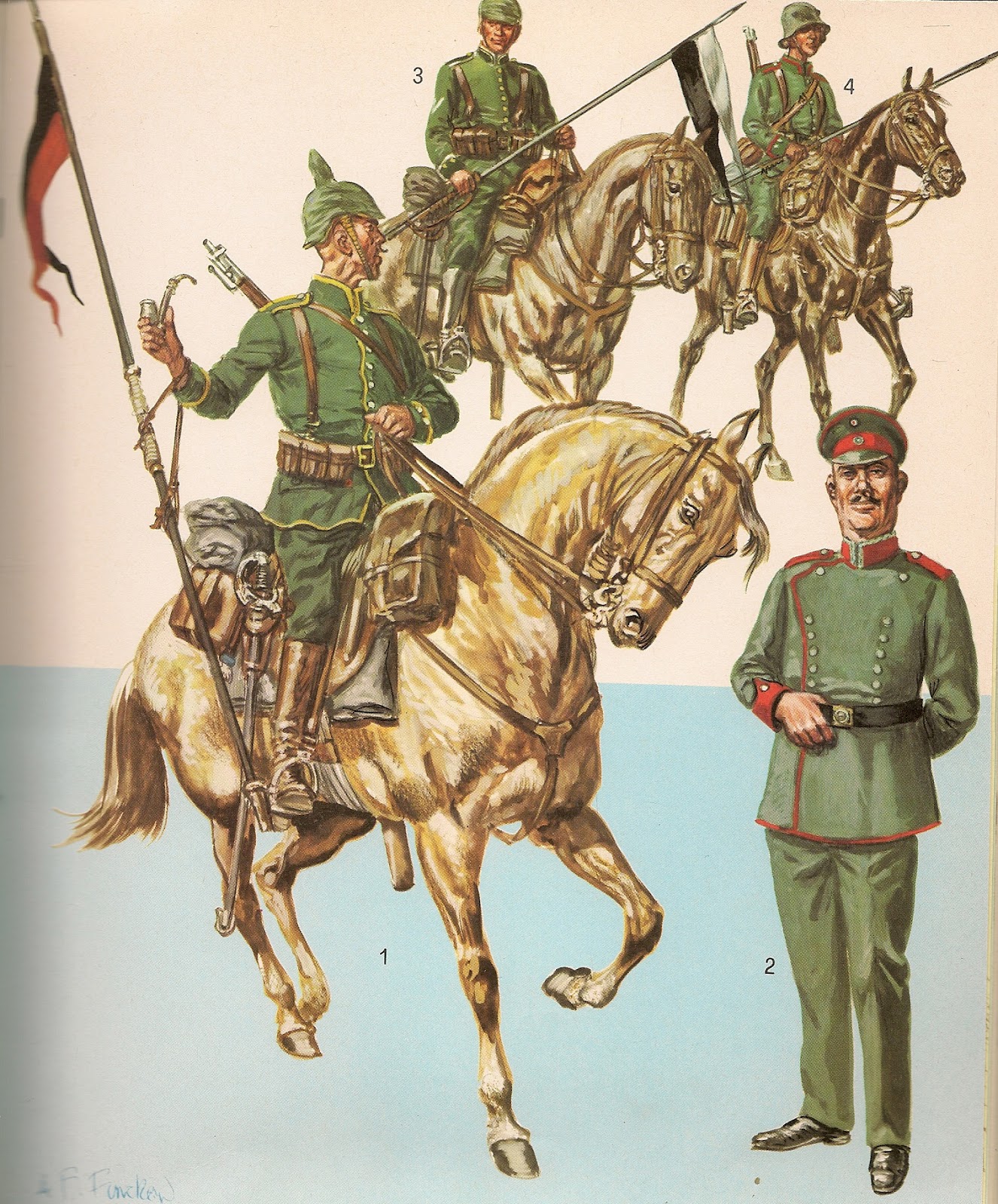

In resisting the Russian invasion, the German armies in East Prussia fought a successful series of battles between 17 and 23 August near Stallupönen and Gumbinnen. These towns lay due east of the provincial capital of Königsberg with Stallupönen being almost literally on the Russian border. Later, around Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes to the south and southwest, another string of even larger defeats would be inflicted on the Russians. In the fighting near Gumbinnen, the 1st Cavalry Division made a measurable contribution. Though they had sometimes failed to provide accurate intelligence of the Russian advance and been dismissed by the infantry as “frog stickers” because of the lances they still carried, the cavalrymen redeemed themselves. Flanking the Russians in good cavalry fashion, the German horsemen broke clear and played havoc with the Russians’ logistics and lines of communication. Having already served with the frontier defense (Grenzschutz) before its parent Eighth Army was activated, the 1st Cavalry Division had earlier fought at Stallupönen. Now, near Gumbinnen, it was in its element against a large but lumbering opponent advancing into the acute angle formed by the Gumbinnen-Stallupönen railway line and the River Inster. This opponent was the Russian Imperial Guard Cavalry Corps under the command of the Khan of Nakhitchevan. It had the mission of securing the Russian right wing. Fought to a standstill by German infantry and artillery around the village of Kaushen, the Russian cavalry faltered, and a gap opened in their front. Into that gap plunged the 1st Cavalry Division. The German horsemen broke through, and the ride was on—fully 120 miles (190 km) behind the Russian lines in barely three days’ time. It was a cavalryman’s waking dream for the division’s older officers. The division’s commander, General Brecht, had entered the Prussian army in 1867, and two of his brigadiers were well into their fifties. Still, the advance occurred in a fashion never duplicated on the Western Front after the first Battle of the Marne. It also created panic in General Rennenkampf’s headquarters. Proving themselves generally better horsemen than their Russian counterparts, the division’s troopers moved so far so fast into the Russian rear that they lost contact with their own forces. Consequently, the cavalrymen initially failed to get the subsequent orders for the great redeployment southwestward toward Tannenberg. As that redeployment got underway, however, the division was eventually given the cavalry’s other great task: to screen and protect the German movement and prevent the Russians’ taking advantage. Despite exhausted mounts, insufficient water, and reduced fighting strength, the horsemen had to harass and confound the Russians to keep Rennenkampf’s army from coordinating with General Alexander Samsonov’s to the southwest while the Germans pounced on the latter. Even though Rennenkampf continued to advance slowly but successfully toward Königsberg, the 1st Cavalry Division nevertheless managed repeatedly to put itself in the Russians’ way. Most importantly, this one cavalry division succeeded in frustrating the larger objectives of an entire enemy field army.

By stunning contrast, the Russian cavalry, three divisions strong between Gumbinnen and Tannenberg, not only failed to take any effective part in the former battle but also failed to exploit the real advantage of its own larger numbers in the latter. Nevertheless, and not a little unusually, it was the Russian 1st Cavalry Division that remained in constant reconnaissance-contact with the German 1st Cavalry Division’s horsemen and accompanying bicycle-mounted infantry, and that over a frontage of thirty-five miles. Thus the battles in East Prussia in August and September 1914 not only served to maintain the apparent viability of the German cavalry. They also had a much greater resonance, for they helped propel General Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff to the eventual supreme command of the German armed forces. These victories were ones that, according to one subsequent newspaper account, would for years haunt the children and the grandchildren of the Russian soldiers who’d been so thoroughly defeated there.

Somewhat later, in November 1914, several German cavalry divisions also played prominent roles in the German Ninth Army’s offensive into Russian Poland along a line stretching roughly northeast from Posen to Thorn. Aimed at the juncture between the Russian First Army and its neighbor to the southwest, the Second Army, the German offensive intended to relieve pressure on Austro-Hungarian forces to the south and simultaneously to forestall an impending Russian campaign aimed at the rich industrial region of German Silesia. While the Germans’ III Cavalry Corps stood in reserve and helped screen the southern end of Ninth Army’s line, the I Cavalry Corps comprising the 6th and 9th Cavalry Divisions had been assigned a more active role. Along with the accompanying 3rd Guards Infantry Division, the I Cavalry Corps had the mission of supporting Ninth Army’s broad southeasterly advance through the central lowlands along the left bank of the Vistula toward the Polish city of Lodz. Between 11 and 16 November, the Ninth Army, supporting the XXV Reserve Infantry Corps on the right wing of the German advance, covered more than fifty miles (80 km). On 17 November cavalry and reserve infantry were ordered to completely envelop Lodz to the south and west with attacks toward Pabianice. In doing so, they threatened the entire Russian Second Army at Lodz with encirclement and destruction. Unfortunately for the Germans, the Russian Fifth Army executed a heroic march northward to Lodz’s relief—two of the Russian infantry corps marched more than seventy miles (112 km) in forty-eight hours—and forced the German cavalry and reserve infantry to fight their way out the way they’d come. While the Russians could claim a victory in saving Second Army from destruction, the Germans could equally claim that Silesia had been preserved from invasion. In that strategic victory the horsemen of the I Cavalry Corps had played no mean part.

In 1915 the cavalry again played a significant role in a major German victory, this time in Lithuania. Having driven the Russians out of East Prussia at the beginning of the year in the Winter Battle of the Masurian Lakes, German armies joined with their Austro-Hungarian allies to expel Russian forces from almost the whole of Poland in a gargantuan offensive during the spring and summer. These offensives included the dispatching of a strong cavalry force into Courland (Latvia) toward Riga in April and May as part of Army Group Lauenstein (later redesignated the Niemen Army after the river of the same name). The cavalry moved ahead with orders to destroy the Russian railways wherever the horsemen found them. Near the town of Mitau (Jelgava), the German riders captured a baggage train, ammunition wagons, and machine guns. To the south, they also cut the Russian railway on both sides of the junction at Shavli (Siauliai) before falling back temporarily. This ride was followed up in early September with a drive farther to the southeast toward Kaunas (Kovno) and Vilnius (Vilna). Three German cavalry divisions participated in this attack on Lithuania’s two largest cities. In this offensive, begun on 8–9 September, the German horsemen supported the advance on Grodno, cut the Russian railway linking Vilnius and Riga at Sventsiany, and raided into the Russian rear areas as far as Molodechno and Smorgon, though the Russians subsequently managed to drive them and other German forces back and thus avoid encirclement. Indeed, the first German troops to enter Vilnius were the troopers of the Death’s Head Hussars who reminded one native of the Teutonic Knights of five hundred years before, but without the cross.

Similarly, in Rumania in 1916 German and German-led cavalry again had a prominent part to play in a significant victory. In the immediate aftermath of Rumania’s declaration of war on the Central Powers in August 1916, Rumanian offensives had not only gained the passes of the Transylvanian Alps but also the easternmost portion of the Great Hungarian Plain. Anticipating such a Rumanian invasion, however, the German and Austro-Hungarian governments, supported by a willing Bulgaria, had already planned an invasion of their own. This took the form of a combined counteroffensive starting on 18 September to drive the Rumanians out of eastern Hungary. That successful effort was followed by a push across the Transylvanian Alps into both Moldavia and Wallachia by German and Austro-Hungarian forces, as well as an invasion across the Danube by German and Bulgarian troops into the southern Dobrudja. Pushing the Rumanians back through the Vulcan, Red Tower, and Predeal Passes, the flank of the descending left hook of German general Erich von Falkenhayn’s Ninth Army was covered in part by a mounted corps. On 10 November the force began its advance down the Jiu Valley and into the lowlands of Wallachia north of the Danube. This region of Rumania constitutes the southwestern extension of the Black Sea or Pontic Steppe, a vast, undulating grassland interspersed with trees and stretching all the way to the Volga. In many respects, it was ideal horse country for the cavalry, at least as good as the Polish plains around Lodz. By 21 November the advancing German horsemen and infantry had covered the more than sixty-two miles (100 km) to the important rail junction of Craiova, which quickly fell to the Germans. By 26 November, the German horsemen and infantry had advanced another thirty miles (48 km) and captured the one remaining bridge over the Aluta River (at Stoenesti) not destroyed by the retreating Rumanians. They thereby helped open the way for the drive on Bucharest. They also once again demonstrated the cavalry’s utility on the Eastern Front in a fashion impossible in France.

In spite of these successes, however, the Rumanian forces in Wallachia southwest of the capital managed to launch a fairly strong counterattack on 1 December against Falkenhayn’s forces and those of General (and Death’s Head Hussar) August von Mackensen attacking from below the Danube. Here, too, however, the German cavalry made a signal contribution. To help stem this Rumanian counterattack, Falkenhayn dispatched a combined cavalry-infantry force against the right wing of the Rumanians. The horsemen and their accompanying infantry struck the right flank of the Rumanians, broke through, and got into their rear areas. In true cavalry fashion the German horsemen set about sowing confusion and inflicting heavy casualties on the Rumanians. As a consequence, they created a sense of panic that forced a Rumanian withdrawal. Bucharest fell shortly thereafter, and the Rumanians evacuated the whole of the Dobrudja. Those Rumanian forces still holding the lines in the great bend of the Transylvanian Alps were thus threatened with being cut off from the south. As a result, their position became untenable, and they too were forced to retreat into Moldavia. The setting in of heavy winter rains and snow, however, prevented the Germans from pursuing their defeated enemies. The year 1916 ended with the Rumanians holding a rump territory in Moldavia adjoining the Russian frontier along the River Pruth. Nevertheless, the strategic victory to which the cavalry had contributed its fair share was enormous: Rumania was effectively knocked out of the war; German and Austro-Hungarian forces were released for service on other fronts; and, as in another war one-quarter century later, Germany now enjoyed unfettered access to large reserves of foodstuffs, oil, and other war matériel, including much needed horseflesh.

The enormous haul of goods resulting from the eastern victories of the years 1915 to 1917 was only reinforced in early 1918 by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which the Central Powers (read, Germany) imposed on a Russia already undone by revolution. Whatever else it did, the treaty brought to Germany a seemingly immeasurable area of conquest stretching away to the east and southeast. Included was the bulk of the Black Sea Steppe, while from the newly occupied Ukraine alone “Germany…obtained 140,000 horses during the war.” Bearing in mind that the Ukraine really only fell under German occupation as of March 1918, and that the armistice in France brought the fighting officially to a halt in November, the Germans’ requisition-process was harsh indeed but necessary in any case. General Erich Ludendorff evidently thought so. Remarking on the acquisition of horses in the newly occupied eastern lands and the protection of that resource by German troops, he said pointedly that Germany could not carry on the war on the Western Front without the horses from the Ukraine. Be that as it may, Germany’s armies were nonetheless defeated. However unwillingly, Germany was eventually forced to relinquish all of her conquests and a great deal more once the Allies delivered their own punitive settlement, the Treaty of Versailles.