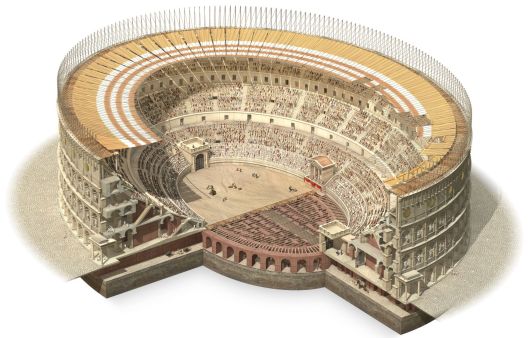

Artist’s rendering of the Colosseum during a naumachiae. The Water Battles at the Colosseum were documented by Ancient Roman writers who recorded that the Colosseum was used for naumachiae (the Greek word for sea warfare) or simulated sea battles.

The greatest structure erected during the age of the Flavian emperors (69-96 A.D.) and arguably the finest architectural achievement in the history of the Roman Empire. The Colosseum was originally called the Flavian Amphitheater, but it became known as the Colosseum after a colossal statue of Nero that once stood nearby. Its origins are to be found in the desire of the Emperor VESPASIAN to create for the Romans a stadium of such magnitude as to convince both them and the world of Rome’s return to unquestioned power after the bitter civil war.

Construction began in 72 or 75 A.D. Vespasian chose as the site a large plot between the Caelian and Esquiline hills, near the lake of Stagnum Neronis and the GOLDEN HOUSE OF NERO. His intent was obvious – to transform the old residence of the despot Nero into a public place of joy and entertainment. He succeeded admirably, and his achievement would be supplemented in time by the Baths of Titus, built in order to use up the rest of the Golden House. The work proceeded feverishly and the tale that 30,000 Jews were pressed into service persists. Yet Vespasian did not live to see its completion. Titus took up the task in his reign, but it was Domitian who completed the structure sometime around 81 A.D. The official opening, however, was held on a festal day in 80. Titus presided over the ceremonies, which were followed by a prolonged gladiatorial show lasting for 100 days.

The Colosseum seated at least 45,000 to 55,000 people. Vespasian chose an elliptical shape in honor of the amphitheater of Curio, but this one was larger. There were three principal arcades, the intervals of which were filled with arched corridors, staircases, supporting substructures and finally the seats. Travertine stone was used throughout, although some brick, pumice and concrete proved effective in construction. The stones came from Albulae near Tivoli. The elliptically shaped walls were 620 feet by 507 feet wide at their long and short axes, the outer walls standing 157 feet high. The arena floor stretched 290 feet by 180 feet at its two axes. The dimensions of the Colosseum have changed slightly over the years, as war and disaster took their toll. Eighty arches opened onto the stands, and the columns employed throughout represented the various orders – Doric, Ionic and Corinthian – while the fourth story, the top floor, was set with Corinthian pilasters, installed with iron to hold them securely in place.

The seats were arranged in four different sections on the podium. The bottom seats belonged to the tribunes, senators and members of the Equestrian Order. The second and third sections were for the general citizenry and the lower classes, respectively. The final rows, near the upper arches, were used by the lower classes and many women. All of these public zones bore the name maeniana. Spectators in the upper seats saw clearly not only the games but were shaded by the velaria as well, awnings stretched across the exposed areas of the stadium to cover the public from the sun. The canvas and ropes were the responsibility of a large group of sailors from Misenum, stationed permanently in Rome for this sole purpose.

Every arch had a number corresponding to the tickets issued, and each ticket specifically listed the entrance, row and number of the seat belonging to the holder for that day. There were a number of restricted or specific entrances. Imperial spectators could enter and be escorted to their own box, although Commodus made himself Can underground passage. Routinely, the excited fans took their seats very early in the morning and stayed throughout the day.

The stories told of the games and of the ingenious tricks used to enhance the performances and to entertain the mobs could rarely exaggerate the truth. Two of the most interesting events were the animal spectacles and the famed staged sea battles of Titus, both requiring special architectural devices. In the animal spectacles the cages were arranged so expertly that large groups of beasts could be led directly into the arena. Domitian added to the sublevels of the arena, putting in rooms and hinged trapdoors that allowed for changes of scenery and the logistical requirements of the various displays. As for the sea fights, while Suetonius reports that they were held instead in the artificial lake of Naumachia and not in the amphitheater, Die’s account disagrees. The Colosseum did contain drains for the production of such naval shows, although they were not installed until the reign of Domitian. The abundance of water nearby made the filling of the Colosseum possible, although architecturally stressful. The drains routinely became clogged, causing extensive rot in the surrounding wood. The year 248 A. D. saw the last recorded, sea-oriented spectacle called a naumachia.

A number of other practical features were designed for the comfort of the thousands of spectators. Spouts could send out cool and scented streams of water on hot days, and vomitoria (oversized doors) were found at convenient spots for use by those wishing to relieve themselves of heavy foods. Aside from the statues adorning the arches, the Colosseum was solid, thick and as sturdy as the Empire liked to fancy itself. The structure was Vespasian’s gift to the Romans, whose common saying remains to this day: “When the Colosseum falls, so falls Rome and all the world.”

Although the Colosseum is the most famous Roman amphitheater, nearly 200 others survive archaeologically throughout the former Roman Empire, mostly in its western provinces. Factors of urban topography or available building materials create variations and regional groupings among surviving amphitheaters. Architects in Britain and other northern provinces used turf-and-timber construction – but this cheaper construction material did not lessen the building’s status as a prestige project or a symbol of connection to Rome. Specialized structures to control wild animals appear only in North Africa and sites on the shipping routes from North Africa to Rome, not in the rest of the empire. Thus, the amphitheaters at Capua and Pozzuoli (south of Rome) have extensive subterranean passages and other features for handling animals, while the equally luxurious amphitheaters at Arles and Nîmes do not. In the east, there was less need for purpose-built gladiatorial structures since preexisting theaters and stadia could be adapted to the same purpose. Once again, eastern and western provinces show different forms of adaptation to Roman rule.