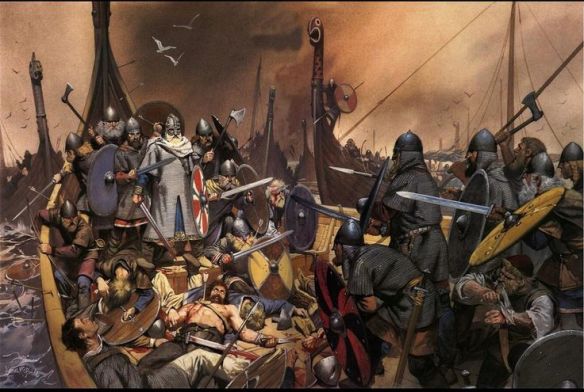

The tale of the battle of Svöldr mentions one Einar Tambarskelve, who stood beside King Olaf Tryggvasson. After he had narrowly missed Eric Haakonsson, a leader of the enemy, his bow was broken by an arrow hit. Olaf asked him what had burst with such a noise: he replied, “It was Norway, Sire, that sprang from your hands.” King Olaf Tryggvason,s last stand. Battle of Svolder, 999 or 1000. Painting by Angus Mcbride

The Battle of Svolder (Svold, Swold) was a naval battle fought in September 999 or 1000 in the western Baltic Sea between King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway and an alliance of his enemies. The backdrop of the battle was the unification of Norway into a single state, long-standing Danish efforts to gain control of the country, and the spread of Christianity in Scandinavia.

The sea battles of the Vikings were fought according to the same principles as battles on land. Each side roped most of their ships together side by side to make a platform on which to form a shield wall. The attackers tried to storm this platform, as e. g. in the battles of Hafrsfjord in 872, Svöldr in 1000 and Nissa in 1062. Ship after ship was taken and then detached from the formation to drift away. Both fleets used to keep some ships outside the formation to manoeuver; these were used to attack the enemy by going alongside and boarding, in a hailstorm of arrows, stones and spears from both sides. If the defenders succeeded in killing the attacking rowers, or if the oars of the attacking ship were broken, the attack often failed through inability to manoeuver. However, the elements of a real naval battle of the Classical age – outmanoeuvering, ramming, forcing the opponent to sail against the wind, or the use of catapults – were unknown among the Vikings. Most sea battles took place in quiet coastal waters or river mouths, where there was no space for such tactics.

When fighting amongst themselves, the Vikings’ major battles almost invariably took place at sea- witness Hafrs Fjord in 872, Svöldr in 1000 and Nissa in 1062, to cite but three examples. Nevertheless, they made every effort to ensure that a naval action was as much like a land battle as possible, arranging their fleets in lines or wedges; one side-or sometimes both-customarily roped together the largest of their ships gunwale to gunwale to form large, floating platforms. The biggest and best-manned ships usually formed the middle part of the line, with the commander’s vessel invariably positioned in the very centre, since he normally had the largest vessel of all. High-sided merchantmen were sometimes positioned on the flanks of the line too. The prows of the longer ships extended out in front of the battle-line and some of them, called bardi, were therefore armoured with iron plates at stem and stern, which bore the brunt of the fighting. Some even had a series of iron spikes called a beard (skegg) round the prow, designed to hole enemy ships venturing close enough to board.

In addition to this floating platform there were usually a number of additional individual ships positioned on the flanks and in the rear, whose tasks were to skirmish with their opposite numbers; to attack the enemy platform if he had one; to put reinforcements aboard their own platform when necessary; and to pursue the enemy in flight. Masts were lowered in battle, and all movement was by oar, so the loss of a ship’s oars in collision with another vessel effectively crippled it. Nevertheless, the classical diekplus manoeuvre, which involved shearing off an enemy vessel’s oars with the prow of one’s own ship, does not seem to have been deliberately employed, and nor was ramming.

The main naval tactic was simply to row against an enemy ship, grapple and board it, and clear it with hand weapons before moving on to another vessel, sometimes cutting the cleared ship loose if it formed the wing of a platform. The platforms were attacked by as many ships as could pull alongside. Boarding was usually preceded by a shower of arrows and, at closer range, javelins, iron-shod stakes and stones, as a result of which each oarsman was often protected by a second man, who deflected missiles with his shield. On the final approach prior to boarding, shields were held overhead ‘so closely that no part of their holders was left uncovered’. Some ships carried extra supplies of stones and other missiles. Stones are extensively recorded in accounts of Viking naval battles, and were clearly the favourite form of missile. The largest were dropped from high-sided vessels on to (and even through) the decks of ships which drew alongside to board.

OLAF I, TRYGGVASON, KING OF NORWAY (c. 964-1000)

King from 995, probably brought up in Russia after the killing of his father. He took part in raids in the Baltic and on expeditions to England. He was probably the victor of Maldon in 991. He allied with Sweyn Forkbeard. Olaf converted to Christianity in England, promising not to return. He overthrew Hakon to become King of Norway, encouraging the conversion of Norway and Iceland. He was killed at Svöld, fighting an alliance of Danes and Swedes. It was said that, recognising defeat, he leaped from his ship the Long Serpent (the largest ship recorded in the sagas) and drowned. Olaf Tryggvason’s Saga is part of the Heimskringla. There were tales that he survived.

SWEYN I HAROLDSSON (FORKBEARD), KING OF DENMARK (d. 1014)

King from 987, son of Harold Bluetooth from whom he seized the Danish throne. He led raids against England in 991 and 994 with Olaf Tryggvason. He opposed his former comrade in Norway. Sweyn’s ally, Jarl Erik of Lade, defeated Olaf at Svöld in 1000. As king Sweyn took over Hedeby and dominated the Wends. He led expeditions to England in 1003 and 1006. In 1013 he came to defeat Aethelred II, who fled. He controlled England but died in February 1014 at Gainsborough in Lincolnshire. In Denmark his son Harold succeeded but his most famous son was Cnut the Great.