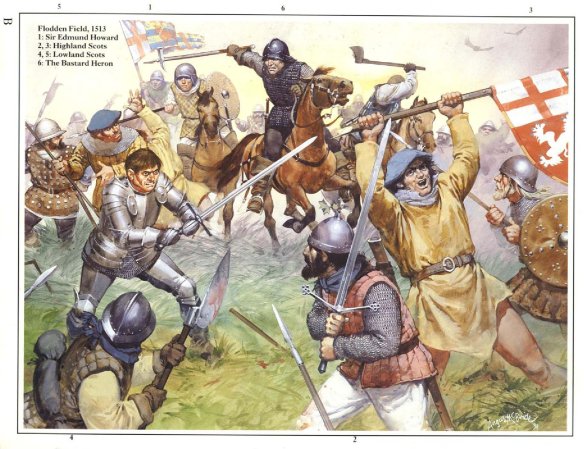

Scottish soldiers at the Battle of Flodden Field (9 Sep 1513)

The Lancashire Bowman.

The longbow was to go out of military fashion in a blaze of glory, to achieve a victory in the old classical style so that it left a glow in the hearts of the yeoman of England, but no pangs of regret in the hearts of his enemies.

The events which led to the Scottish invasion of England in 1513 need not be recapitulated; suffice to say that King James IV of Scotland had crossed the border in mid-August of that year with, for that time, an enormous army of 40,000 men. They were well furnished with the latest artillery of the day. His leaders were all those of the highest rank in the Scottish kingdom; it may be fairly said that no grown-up member of any family of position was absent from the expedition. After some initial skirmishing, the Scots had Northumberland at their mercy; but after taking the castle of Ford, stronghold of the Heron family, James loitered in the neighbourhood whilst his army daily grew less in numbers. Said to have been infatuated by the captured Lady Heron, King James appeared to be regardless of the increasing desertions of those gorged with plunder in addition to those starved through the land being foraged-out. Finally, his army numbered less than 30,000, but those that were left represented the cream of the whole and were claimed to have been one of the noblest bodies of fighting men ever gathered together. To back them, James had a most efficient train of thirty pieces of artillery which had been cast for him at Edinburgh by the master gunner, Robert Borthwick.

Against the Scots was sent the veteran Earl of Surrey, over seventy years of age, and forced, on account of his rheumatism, to travel mostly by coach. Chiefly from the northern counties, he hastily gathered together an army of between 20,000 and 26,000 men. Whilst encamped at Alnwick, Surrey sent a formal challenge to King James, naming Friday, 9th September, as the day of battle; the challenge was duly accepted in the most formal manner. At the time of acceptance, James was encamped in the low ground and, according to the old rules of chivalry, his acceptance from this spot implied that he would give battle on that site. But before long James had moved his camp from there to Flodden Hill, an eminence lying due south of Ford Castle, running east and west in a low ridge. Here, on the steep brow of Flodden Edge, in the angle between the Till and its small tributary, the Glen, James’s defensive position was so strong that no sane foe would dare to attack it.

Realising this, Surrey sent James a letter of reproach in which he pointed out that the arrangement had been made for a pitched battle, and instead James had installed himself in a fortified camp. He concluded by challenging him to come down on the appointed day and fight on Millfield Plain, a level tract south of Flodden Hill. King James refused even to see the herald who brought the message.

Surrey then marched his army up the river Till; put his vanguard with the artillery and heavy baggage across at the Twizel bridge, whilst the remainder of his force crossed at Sandyford, half a mile higher up. Now was presented to James an excellent opportunity of attacking the English whilst they were split into two parts. By failing to grasp it, James now found his foes placed between himself and Scotland; he was left with little alternative but to reverse his order of battle. Setting fire to the rude huts that his men had constructed on the summit of the hill, he moved his force on to Branxton Hill, immediately behind Flodden Edge; the movement was partially obscured from the English by the clouds of smoke that trailed over the brow of the hill. As they formed up on the ridge above Branxton, the Scottish army that had faced south were now drawn up facing north.

The two armies faced each other, both formed into four divisions and both with a reserve. Beginning on the English right, the first division was commanded by Sir Edmund Howard, the younger son of the Earl of Surrey; opposed to him were the Gordons under the Earl of Huntley and the men of the border under the Earl of Home. The second English division was led by Admiral Howard, who was faced by the Earls of Crawford and Montrose. The Earl of Surrey, with the third division, was opposed by King James himself; while Sir Edward Stanley, with the fourth division, had to try conclusions with the Earls of Lennox and Argyle, whose troops were mainly highlanders. The English reserve, mainly cavalry, was commanded by Lord Dacre; that of the Scottish under Bothwell.

It was not until four o’clock that the battle commenced. Then, as an old chronicler says: ‘Out burst the ordnance with fire, flame and a hideous noise… .’ The Scottish artillery was far superior in construction to the English, which was constructed of hoops and bars, whilst the Scots master gunner had cast his weapons; there were, however, more English guns. It seems as though the English gunners were superior to those serving the Scottish cannon, the latter committing the error of firing at too great an elevation so that their shots passed over the heads of the English and buried themselves in the marshy ground beyond. The old writer goes on to say: ‘… and the master gunner of the English slew the master gunner of the Scots, and beat all his men from their guns.’ The early death of Borthwick, brought down by a ball, set up a panic in his men, who ran from their guns – but it was not by artillery fire that Flodden was to be won or lost. James realised this fact and ordered an attack; the border troops of the Lords Huntley and Home appear to have been the first to come to close quarters with the English.

In an unusual silence the Scots rushed forward, their twelve-foot-long pikes levelled in front of them; the initial impetus of their onslaught carried them far into the English lines, so that at first they achieved absolute success. The English right, under Sir Edmund Howard, was thrust back, their leader thrice beaten down and his banner overturned. The English fighting line was in disorder on this flank. Some Cheshire archers, who had been separated from their corps and sent out to strengthen the right wing, fled in all directions and chaos came to Howard’s wing. John Heron, usually known as the Bastard Heron, at the head of a group of Northumbrians, checked the rout long enough for Dacre to charge down with his reserve. This committing of the reserve at such an early stage did not succeed in restoring the English line, but it did put Huntley to flight, whilst the undisciplined borderers of Home had no further idea of fighting. In a border foray, no more was expected after routing one’s opponents; Home’s men did not grasp that Flodden was no ordinary foray – ’We have fought and won, let the rest do their part as well as we!’ was their answer to those trying to rally them.

Whilst this was going on, Crawford and Montrose were furiously attacking the division of Admiral Howard; so much so that the Admiral sent to his father, the Earl of Surrey, for assistance. But Surrey was fully occupied in holding his own against the division commanded by King James, strengthened by Bothwell, who had brought up the reserve and flung them into the struggle. The battle was now at its height and was being hardly contested all along the line; it seemed, here and there, as though the English halberds were proving more deadly weapons at close quarters than the long Scottish pikes.

On the English left, the archers of Cheshire and Lancashire, under Sir William Molyneaux and Sir Henry Kickley, were pouring volleys of arrows into the tightly packed ranks of the Scottish right, highlanders under the Earls of Lennox and Argyle. Galled by the hail of shafts which spitted their unarmoured bodies, the wild clansmen finally found it to be more than they could bear. Casting aside their targets and uttering wild, fierce yells, they flung themselves forward in a headlong rush, claymore and pole-axe waving furiously in a frenzy of anxiety to bury themselves into English flesh and bone. The bowmen and pikemen were shaken, so tremendous was the initial shock, their bills and swords, which had replaced the bows, reeling and wavering under the onslaught; but discipline prevailed and their formation remained unbroken. The archers on the flanks of the mêlée stood back and poured in volley after volley at close quarters, while the inner line of pikemen and men-at-arms held off the wild highlanders. Their arrows gone, the archers threw down their bows, drew their swords and axes to fling themselves into the fray, both in front and on the flanks. It was a deadly struggle whilst it lasted, but gradually the clansmen gave way, fighting at first, but then, suddenly, in complete rout – both earls died trying to stem the tide.

Stanley pressed forward, won his way up and crowned the ridge. He did not make the error of pursuing from the field the thoroughly broken Scots whom his men had just beaten. Facing about, he charged obliquely downhill to take the Scots divisions of King James and Bothwell in flank. This struggle in the centre, between Surrey and King James, had been proceeding fiercely; the King was fighting on foot like the rest of his division, conspicuous by the richness of his arms and armour. Stanley’s flank attack, coinciding with a similar attack on the other flank by Dacre and Edmund Howard, proved disastrous to the Scots. Hemmed in on all sides, they began to fall by hundreds in the close and deadly mêlée; no quarter was asked by either side and none was given. The blood flowing from the dreadful gashes inflicted by axes, bills and two-handed swords made the ground so slippery that many of the combatants were said to have taken off their boots to gain a surer footing.

As a battle, all was over by now and nothing remained but the slaughter. Surrounded by a solid ring of his knights, James refused to yield until he finally fell, dying with the knights who had formed a human shield around him. He was said to have been mortally wounded by a ball fired by an unknown hand; he had several arrows in his body, a gash in his neck and his left hand was almost severed from his arm. Ten thousand men fell on the Scottish side; to list the slain is almost to catalogue the ancient Scottish nobility. With the exception of the heads of families who were too old or too young to fight, there was hardly a family of top rank that did not grievously suffer. The English lost about 5,000 men.

On the Scots side, the archers of Ettrick, known in Scotland as the ‘Flowers of the Forest’, perished almost to a man. To this day the sweet, sad, wailing air known by that name is invariably the Dead March used by Scottish regiments.