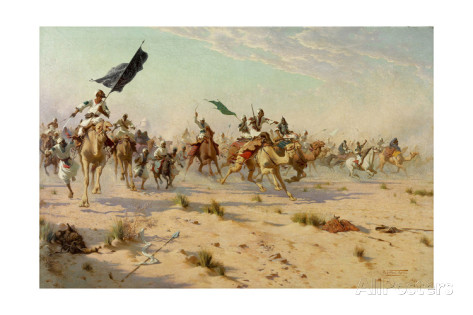

Robert Kelly’s depiction of the Khalifa’s flight was wholly imaginative, but still suggests the impact which the exotic image of dervish power had on British opinion .

Date

September 2, 1898

Location

Near Khartoum in central Sudan

Opponents

[1]British and Egyptians

[2]Sudanese Dervishes

Commander

[1]Major General Sir Herbert Kitchener

[2]Khalifa Abdullah

Approx. # Troops

[1]8,000 British, 17,000 Egyptians

[2]35,000–50,000 Sudanese Dervishes

Importance

Brings Anglo-Egyptian control of the Sudan

In the September 2, 1898, Battle of Omdurman, British, Egyptian, and Sudanese forces defeated nationalists in the Sudan, leading to the establishment of the Anglo- Egyptian Sudan. The battle also illustrated the technological advantage of European military establishments over their brave but primitively armed opponents in the wars of imperialism that preceded World War I.

Concern over the security of the Suez Canal, Britain’s lifeline to India, led the British government to send naval and land forces to Egypt in 1882. Following the Battle of Tel el Kebir on September 13, 1882, the British established their control over all Egypt. Although the khedive was still nominal ruler, the real power in the country rested with the British consul-general and high commissioner, and British imperialists soon considered the Nile Valley part of the British Empire.

From Egypt, the British were soon drawn into difficulties in the vast, poor, and hostile Sudan. Egypt had long sought to establish its control over the Upper Nile region but aroused strong opposition through actions against the slave trade and heavy taxes. In 1883 a prophet, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as-Sayyid Abd Allah, the son of a Nile boatbuilder, arose in the Sudan, calling himself the Mahdi. Soon he had thousands of warrior followers, known as Dervishes.

The Egyptian government decided to intervene to put down the uprising. Former Indian Army officer General William Hicks marched 8,500 Egyptian Army troops into the desert, only to be annihilated on November 3 at El Obeid by Sudanese forces under command of Abu Anja, one of the Mahdi’s best generals. The Mahdi’s reputation soared after this victory, and the entire Sudan was in revolt.

The Egyptians then sought assistance from the British government. The Egyptians still held the Nile and the city of Khartoum, at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, but Prime Minister William Gladstone decided that the Sudan must be evacuated. To accomplish this, he sent out Major General Charles Gordon.

Gordon’s nickname was “Chinese,” earned for his command of the Chinese Imperial Army that put down the Taiping Rebellion in the 1860s. He had once been governor of the Sudan for the Egyptians and had taken an aggressive stance against the slave trade there. Deeply religious and eccentric, Gordon was the worst possible choice for a mission involving capitulation. He completely ignored Gladstone’s original instructions and convinced the Egyptian ministry to reestablish British control in the Sudan. Gordon then proceeded up the Nile to Khartoum, where he dallied and got besieged by the Mahdists. Gladstone was furious; only after five months had passed did his government respond to public pressure and send relief forces under General Garnet Wolseley.

Wolseley’s own trip up the Nile was as slow as that of Gordon. As his relief expedition neared Khartoum and after a siege lasting 317 days, on January 26, 1885, the Dervishes swept over Gordon’s defenses, stormed the palace, and massacred the entire garrison, presenting Gordon’s severed head to the Mahdi. On June 21, 1885, the Mahdi died. His successor, Kalifa Abdullah, and his Dervish followers completed the conquest of the Sudan, with the British this time evacuating.

Not until 1896 did the British government decide to reconquer the Sudan, part of a plan to provide a defense in depth for the Suez Canal fueled by French and Italian interest in the Sudan. Under orders from London, Egyptian army commander in chief (sirdar) major general (only a colonel in the British Army) Horatio Herbert Kitchener marched forces south from Egypt. Kitchener commanded six brigades of infantry. He had only four British battalions, and most of his 25,000- man force consisted of Egyptians and Sudanese. Kitchener also had some 20 Maxim guns, artillery, and river gunboats. He had a considerable supply train of camels and horses and built a rail line as he proceeded southward.

The methodical Kitchener captured Dongola on September 21, 1896, and Abu Hamed on August 7, 1897. He then defeated Mahdist forces under Osman Dinga and Khalifa Abdullah in the Battle of the Atbara River on April 7, 1898. On September 1, 1898, Kitchener arrived outside Omdurman, across the Nile from Khartoum, to face the main Mahdist army. Among those present on the British side was 23-year-old soldier and reporter Winston Churchill.

After some preliminary skirmishing, on the morning of September 2 some 35,000–50,000 Sudanese tribesmen under Abdullah attacked the British lines. The Mahdists had perhaps 15,000 rifles, with the remainder of their men armed only with spears and swords. There was no real sense of how the troops should be deployed; riflemen were merely mixed in with the spearmen and swordsmen. The riflemen were to provide cover for the others to close with the enemy and fight hand to hand in true warrior fashion. The Mahdist riflemen also fired from the hip, standing or running, rather than from the shoulder; they considered firing from the prone position to be cowardly.

In a series of charges against the British position the Mahdists were simply annihilated, although disaster was narrowly averted that afternoon when Kitchener, who thought that the fight was over and was anxious to avoid a street battle for Omdurman, tried to place his forces between the Mahdists and the capital. As they moved, Kitchener’s infantry encountered a fresh force that had not participated in the earlier fighting. Fortunately for Kitchener, this attack came in separate waves. General Hector MacDonald’s Sudanese brigade managed to hold the Mahdists off, and the 21st Lancers charged and defeated another force that suddenly appeared on the British right flank. After the battle it was learned that the men of the Sudanese brigade were down to an average of only two rounds apiece.

During the Battle of Omdurman the British had used their magazine rifles and Maxim guns to kill perhaps 10,000 Dervishes and wound as many more, with 5,000 taken prisoner. The cost to the British side was 48 dead and 434 wounded. Kitchener, surveying the battlefield from horseback, is said to have announced (in considerable understatement) that the enemy had been given “a good dusting.” The battle led Hilaire Belloc to have the character Blood proclaim in The Modern Traveller:

“Whatever happens we have got The Maxim Gun, and they have not.”

The Battle of Omdurman also gave Britain control of the Sudan for all practical purposes, and made Kitchener a British national hero.

References Barthorp, Michael. War on the Nile: Britain, Egypt, and the Sudan, 1882–1898. Poole, UK: Blandford, 1984. Harrington, Peter, and Frederick A. Sharf. Omdurman, 1898: The Eye-Witnesses Speak. London: Greenhill Books, 1898. Spiers, Edward M., ed. Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised. London: Frank Cass, 1998. Vandervort, Bruce. Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830–1914. London: UCL Press, 1998.