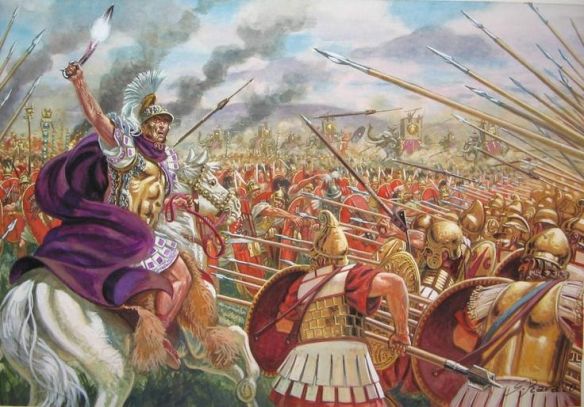

Rome’s war against that infamous Hellenistic condottiere king Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 to 275 that finally brought Rome fully into the purview of Hellenistic international relations. Pyrrhus at the battle of Ausculum.

Army of Pyrrhus by Johnny Shumate

The Greeks of south Italy and the Adriatic now looked to Rome as their protector rather than to the Spartan colony of Tarentum. The Tarentines believed that Rome had usurped the position that was rightfully theirs and, in 281, they attacked a small Roman fleet en route to the Adriatic to suppress piracy. Roman ambassadors sent to Tarentum to demand redress arrived during a festival when the Tarentines were drunk. A large crowd gathered and mocked the Romans. One drunk flung his own feces at the Roman ambassador. The Roman ambassador departed but left in the air the ominous remark, “You will wash my garment clean with your blood.”

When the Tarentines sobered up, they realized that they had made a bad mistake, but they then made a worse one. They appealed to Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus, to protect them. Pyrrhus knew little of the Romans, but he was an experienced general who was confident in his own abilities and in his phalanx, cavalry, and elephants. He came west not to champion the Tarentines, but to fulfill an old ambition, to unite the Greeks of Italy and Sicily in a league with himself as hegemon (as Philip and Alexander had been hegemons of the Hellenic League). Pyrrhus had been told 300,000 Italic natives stood ready to serve him. To prevent this fiction from becoming reality, the Romans garrisoned south Italy and sent a consular army to winter in Samnium.

In the beginning of the campaigning season of 280 B. C. the Roman consul forced an engagement on Pyrrhus at Heraclea. On the eve of the battle Pyrrhus observed the Romans pitching camp. When he saw the fortified camp they built, he exclaimed, “These are not barbarians.” In the morning he stationed his elephants on his flanks to frighten off the Roman cavalry and used his phalanx to break the legions. The Romans lost 7,000 men; Pyrrhus lost 4,000. The master tactician, upon being congratulated for his victory, said, “Yes, one more like it and we are done.” Pyrrhus marched on Rome, but he found few allies, and forty miles from Rome he turned back. He offered the Romans what he thought were generous terms: the Romans would guarantee Greek autonomy, and they would withdraw from the territory of the Samnites, Lucanians, and Bruttians. The Senate rejected the terms.

In the spring of 279 a double consular army met Pyrrhus at Asculum near the Aufidus River. The battlefield was rugged and unsuited to a phalanx, but Pyrrhus had created a flexible phalanx by putting maniples of Samnites and Lucanians between units of his phalanx. The two armies fought all day without a decision, but early the next morning the king seized favorable ground and broke the legions. The Romans retreated to their camp and defended it successfully. One consul and 6,000 Romans had been killed. Pyrrhus lost 3,500 men and was himself wounded. He had won a battle, but his next step was not clear.

At this point he was invited by Sicilian envoys to come put Sicily in order. Sicily was in turmoil because of the death of the Syracusan tyrant Agathocles -Pyrrhus was the son-in-law of Agathocles-and because the Carthaginians had launched an invasion. Pyrrhus offered the Romans a truce with but one demand-that the Romans recognize the territorial integrity of Tarentum. The Senate might have agreed, had a Carthaginian admiral (with his whole fleet of 120 ships) not appeared and offered to subsidize the war against Pyrrhus, to use his fleet to blockade Pyrrhus in Tarentum, and to transport Roman troops to Sicily, if they wished, to carry on the war against Pyrrhus there. The Romans accepted the Carthaginian treaty, and the two consuls with their armies advanced on Tarentum. Pyrrhus sailed for Sicily and left the Romans with a free hand to regain control of southern Italy.

After some initial successes in Sicily Pyrrhus’s schemes collapsed, and in the spring of 275 he gave up and returned to Tarentum with a much-reduced force. The two Roman consuls were operating separately against Pyrrhus’s former allies-none of them would help him now-and Pyrrhus tried to defeat one consul before the other could come to his aid. At Beneventum he fought his third grim battle against the Romans; the day ended without victory for either side, but that night the other consul reached the battlefield, and Pyrrhus withdrew. Pyrrhus left a garrison in Tarentum and returned to Epirus with but a third of the forces he had brought to Italy. The Romans won this war without ever having defeated Pyrrhus in battle.

The Roman victory brought them to the attention of the eastern courts. The court poet of Ptolemy, king of Egypt, identified the Romans with the Trojans who escaped from the sack of Troy under the leadership of Aeneas, and Ptolemy made a pact of friendship with them. The victory also gave the Romans a free hand in south Italy. They subjugated the native peoples, confiscated territory, and settled colonies to further divide these people from each other and from themselves. In 272-Pyrrhus was killed in a skirmish in Argos: an old woman threw a roof tile which stunned him, and a Gallic mercenary cut off his head-the Romans laid siege to Tarentum. The consul in command made a private deal with the Epirote garrison by which they handed over the citadel to him and were allowed to leave unharmed. The Romans treated the city with decency, accepted it as a naval ally, and permanently garrisoned the citadel with a legion, both to watch Tarentum and to protect southern Italy. The Romans were now masters of the greatest resource of military citizen manpower in the western world: a quarter of a million citizen-soldiers.

Pyrrhus at Heraclea

Pyrrhus invaded Italy after “invitation” made by Tarentines, who called for help against Romans. Pyrrhus in preparation for invasion asked Ptolemy Ceraunus for help, which Ptolemy found this as good way how to get rid of Pyrrhus for time being, and to have open options in Macedonia, against Antigonus Gonatas. He sent 3000 cavalry and 20 elephants to Pyrrhus. Together Pyrrhus managed to muster 20000 heavy infantry (majority Epirote Pikemen, but also Macedonian and also a lot of Mercenaries from Greek states), 3000 horse, 2000 archers and 500 slingers. Transporting this force over sea to Italy was feat of its own, as so far, nobody was able to transport elephants over open sea. yet, Pyrrhus fleet even got into a storm, which scattered whole fleet, so Pyrrhus landed with just 2000 men and 2 elephants, all 20 elephants survived transport which was an unprecedented accomplishment of their handlers, he marched to Tarrentum with this small force, and practically did nothing, until remaining of fleet landed. At that point he set up a garrison, and started to forcibly recruit Tarentines into his army. Some tried to escape, but garrison managed to catch a lot of them. He was afraid of their loyalty, therefore he mixed them into his Epirote Pikemen formations.

Romans, after they discovered Pyrrhus landed with force, started to prepare for war. They sent garrison to Rhegium, another to Locri, while they kept strong force in Rome as well. One army under consul Aemilius was sent to territory of Samnites another army under Tiberius Coruscanius was sent to north to block Etruscans, new consul, Publius Valerius Laevinus, was given command of largest army, 4 legions, and marched directly to Tarrentum. His goal was to force Pyrrhus into battle, so he would be not able to rise more troops from local allies. Roman plan succeeded, Pyrrhus learned that Roman army is threatening Greek city of Heraclea, before he could join the force with Italian allies, numbers for both sides are not precisely recorded anyway they can be estimated from known sources, Laevinus had 4 legions with him, plus allies, which should represent strength of 40000 men and 2400 cavalry.

Pyrrhus embarked with 25500 infantry, 3000 cavalry and 20 elephants, anyway he had to leave some as garrison in Tarrentum, and also he lost some men in the storm. Anyway he had about 20000 Tarrentine Levies and another 2000 Tarentine cavalry, anyway some cavalry and infantry had deserted.

Weaponry of Tarentines is still a matter of speculation, prior to Pyrrhus arrival they were fighting in standard hoplite phalanx, anyway it is mentioned that Pyrrhus imposed a rigorous training and incorporated them in small numbers into his Epirote Pike units. Therefore it is likely but not certain that his Tarentine levy was armed as pikemen as well, otherwise they would be not able to be added to Epirote units. (anyway later at Asculum, Frontinus report them standing separate in the center)

Pyrrhus initial plan was to delay battle as far as he could, while preventing Romans to raid the country, so his Italian allies could come to him. Romans on the contrary, wanted to bring the battle as soon as possible.

The most likely site of the battle is a river plain, about 6km from Heraclea. Pyrrhus learned Romans have a camp on the other side of the river, and he came to observe the enemy. Romans immediately called to arms, and their infantry force marched forward through the fords, while cavalry force at the same time used different crossings. Epirote skirmish formation threatened by infantry and cavalry became withdrawing. Pyrrhus ordered his infantry to form a battle line, while keeping all his elephants and some cavalry in reserve, while infantry was forming up, Pyrrhus himself led his cavalry, 3000 horsemen in attempt to catch Romans scattered as they moved through the crossings. Anyway part of Roman Cavalry force already crossed, and were formed into formation. Pyrrhus formed up his cavalry and attacked, he fought in front line, and his ornamented armor was clearly visible to his men but also to enemy. At some point of this combat, some Roman cavalrymen, who wanted to prove himself tried to engage Pyrrhus in single combat. Kings bodyguards managed to kill his horse, anyway Roman managed to get through and killed Pyrrhus horse with his spear, with Pyrrhus falling off the horse. He was saved in last moment by his bodyguards, while Roman cavalrymen was killed, anyway he was alarmed by close call, he decided to give his cloak and armor to his best and bravest companion – Megacles. Pyrrhus dressed in simple cloak and armor to not be so easily distinguishable in battle. Due to Roman infantry getting closer in support of their cavalry, Pyrrhus called off his cavalry and retreated to his positions. At that point he ordered his Infantry to march forward, and he again personally joined the combat. Initial combat was started by light infantry throwing their javelins and stoned at each other. Pyrrhus ordered his Phalanx to march forward hoping to trap the Roman Infantry with their back against river. When heavy infantry came into range, they charged against Epirotes, throwing their Pila. Some of them were deflected by pikes of the rear ranks, anyway some caused casualties, yet these were immediately replaced by men in rear ranks, per Plutarch, battle was for long time in balance and neither side gained upper hands, which means Romans found the way how to cause casualties to Epirotes, which calls the claims of some Greek historians of Phalanx being unstoppable into question. Possibly, supposed invincibility of phalanx was overstated to magnify the later Roman victories against Macedonians, as ancients believed, that “greater challenge provides greater glory to the victor”.

At some point Pyrrhus decision to dress Megacles in his armor proved to be almost a disaster, as he was slain by Romans, which caused huge morale drop in Epirote ranks who thought their king is dead. Pyrrhus was forced to ride along the battle line to prove he is still alive.

As a bad luck, battle was decided by Laevinus, when his detachment of cavalry who managed to get to the Epirote rear, forced Pyrrhus to use his elephants. Sight of these animals, Romans seen for the first time caused the panic in Roman cavalry who routed and left the field. Pyrrhus used his Tarentine cavalry to charge into Roman infantry while it was disordered and he completed the rout. With one wing of Roman cavalry routed, flank of Roman infantry position was exposed. Pyrrhus ordered his elephants to attack that flank. Roman infantry started to give ground, anyway during withdrawal some Roman soldier managed to wound one of elephants that started to wreak havoc in own ranks, due to confusion Pyrrhus rather called of the pursuit and let the Romans withdraw through the river.

by his own words:

“never to press relentlessly on the heels of an enemy in flight, not merely in order to prevent enemy from resisting too furiously in consequence of necessity, but also to make him more inclined to withdraw another time, knowing the victor would not strive to destroy them in flight”

With battle over, Plutarch reported 7000 dead Romans and 4000 dead Epirotes. Dionysius claimed 15000 dead Romans and 13000 Epirotes, yet, most historians consider Plutarch’s numbers to be more accurate. Pyrrhus loses were particularly heavy amongst Epirote commanders. Pyrrhus himself commented this:

“If we ever conquer again in like fashion, it will be our ruin”