4th June 1919 – British submarine ‘L.55’ (1918, 960t, 6-21in tt, 2-4in). With the British Baltic Squadron blockading the Bolshevik naval base of Kronstadt on Kotlin Island laying off Petrograd, warships on both sides were lost. On the 4th (some accounts say the 9th) ‘L-55’ was in action with Russian patrols and sunk by the gunfire of destroyers ‘Azard’ and ‘Gavriil’. She is later raised and commissioned into the Soviet Navy as ‘L-55’

Here, at the outset of the First World War, the Germans compelled the Russian Navy to abandon Libau and withdraw into the Gulf of Finland. This posed two problems: how to prevent the High Seas Fleet maintaining its efficiency by exercising undisturbed in the southern Baltic; and how to disrupt Germany’s ore imports from neutral Sweden’s mines at Luleå in the Gulf of Bothnia. On learning that Russia’s submarines were immobilised for lack of spares, the Admiralty ordered E1, Lieutenant-Commander Noel Laurence, E9, Lieutenant-Commander Max Horton, and E11, Lieutenant-Commander Martin Nasmith, to penetrate the Kattegat in October 1914, and attempt the passage of the Sound, scene of one of Nelson’s trio of immortal victories. Nasmith was unlucky; delayed by an engine defect, he was detected by German patrols in these shallow waters and obliged to turn back; but Horton and Laurence completed the 1,200-mile journey to Reval (now called Tallinn). And from there, in the short time that remained before ice froze them in for the winter, E1 and E9 proved their worth; by attacking German transports they compelled the enemy to abandon an attempt to capture Petrograd (long famed as St Petersburg soon to be re-named Leningrad) by a series of amphibious landings along the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland.

This success decided the Admiralty to reinforce their Baltic flotilla with four more boats. In the spring of 1915, E8, Lieutenant-Commander F. H. H. Goodhart, E18, Lieutenant-Commander R. C. Halahan, and E19, Lieutenant-Commander F.A.N. Cromie, passed safely through the Sound despite increased vigilance by German patrols; but Lieutenant-Commander Geoffrey Layton had the misfortune to run E13 aground on the Danish island of Saltholm, where she was shelled by enemy torpedoboats. Although the British flotilla was under the operational control of the Russian C-in-C, Admiral Kanin, and his Commodore Submarines, Podgoursky, its own senior officer, Horton, was chiefly responsible for seeing that it did not lapse into the inactivity that characterised the Russians. And right well he did this, despite the special difficulties that faced submarines in the Baltic: its low salinity made depth-keeping difficult, and the short summer nights allowed little time for charging batteries on the surface under the cover of darkness. E9 had an early success off Libau in May: attacking a heavily escorted German troop convoy, Horton sank one of the transports, which was enough to send the rest scurrying back to harbour. In the next month he torpedoed another transport and in July he crippled the cruiser flagship, SMS Prinz Adalbert. Submarine E1 was as active but out of luck until August, when Laurence disabled the powerful battlecruiser Moltke while she was covering an operation against the Gulf of Riga. Finally, E8 sent the repaired Prinz Adalbert to the bottom before the British flotilla was diverted to interrupting the iron ore traffic from Luleå, a task involving the additional hazard of complying with International Law—the need to give the crew of each intercepted freighter time to take to the boats before sinking her. The many minefields with which the Baltic was sown were another danger, to which E18 succumbed with all hands. And E19 nearly met disaster in an anti-submarine net laid across Lübeck Bay before Cromie completed a successful torpedo attack on the light cruiser Undine—by which time the Germans had such a healthy respect for the British flotilla that they called the Baltic ‘Horton’s Sea’.

Horton and Laurence were called home for service in new submarines in January 1916, leaving the mantle of senior officer to Cromie. No better man could have been chosen for the exceptionally difficult task which lay ahead. It was not his fault that his flotilla achieved little this summer: Kanin and Podgoursky were obsessed with the possibility of a further enemy attack on the Gulf of Riga, and restricted the British boats to defensive patrols. But the prospects for 1917 seemed brighter when these officers were relieved by the more intelligent Admiral Nepenin and the energetic Commodore Vederevsky, and the Admiralty sent as reinforcements, by way of Archangel, four ‘C’ class boats that were small enough to proceed thence by canal and lake to Petrograd, thus avoiding the now too hazardous passage of the Sound. With as many as eight submarines, Cromie expected no difficulty in dominating the greater part of the Baltic. But, in the event, he was faced with a more insidious enemy. The February Revolution broke whilst he was visiting the Russian capital, where he experienced the anger of the mob when it broke into the Astoria Hotel and saw, too, that the mutinous garrison was supported by sailors from Kronstadt. Hurrying back to Reval, the ominous calm onboard the Russian depot-ship was broken soon after his return by the arrival of two members of the Duma to enlist support for the Provisional Government. The Dvina’s crew responded to this appeal by breaking ship and joining the workers ashore in demonstrations against the Imperial régime. Fortunately, there was little bloodshed, nothing compared with the mutiny at Kronstadt, where Admiral Nepenin was among 300 officers brutally butchered. And though Cromie could not prevent the Dvina’s company electing a soviet, which replaced the Russian ensign with the red flag and changed her name to Pamyat Azova, he did persuade them to allow Captain Nikitin to retain his command, and to spare the lives of their more unpopular officers.

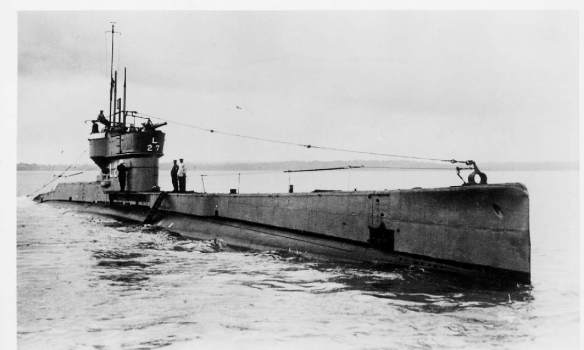

Command of the Baltic Fleet now passed, first to Admiral Maximov who sought to placate his men by wearing a red tie and rosettes, then to Vederevsky, before both were succeeded by the much abler Admiral Razvosov. But even he was powerless to do much without the agreement of the Tsentrabalt; and although this Central Soviet agreed to continue the war, very few of the Russian ships were in a fit condition to fight, after so many of their officers had been murdered. Nor were the British submarines allowed to take the offensive; they had to be conserved against a German advance on Petrograd. The Pamyat Azova was moved to Hango, from where the four class boats patrolled the entrance to the Gulf of Finland, and the class moved into the Gulf of Riga. Here, soon after the Latvian capital fell in September 1917, enemy minesweeping and bombing from the air made clear that the Germans were about to assault the islands of Ösel, Dagö and Moon, whose guns dominated the entrance. The Russian Navy’s attempts to impede this activity proved futile: the crews of two destroyers abandoned ship precipitately as soon as one ran aground: the battleship Kretchet was ignominiously mined into Moon Sound whilst wearing Razvosov’s flag. And it was not until after the Germans had completed an unopposed landing on Ösel on 12 October, where the forts surrendered without a struggle, that Cromie was allowed to send his submarines against the enemy. Lieutenant D. C. Sealy in C27 sank a torpedoboat and crippled a transport as soon as the evening of the 15th; but C26, Lieutenant B. N. Downie, and C32, Lieutenant C. P. Satow, were unable to reach the area until after the German fleet had anchored off Moon island. Satow managed to penetrate this anchorage and torpedo a transport, but Downie was not so fortunate. When he chanced to run his boat aground, his struggles to free her brought her to the surface, with the consequence that he and Satow were hunted almost to exhaustion before they managed to escape to Pernu.

The October Revolution, and the opening of armistice talks at Brest-Litovsk, rendered the British flotilla’s already unenviable position exceptionally precarious. There was no possibility of escape from the Baltic; even if the Sound had not been so closely patrolled as to make this impracticable, the German delegates at Brest-Litovsk required the Russians to keep Allied ships in port. There was also a strong possibility that the Tsentrabalt would turn against the British officers and men, after agreeing to surrender their own fleet. However, after preparing a plan to use his submarines to torpedo the Russian ships should they try to leave harbour, Cromie talked the Bolsheviks out of such treachery, and persuaded them to guarantee the safety of their erstwhile allies. The Admiralty then ordered the British crews to withdraw by way of Murmansk, leaving their submarines at Helsinki in the hands of small care and maintenance parties.

Those that remained included Cromie, who became naval attaché in Petrograd, and Downie who stayed aboard the Pamyat Azova to ensure that the British flotilla did not fall into enemy hands. This was in January 1918. But the arrival of German troops at the end of March, to help the Finns in their fight against the Reds, left Downie with no alternative: one by one he took his submarines to sea, and scuttled them. Then he and his little band of men went home by way of Murmansk. Only Cromie remained: ‘the young officer who had arrived, thinking of little beside his crew, his equipment and his operations, had become the de facto ambassador of Great Britain in Petrograd’, wrote Sir Samuel Hoare. ‘There for six months he maintained the British front in the face of difficulties and dangers as formidable as any that he had met in the Baltic’ His task was to prevent the Russian fleet falling into German hands, but inevitably he became enmeshed in intrigues with the Whites and more and more suspect by the Reds, so that by August he had outlived his usefulness. The British representative in Moscow, Bruce Lockhart, urged him to leave, but Cromie was reluctant to go and delayed too long. On the day that Lockhart was arrested, the Cheka burst into the Embassy. Cromie appeared at the head of the staircase prepared to defy the intruders, shots were fired, and a very gallant officer fell, mortally wounded.

(To this unhappy end to the story of the British flotilla in the Baltic, a postscript must be added. Nearly 40 years later HM Submarine Amphion visited Helsinki to mark the centenary of the bombardment of Sveaborg by Dundas’s fleet, in which one of her namesakes was the only British ship to sustain a casualty. And to her the Finnish Navy presented the builder’s name-plate, of polished brass, mounted on teak, from one of the scuttled ‘E’ class boats, whose salvage from the approaches to the port had just been completed.)

EASTERN FRONT and BALTIC SEA, 1914-18

also Russian Bolshevik Waters 1919