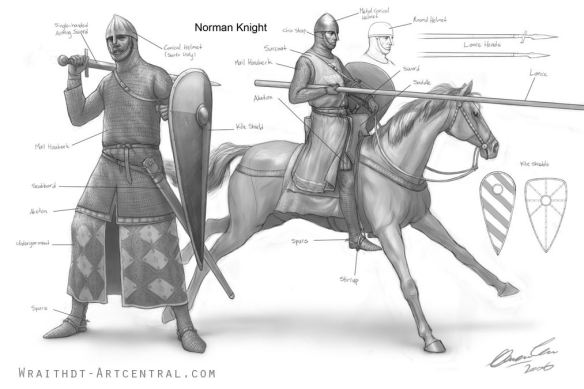

A Norman knight. The raised pommel forward and rear increased stability in the saddle and the kite shaped shield gave added protection to his exposed legs. The Saxons were not familiar with fighting armoured horsemen.

Norman battle tactics were as unfamiliar to the English as their close-cropped appearance and language. Chronicler William of Malmsbury described the differences between the assailants on that `fatal day’.

`The English at the time wore short garments, reaching to the mid knee; they had their hair cropped, their beards shaven, their arms laden with gold bracelets, their skin adorned with punctured designs; they were wont to eat until they became surfeited and to drink until they were sick’.

The Normans were arrayed in a strange battle formation. There were three divisions of three lines, with the Bretons to the left, Flemish and French on the right and William’s men in the centre. Some 1,500 archers were positioned ahead of 4,000 heavy infantry with 2,000 knights waiting expectantly in the rear for the first signs of a breach in the shield wall. William of Malmsbury described the Normans as `exceedingly particular in their dress’ and `fierce in attacking their enemies’. Unlike the solid formation ahead of them, the Normans were `ready to use guile or to corrupt by bribery’. They were accessible to new ideas and fought as such, `they weigh treason by its chance of success, and change their opinions for money’. This was a clash of two cultures.

William’s men were independent-minded adventurers, like their Viking forefathers. They fought for plunder and economic gain as well as for their lords. Buoyed by Papal support and the promise of power and riches by Duke William all the soldiers had participated in a high-risk enterprise. By crossing the Channel, a perilous voyage in questionable weather, they had burned their boats. Going back was hardly an option. They were a disciplined force, as evidenced by William’s masterful logistics and tight control. He mustered a force of 10,000 to 14,000 men and kept them intact and focussed throughout a long summer in the Dives and Somme estuaries prior to the crossing. The biggest and riskiest amphibious operation mounted since Roman times paid off, the landings were unexpectedly unopposed. William’s landing force was an inter-ethnic mix of about 2,000 Bretons, 1,500 Flemings and French and 4,000 Normans. More diverse than the English, but unlike them, the majority were hardened professionals, mercenaries and accordingly equipped.

Two weeks of rapine and plunder in the surrounding English villages followed the months of enforced inactivity in France, a deliberate policy to goad Harold into battle. After the disciplined restrictions placed on their sojourn in the Dives estuary awaiting favourable winds, unrestricted warfare against defenceless civilians had been welcomed by warriors used to raiding back home, especially as it formed part of God’s will. With so little opposition to date, William’s men probably felt confident they would give the effeminate English a beating. They had not even appeared to defend the helpless villages they razed to the ground, and after this battle there would be even more.

Armoured horsemen had been gaining steadily in importance on the Continent but were less well known in England. Norman knights were identically armed and clad like the Housecarls and Thegns although knights wore knee-length mail hauberks, split front and rear for riding with an integral mail hood. Helmets could be hammered from a single piece of iron or made of riveted segments, padded within with leather or cloth to cushion the head against blows. These conical helmets often had a nasal guard to protect the nose and face, giving the wearer a grim impersonal appearance, which could be embossed and decorated to add to the wearer’s fierceness.

The Norman archers failed to make an appreciable indentation on the Saxon shield wall, because flights loosed uphill tended to stick in shields or go overhead. The Bayeux Tapestry shows axe and sword wielding Housecarls with clusters of arrows protruding from their shields. Cross-bows were employed at close ranges and these men, like the archers, occupied the lowliest social position in William’s army. Hideous wounds caused by cross-bow quarrels against the unprotected Fyrd apparently caused real dismay in the depth of the English shield wall. It soon became apparent to the Normans that the only way to break through would be by direct attacks by mounted knights.

Norman war horses were carefully selected and bred stallions, taught to head-butt as well as kick and bite. They caused real consternation as the ground shook with their up canters against the shield lined hill-crest. Half a ton of horse and armoured rider could conceivably barge a breach in the shield wall, but horses shy away from seemingly solid objects. Attempting to simply push through, despite losing momentum invited the sort of retribution described by Robert Wace, as one Housecarl:

`.Rushed straight upon a Norman knight who was armed and riding on a warhorse, and tried with his hatchet of steel to cleave his helmet; but the blow miscarried, and the sharp blade glanced down before the saddle-bow, driving through the horse’s neck to the ground, so that both horse and master fell together to earth’.

Once down at the edge of the shield wall he was finished. The Bayeux Tapestry suggests the Norman knights were jabbing their lances over the top at those behind, riding by, especially vulnerable to being unhorsed by a whirling axe. Slowed down by the climb, stumbling horses were pushed away from the pliant shield wall, acting like an aggressive rugby scrum. Examination of surviving skeletons from the period reveals that most injuries appear to have been inflicted to the upper head and shoulder and lower pelvic region. Skull indentations suggest many fighters had no head protection at all. Injuries to the upper leg and pelvic region point to the common fighting practice of disabling with a spear thrust and then finishing off the victim as he tumbled to the ground, with a sword or axe blow to the head.

The Normans were raiders, adept at swift mobile cavalry sweeps. Once elements of the Fyrd had been enticed beyond the shield wall by feigned retreats or cut off in groups, they were easy meat for the Norman horsemen. This mounted element and the employment of archers in support gave the Normans a greater degree of flexibility to whittle down the more immobile shield wall. Williams mounted command capability gave him an edge in this very tight contest between two evenly matched, tactically astute and ruthless warlords. It was a close run battle, lost with the fall of key commanders at crisis points. The Normans ventured all, planned cogently and won.