Charles d’Anjou, who had conquered Sicily in 1266, allied himself with Prince Edward of England, who had arrived in Tunis in 1270. When Charles d’Anjou called off the attack on Tunis, Edward went on to Acre, the last Crusader outpost in Syria, in an attempt to restore the “Kingdom of Jerusalem”. His time spent there (1271–1272) is called the Ninth Crusade. This crusade is considered to be the last major mediæval Crusade to the Holy Land. The Ninth Crusade failed largely because the crusading spirit was nearly extinct in Europe, and because of the growing power of the mamluks in Egypt. It also foreshadowed the imminent collapse of the last remaining Crusader strongholds along the Mediterranean coast.

Edward of England and Charles d’Anjou of Sicily decided that they would take their forces onward to Acre, capital of the remnant of the “Kingdom of Jerusalem” and the final objective of Baibars’ military campaign. The armies of Edward and Charles arrived in Acre in 1271, just as the able and cruel Baibars was besieging the city of Tripoli, which, as the last remaining Christian area of the County of Tripoli, had tens of thousands of Christian refugees. From their bases in Cyprus and Acre, Edward and Charles managed to attack Baibars’ interior lines and break the siege of Tripoli. This was the first Crusader victory in many years.

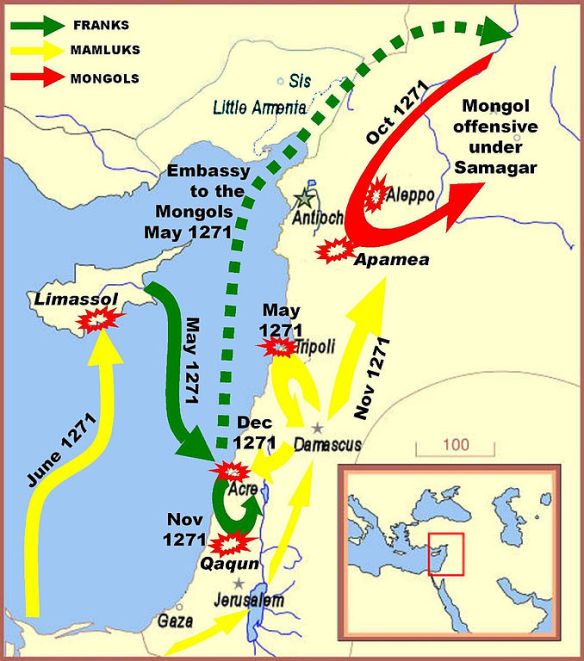

As soon as Edward of England arrived in Acre, he tried to ally himself with the Mongols, sending an embassy to the Mongol ruler of Persia, Abaqa Khan (1234–1282), an enemy of the Muslims. The Mongols had sacked Muslim Baghdad in 1258, and Edward believed that they would ally themselves with the Christians. The embassy to the Mongols was led by Reginald Rossel, Godefroy de Waus, and John of Parker. In an answer dated 4 September 1271, Abaqa Khan agreed to co-operation and asked at what date the concerted attack on the mamluks should take place.

The arrival of the forces of King Hugues III of Cyprus, the nominal king of Jerusalem, in Acre emboldened Edward, who raided the “Saracen” town of Qaqun, near Nablus. At the end of October 1271, a small force of Mongols arrived in Syria and ravaged the land from Aleppo southward. However, Abaqa Khan, occupied by other conflicts in Turkestan, could only send 10,000 Mongol horsemen under General Samagar from the occupation army in Seljuk Turkish Anatolia, with some auxiliary Seljuk troops. Despite the relatively small force, their arrival triggered an exodus of Muslim populations (who remembered the previous campaigns of Kitbuqa) as far south as Cairo. The fierce and ruthless Mongols were deeply feared. But the Mongols did not stay, and when the mamluk leader Baibars mounted a counter-offensive on the Mongols from Egypt on 12 November, the Mongols had already retreated beyond the Euphrates into Persia.

Baibars suspected that there would be a combined land-sea attack on Egypt by the Franj. Feeling his position threatened, he endeavoured to head off such a manoeuvre by building a large fleet. Having finished construction of the fleet, rather than attack the Crusader army directly, Baibars attempted to land on Cyprus in 1271, hoping to draw King Hugues III of Cyprus (the nominal King of Jerusalem) and his fleet out of Acre, with the objective of conquering the island and leaving Edward and the Crusader army isolated in the “Holy Land”. However, in the ensuing naval campaign, the Egyptian fleet was destroyed and Baibars’ armies were routed and forced back.

Following this temporary victory over the “Saracens”, Edward of England realized that it was necessary to end the internal rivalry within the Crusader state. He mediated between Hugues and his unenthusiastic knights from the Ibeline family of Cyprus. After the mediation, Prince Edward of England began negotiating an eleven- year truce with Sultan Baibars of Egypt, although, according to some sources, this negotiation almost ended when Baibars attempted to assassinate Edward by sending men pretending to seek baptism as Christians. Edward and his knights personally killed the assassins and at once began preparations for a direct attack on Jerusalem. However, when news arrived that Edward’s father, Henry III, had died in England, a peace treaty was signed with Sultan Baibars, allowing Edward to return home to be crowned King of England in 1272. The Ninth Crusade thus ended without any of its goals, above all the capture of Jerusalem, being realized.

After the Ninth Crusade

After the Ninth Crusade (1271–1272), the mamluks, who now ruled in Egypt, repeatedly tried to take Acre from the “Franks”. Edward of England had been accompanied on his crusade by Theobaldo Cardinal Visconti, who, in 1271, became Pope Gregory X. Gregory called for a new crusade at the Council of Lyons in 1274, but nothing came of this. Europe’s crusading spirit had died. New fissures arose within the Christian states in the “East” when Charles d’Anjou of Sicily took advantage of a dispute between Hugues III of Cyprus (the “King of Jerusalem”), the Knights Templar, and Venice in order to bring the remaining Crusader state under his control. Having bought Princess Mary of Antioch’s claims to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Charles attacked Hugues III, causing a civil war within the rump kingdom. In 1277, Hugo of San Severino captured Acre for Charles. In that year, Sultan Baibars of Egypt died, as did the Caliph of Tunis, Muhammad al-Mustansir.

Although the civil war within the Crusader ranks had weakened them badly, it also gave the opportunity for a single commander to take control of the crusade: Charles d’Anjou, King of Sicily. However, this hope, too, was dashed when Venice again suggested that a crusade be called, not against the “Saracens”, but against the Greeks of Constantinople, where, in 1261, Michaelis VIII Palalelogos (1223–1282) had toppled the “Latin Kingdom of Constantinople”, re-established the Byzantine Greek Empire, and driven out the Venetians as well. Pope Gregory X would not have supported an attack by Christians on Christians, but, in 1281, his successor, Pope Martin IV, did. This led in 1282 to the “War of the Sicilian Vespers” (1282–1302). The war began as a popular Sicilian uprising against King Charles d’Anjou, who had conquered Sicily in 1266, and was instigated by Emperor Michaelis VIII of Byzantium. Charles d’Anjou was driven from Sicily, and the French and Norman population of Sicily was massacred.

The Ninth Crusade was the last Crusader expedition launched either against the Byzantines in Europe or the Muslims in the Holy Land. During the remaining nine years (1282–1291), the mamluks demanded ever increasing tribute from the “Franks”, and also persecuted the Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem, in contravention of their truce with Edward of England. In 1289, the mamluk sultan Qalawun al-Alfi of Egypt gathered a large army and attacked the remnants of the Christian County of Tripoli, laying siege to its capital of Tripoli, and finally taking it after a bloody assault. Their attack on Tripoli was terrible for the mamluks themselves, however, as the desperate and frenzied Christian resistance to the siege reached fanatical proportions. Qalawun lost his eldest and ablest son in the Tripoli campaign. He waited another two years to gather his strength. Qalawun died in 1290, but, in 1291, the mamluks, under his son Khalil (al-Malik al-Ashraf Salah ad-Din Khalil ibn Qalawun, 1262–1293), took Acre from the Crusaders.

The fall of Acre was tragic and bloody. Following the fall of Tripoli to the mamluks in 1289, King Henry of Cyprus desperately sent his seneschal Jean de Grailly to Europe to warn the European monarchs about the critical situation in the “Levant”. In Rome, Jean de Grailly met Pope Nicholas IV (Girolamo Masci, 1227–1292), who promptly wrote to the European princes urging them to do some- thing about the “Holy Land”. Most of them, however, were too preoccupied by the “War of the Sicilian Vespers” to organize a crusade, and King Edward of England was entangled in his own troubles at home. Only a small army of Italian peasants and unemployed Italians from Tuscany and Lombardy could be raised. They were transported in twenty Venetian galleys, led by Nicolò Tiepolo, son of the Doge of Venice, who was assisted by Jean de Grailly. As they sailed eastward, the fleet was joined by five Spanish galleys from King James of Aragon, who wished to help despite his conflict with the pope and Venice.

The fall of Acre and the final fall of the “Kingdom of Jerusalem” was preceded by a tragic massacre of Muslims by Christians. In August 1290, the inexperienced and poorly controlled peasants from Italy killed Muslim merchants and peasants in and around Acre without the permission of Acre’s Christian rulers. These killings gave the mamluk Sultan Qalawun a pretext to attack Acre. Although a ten-year truce had been signed between the mamluks and the Crusaders in 1289, Qalawun deemed the truce null and void following the killings. Qalawun first asked the Crusaders for the men guilty of the massacre to be handed over to him so that he could execute them. Guillaume de Beaujeu, the Grand Master of the Knights Templar, proposed handing over the Christian criminals from Acre’s jails, but the Council of Acre finally refused to hand over anybody to Qalawun, and instead tried to argue that the killed Muslims had died because of their own fault. At one point during the siege, Guillaume de Beaujeu dropped his sword and walked away from the walls. When his Templar knights remonstrated, Beaujeu reportedly replied: “Je ne m’enfuis pas; je suis mort. Voici le coup.” (I am not running away; I am dead. Here is the blow.) He raised his arm to show the mortal wound he had received (Barber, 2001, Crawford, 2003).

After the Council of Acre refused to hand over the culprits for the massacre of the “Saracens”, Sultan Sultan Qalawun ordered a general mobilization of the mamluk armies of Egypt. Though he died in November 1290, he was succeeded by his son Khalil, who soon led the forces attacking Acre. The island of Cyprus at that time was the base of operations for the three major Crusader orders: the Knights Templar, the Teutonic Knights, and the Knights Hospitaller. These orders sent their knights to Acre, which was well fortified, and now had these three groups of defenders. The population of Acre at the time was some 40,000 souls, its troops numbering around 15,000, and an additional 2,000 troops arrived on 6 May 1291, with King Henry II from Cyprus. There are no reliable figures for the mamluk army, though it was certainly larger than the Crusader troops, with most of the force being volunteer siege workers. The siege lasted six weeks, beginning on 6 April 1291 and ending with the fall of the city on 18 May. According to a nineteenth-century painting by the French painter Dominique-Louis Papéty (1815–1849), the Grand maître hospitalier, Guillaume de Villiers, and the maréchal des Hospitaliers, Mathieu de Clermont, were among the leaders and last defenders of Acre. This is by no means certain, however, as the Knights Templar held out in their fortified headquarters in Acre until 28 May.

After the mamluks took Acre, they utterly destroyed it, so as to prevent the “Franks” from ever taking it again and re-establishing their kingdom. Within months, the remaining Crusader-held cities in the “Holy Land” fell easily, including Sidon (14 July 1291), Haifa (30 July), Beirut (31 July), Tartus (3 August), and Atlit (14 August). Only the small Mediterranean island of Arados or Arwad, off the Syrian coast, held out until 1302 or 1303. For the European Christians, this was the tragic end of the “Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem”, which had been based on psychohistorical and psychogeographical fantasies from its very outset. The Baltic Crusades, however, continued well into the fifteenth and even the sixteenth century. Paying no heed to Roger Bacon, the thirteenth-century Doctor Mirabilis, the Franciscan monk who wrote that religion can only be acquired by preaching, not imposed by war, the European Christians continued to try to impose their religion on the “heathen Saracens” of the Baltic region by the sword. Those who cannot mourn their losses, those who are unsure of their own faith, tragically try to force others to believe as they do.