The inconclusive, unpredictable, and expensive nature of large campaigns, low-level border conflicts and raids (kleinkrieg) gained importance and became the essential part of the battle environment and lifestyle of the Ottoman-Habsburg frontier after the long reign of Süleyman. This situation was exaggerated by frontier populations, which consisted of thousands of mercenaries who sought employment through war. Within certain limits both sides tolerated these raids and conflicts within. Occasionally, events spiraled out of control, however, provoking large campaigns. The Long War (Langekrieg) of 1593 to 1606 was a good example of this type of escalation. In 1592, the governor of Bosnia, Telli Hasan Pasha, increased the level of raids and began to conduct medium-sized attacks against specific targets by using his provincial units only, although he probably had the tacit support of some high-ranking government officials. Initially, he achieved a series of successes but suffered a decisive defeat near Sisak in which nearly all his army was wiped out and he himself was killed. The new Grand Vizier, Koca Sinan Pasha, used this incident as well as a popular mood inclined toward war to break the long peace.

The ambitious Sinan Pasha began the war eagerly but did not show the same enthusiasm during the actual start of the military campaign. The army mobilization was very slow and haphazard after long decades of inaction on the western frontier and from the repercussions of the draining and tiring Iranian campaign. Consequently, the campaign season of 1593 was wasted, and real combat activity only began in 1594 when the Ottomans easily captured Raab (Yanik) and Papa. However, a joint revolt and defection of the Danubean principalities of Wallachia, Moldovia, and Transylvania negated these gains and put the army in the very difficult position of facing two fronts at the same time. Moreover, the revolt threatened the security of the Danube River communications, which was essential for the supply of the army. The Wallachian campaign of 1595 to suppress the revolt ended with a humiliating defeat and huge loss of life. In the meantime, Habsburg forces captured the strategic fortress of Gran (Estergon).

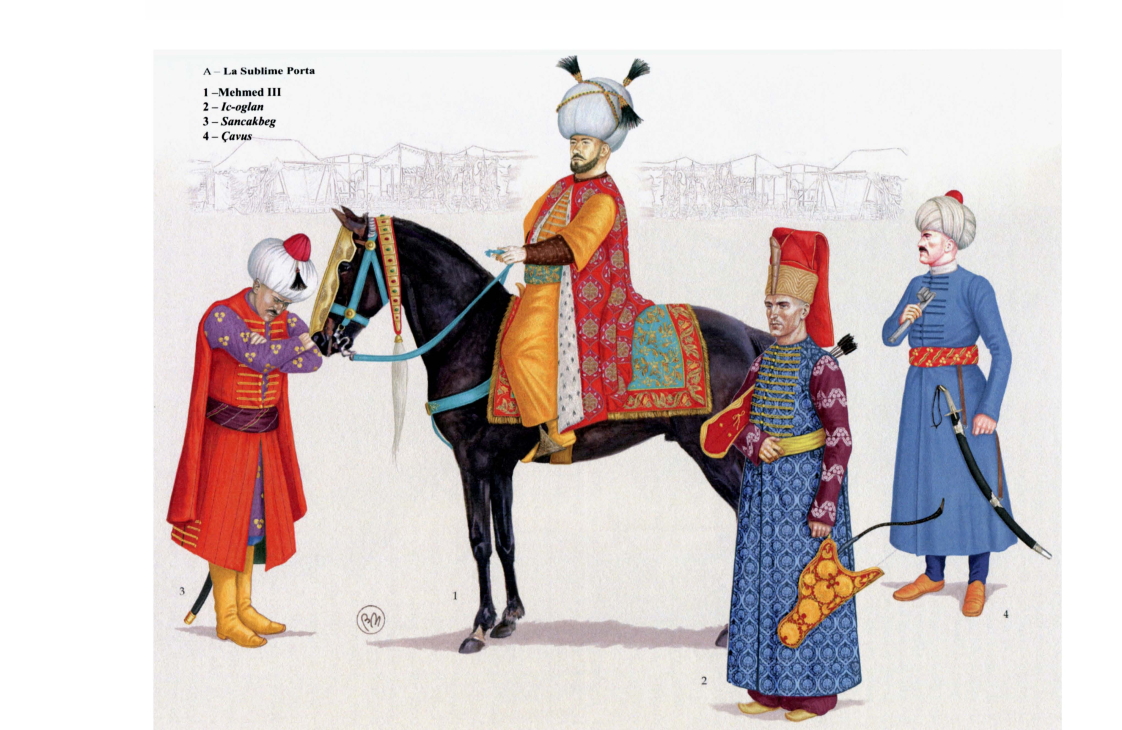

The ever-resourceful Ottoman government immediately reacted to the consequences of these disasters, which had damaged especially the morale and motivation of the standing army corps. A new campaign was organized, and the reluctant sultan, Mehmed III, was persuaded to lead the expeditionary force in person. The presence of the sultan gave a big boost to army morale, and it advanced to the main objective, the modern fortress of Eger (Eğri), in good order. The Ottomans demonstrated their pragmatism and receptivity once again by applying the same effective siege artillery tactics that their Habsburg enemies had used against Estergon, and Egğri capitulated on October 12, 1596.

After the successful resolution of the siege, the Ottoman army had to face the relief force. Initially the Ottoman high command underestimated the danger and sent only the vanguard to deal with them. After the defeat and retreat of the vanguard, however, it decided to advance and attack the enemy with the entire army. The Habsburg army was deployed mainly in well-fortified defensive wagenburgen formations and it controlled all the passes in the swampy region of Mezökeresztes (Haçova). Even though captured prisoners had revealed the enemy strength and intentions two days before, the Ottoman high command insisted on an offensive strategy after spending only a single day passing through the swamps and thereafter deploying immediately into combat formation. The entire Ottoman first line joined the assault on October 26. The daring Ottoman plan failed, the assaulting units were stopped by massive firepower, and were then routed by Habsburg counterattacks. Fortunately, the Habsburg units gave up pursuit to loot the Ottoman camp. The day was saved at the very last moment with the daring counterattack of auxiliary units and cavalry against the Habsburg flanks and rear. As the disorganized and looting Habsburg soldiers panicked, the retreating Ottoman units immediately turned around and joined the auxiliary units. The Habsburg army suffered huge casualties in the following mayhem, and the Tatars decimated the remainder during the pursuit.

The Ottoman high command ended the campaign and returned to winter quarters instead of exploiting the advantage gained by these two victories. The reason was understandable considering the command elements of the army in this campaign. Except for a few operational level commanders, none of the military or civilian members of the high command (including the sultan) had the knowledge, experience, or courage to lead the army forward. This failure is contrasted by the strong performance of the standing army corps and provincial units, which executed their combat tasks properly and in some cases better than in previous campaigns. The Habsburg side also had the same leadership problems as well as other structural problems, such as mercenaries and the conflicting interests of regional magnates. The outcome of this mutually inarticulate strategic vision was to drag the war out into a series of seasonal campaigns launched against each others’ fortresses.

The Long War continued on for 10 more years, during which both armies, the Habsburgs especially, avoided large-scale battles. Because of the unpredictability of the outcome of pitched battles, both sides focused more on smaller battles revolving around key fortresses. After the disastrous year of 1598 in which Yanik was lost and the Ottoman army suffered numerous difficulties caused by harsh weather, the balance began to tip to the advantage of the Ottomans. Repeated attempts by the Habsburgs to capture Buda (Budin), the capital of Ottoman Hungary, failed whereas the Ottomans captured the mighty fortress of Kanisza (Kanije) and managed to keep it against all odds. The rebellious Danubean principalities, likewise, could not withstand the sheer weight of the war and one by one gave up. An unexpected revolt of the Transylvanians against the Habsburgs effectively wiped out the remaining chances of Habsburg success, while the Ottomans reconquered strategic Estergon. Once again, however, the Ottomans were unable to exploit their success effectively. This time it had nothing to do with the government or the strategic direction of the war but, rather, because of the collapse of the eastern frontier defensive system against a new Safavid offensive and the immediate security threat of renewed popular revolts (Celali). The Long War concluded with the Zsitvatorok peace agreement of 1606, which itself was the outcome of mutual exhaustion and other urgent issues.

Even though the Ottoman government failed to achieve a complete victory in the Long War it still gained considerable advantage by retaining such critical territorial conquests as Kanije and Eğri. This forced the Habsburgs to spend large amounts of money and time to build up a new defensive line against the Ottomans. Another advantage occurred with the influx of large numbers of western mercenaries, who introduced new weapon systems, tactics, and techniques into the Ottoman military. The Ottoman military benefited greatly from these new innovations, thanks to its receptivity and pragmatism. For the first time in Ottoman history, the government enlisted groups of mercenaries who had deserted from the Habsburg camp. The most well-known example involved the desertion of a French mercenary unit in the Papa fortress to the Ottoman side on August 1600. Afterwards, they served on various campaigns during the Long War, and some of them continued to serve well after the end of war. Even though this was extraordinary and not representative of a generalized trend, it demonstrates that the Ottoman government of the seventeenth century was far from being the reactionary and conservative organ that is still a commonly held conviction about its identity today.

Moreover, the length and difficulty of the war forced the Ottoman military to the limits of its capabilities and drastically transformed it. In order to meet the requirements of war, the Ottoman government had to reorganize the empire’s financial system and to recruit or mobilize all available manpower. The obvious outcome of the financial reorganization and enlargement of eligible population groups to the privileged Askeri class not only changed the face of the military but also had a huge impact on Ottoman society as a whole. Moreover, the increased need for musketeers further weakened the traditional military classes, especially the Sipahis and other cavalry corps.

From every aspect, the Ottoman military ended the war with a completely different army. Instead of mounted archers in loose formations, the army employed infantry with firearms in deep formations of several rows of men. Instead of a regionally based provincial army, a salary-based standing army supported by provincial mercenaries became the dominant military organization. Moreover, that army was becoming highly evolved as an institution that had formalized ranks, corps of specialists, training, and battlefield flexibility. Therefore, it can be safely said that the classical period of the Ottoman military effectively ended with the signing of the Zsitvatorok agreement on November 11, 1606.