On the afternoon of 22 April Hitler sent Keitel southwest of the city to give General Walther Wenck and his 12th Army orders to come to the rescue of Berlin and send the Red hordes packing. Keitel met with Wenck the next morning, 23 April, and blustered on at length.

Wenck was a soldier’s soldier, highly professional and a great inspiration to his men, and he knew perfectly well that he had been ordered to lead his men to futile destruction. He shrugged and rearranged the orders to conform to reality: the 12th Army would attack, but it would simply be a rescue operation to help survivors of trapped German forces to the east escape the grasp of the Red Army.

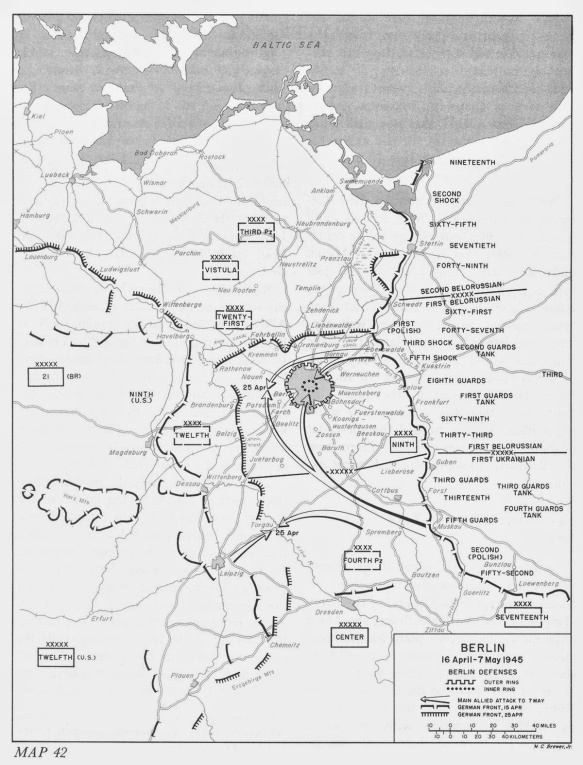

On 24 April, Wenck’s 12th Army to the southwest began its “relief operation”. One of his officers wrote: “Who would have ever thought that it would be just a day’s march from the Western Front to the Eastern Front?” There was no thought of defeating the Red Army, only to do everything that could be reasonably done to reach trapped German civilians and soldiers, and then withdraw west. Wenck hardly bothered to acknowledge most of the orders sent him, though communications and organization were in such a bad state that it wasn’t much trouble to ignore them.

#

In early April, General Walther Wenck, formerly Chief of Staff to General Guderian at the OKH and then briefly Himmler’s Chief of Staff at Army Group Vistula, was called back from convalescent leave for wounds sustained in a February automobile accident to take command of the newly organised 12th Army. He was given a two-part mission. His primary task was to shore up the rapidly receding western front between the armies of Field Marshals Ernst Busch and Albrecht Kesselring, Commanders in Chief North-west and West respectively, now taking a severe beating from the British and North American forces racing eastwards with barely a pause since the landings at Normandy in June 1944. But Hitler had also envisioned a plan whereby Wenck’s 12th Army would launch a massive counter-attack against General Bradley’s 12th Army Group, now making rapid progress toward the Elbe. The idea was to slice a 320km (200 mile) swath straight through General William Simpson’s Ninth Army to the Ruhr pocket, thereby releasing the 300,000 men of Model’s Army Group B and splitting the armies of Montgomery and Bradley. Hitler wanted to achieve this improbable feat by appropriating a Soviet trick. He instructed the officers of the new 12th Army to round up 200 non-descript Volkswagen automobiles and use them to infiltrate the enemy lines and disrupt the rear to effect the breakthrough.

Even if the plan had been realistic when formu- lated, it never got the chance to be tested: the front was moving too rapidly eastwards. Indeed, Wenck had some trouble catching up with his new head- quarters as it continually retreated to the East. He received a rude shock, and a quick education in the reality of the military situation when, on his way to assuming his new command, he attempted to stop in his hometown of Weimar to withdraw his family’s savings from the bank: American tanks from General George S. Patton’s Third Army were already there. Within two days of Hitler’s elaboration of his plan, on 13 April, the Allies succeeded in cutting Model’s forces in the Ruhr pocket in two and capturing the eastern half. Model had already told his troops that he was dissolving Army Group B on his own authority to save them the humiliation of surrender; it was left to each man whether to surrender individually, continue fighting, or attempt to make his way home through the Allied lines.

Wenck finally caught up with his headquarters near Rosslau, some 75km (46 miles) south-west of Berlin. Positioned along a 200km (125 miles) front from Wittenberge down the River Elbe to Leipzig, the 12th Army was supposed to have been made up of 10 divisions, some 200,000 soldiers, composed of Panzer Training Corps officers, cadets, Volkssturmer, and the remains of 11th Army, which had been involved in some ferocious fighting in the Harz mountains. But much of Wenck’s army, he quickly discovered, existed only on paper. Some of the units were still in the process of being organised but, at most, he had at his disposal roughly five and a half divisions, with 55,000 men. These were equipped with a few self-propelled guns, about 40 personnel carriers, and a number of fixed artillery positions at bridges and around cities like Magdeburg. The outlook was not encouraging. But the situation through- out what remained of the Reich was bleak, and Wenck, the Wehrmacht’s youngest general, faced it with surprising vigour and imagination. Determined to hold the Western Allies at the Elbe for as long as possible, while at the same time freeing up as many men as possible to help shield Berlin from the Soviets, he intended to use the most experienced of the 12th’s few and green forces as a sort of mobile shock troop, shuttling them from crisis to crisis. To this end he positioned his best forces in Magdeburg and other centrally located urban centres.

Wenck’s instincts for focusing on the cities were sound, though it didn’t require too much military genius to understand that this last stage of the war would be fought predominantly in large, urban areas. There had been some significant city battles fought already in this war, most notably in Stalingrad and Warsaw. But for the most part it had been a war of large-scale, mobile operations conducted in open terrain or before cites; the kind of warfare best suited to the era’s fascination with tanks and other mobile armour. But in April 1945, on the eve of the war’s final act, with Germany’s room for manoeuvring and building reserves rapidly disappearing, that kind of operational depth was no longer available. Inevitably, particularly given the Allies’ insistence on Germany’s unconditional surrender and Hitler’s inability to consider any kind of retreat or surrender, the final battle would almost certainly have to be fought inside the Third Reich’s capital.

#

To the north of Magdeburg, the US Fifth Armored Division was poised to seize Tangermunde, just over 60km (38 miles) from the western edge of Berlin. To the south, American forces had succeeded in crossing the Elbe at two points. The Second Armored Division had gained Schonebeck, although not before the Germans blew the bridge. Taking Combat Command D, Brigadier General Sidney Hinds managed to force a crossing at nearby Westerhusen, putting three battalions across by the evening of the 12th April and attempting to reinforce the bridgehead via an improvised cable ferry. On the morning of the 14th, however, armoured units of General Wenck’s 12th Army suddenly attacked with ferocious intensity. Wenck’s idea for mobile shock forces proved to be very effective, as his inexperienced but eager soldiers wreaked havoc on the Americans’ newly won positions. With the cable ferry knocked out in one of the first salvoes, the desperate GIs radioed for air support. Few planes were forthcoming, however, as the advance had been so swift that the airstrips had been left too far behind for effective support. By midday, General Hinds ordered a full retreat from the Elbe’s eastern bank, though it took days for all of the survivors to trickle back to the western bank. In the end, 304 men had been lost.

#

On Sunday 22 April OKW Chief of Operations, Colonel General Alfred JodI, offered a suggestion which seemed to pique Hitler’s interest. Convinced that the Americans were not going to advance any further east, JodI suggested that Wenck’s 12th Army, which had been facing them off on the Elbe, could march immediately to Berlin, link up with the Ninth, and at least prevent the complete encirclement of the city. Hitler agreed and dispatched Keitel to the western front. There, just past 0100 hours, with much bluster and waiving of his field marshal’s baton, Keitel ordered Wenck to leave his position on the Elbe and push with all speed towards Potsdam.

#

Soviet Marshal Konev was now particularly worried about Wenck’s 12th Army and the increasing pressure on the south-west sector, Treuenbrietzen. On 24 April, the same day that the ‘Garlitz Group’ was success- fully beaten back on the southern flank, Panzers from 12th Army’s 41st and 48th Panzer Corps smashed into the thinly stretched left flank of Lelyushenko’s Fourth Guards Tank Army. Simultaneously, units of the German 20th Army Corps launched an infantry attack, covered by artillery bombardment, aimed at taking back Treuenbrietzen, 35km (21 miles) south of Potsdam. The attack continued throughout the day and was repeated at night. The Soviets managed to hold their lines, however. Fighting with fierce determination, the 10th Guards Mechanised Brigade holding the town allowed the German troops to advance very close, and then opened up with heavy machine-guns, mowing the Germans down, while hidden tanks roared out of their ambushes and crushed the foot-soldiers underneath their treads. Responding to the armoured attack on Fourth Guards Tank’s flank, meanwhile, Yermakov’s Fifth Guards Mechanised Corps established a mobile anti-tank reserve unit from 51st Guards Tank Regiment and set up a number of fixed anti-tank positions and tank or artillery ambush sites. Yermakov also mobilised the Soviet PoWs just liberated from German concentration camps, issuing them with captured Panzerfausts and organising them into teams of 10-25 men in anti- tank strong-points.

The next morning, two German divisions supported by the 243rd Assault Gun Regiment again attacked the 10th Mechanised Brigade’s positions in Treuenbrietzen, while a separate attack was launched against the nearby Beelitz-Buchholz sector. Again, the Germans were held off, this time with the support of First Guards Ground-Attack Air Corps, which streaked out at low altitude and dumped anti- tank bombs on the Germans. With the arrival of 147th Rifle Division from the 102nd Rifle Corps (13th Army) and the 15th Rifle Regiment, the semi-encirclement of Treuenbrietzen was broken and the Soviets’ lines secured.

By 25 April Wenck was making no serious effort to reach Berlin, and certainly not to save Hitler.

On the city’s south-west side, the Potsdam garrison had fallen to Lelyushenko’s tanks on 27 April, and he was now pressing 10th Guards Tank Corps and 350th Rifle Division (from 13th Army) on towards the heavily manned ‘Wannsee Island’. The attack continued throughout the day, but without any significant progress. Meanwhile, as Sixth Mechanised Corps followed Lelyushenko’s orders to race further west to Brandenburg to cut off the potential escape route, they suddenly slammed into Wenck’s 12th Army. Although Wenck, it seems, was in no rush to push his way too far into the Soviet forces, he quickly launched further attacks into the Treuenbrietzen sector, leaving Lelyushenko’s left flank in an extremely difficult position, caught in a reversed front by Wenck’s forces to the west and the Ninth in the east.

#

The end of the battle for Berlin did not immediately mean an end to the war, although it could continue afterwards only in a disorganised, obviously futile manner. For most of the German units maintaining some form of military discipline and cohesion, their only thought was to get to the Elbe and surrender to the Americans or British. This was the case for the last formations to survive the battle for Berlin; Busse’s Ninth Army and Wenck’s 12th. For days, the Ninth had been fighting desperately to reach Wenck to the south-west of Berlin, and so gain an avenue to the Elbe. The First Ukrainian Front’s main concern was to take Berlin’s central district, rather than block the Ninth’s escape, but the fighting was still difficult, and made more so by the Ninth’s precarious supply situation; there was almost no ammunition left, and few weapons, and hundreds of civilian refugees had joined their columns. On 1 May, down to their last tank, Busse’s men were pushing forward with all they had, when they heard firing coming from behind the Soviets, who started breaking. Lieutenant General Wolf Hagemann leapt out of his tank with the only weapon available, a shotgun, and began pumping shells at the Soviets. Within minutes, the Ninth Army made contact with the 12th Army; of their original 200,000 men, 40,000 had survived. Generals Busse and Wenck, exhausted and filthy, walked silently up to each other and shook hands. By 7 May, both armies had made it to the Elbe and surrendered to the Allies.

The 12th Army was reconstituted on the Western Front near the Elbe River on April 10, 1945.

Twelfth Army

General of Panzer Walther Wenck

XX Corps – General of Cavalry Carl-Erik Koehler

Theodor Körner RAD Infantry Division

Ulrich von Hutten Infantry Division

Ferdinand von Schill Infantry Division

Scharnhorst Infantry Division

XXXIX Panzer Corps – Lt. Gen. Karl Arndt

(12 – 21 April 1945 under OKW with the following structure)

Clausewitz Panzer Division

Schlageter RAD Division

84th Infantry Division

(21 – 26 April 1945 under 12th Army with the following structure)

Clausewitz Panzer Division

84th Infantry Division

Hamburg Reserve Infantry Division

Meyer Infantry Division

XXXXI Panzer Corps – Lt. Gen. Rudolf Holste

Von Hake Infantry Division

199th Infantry Division

V-Weapons Infantry Division

XLVIII Panzer Corps – General of Panzer Maximilian von Edelsheim

14th Flak Division

Kampfgruppe Leipzig

Kampfgruppe Halle