At the Hitler Line, a single Panzerturm had systematically knocked out thirteen North Irish Horse tanks in minutes.

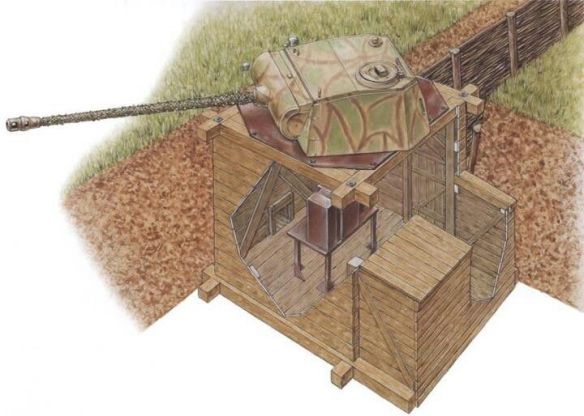

Fighting defensively, and sited to take best advantage of the terrain, a Pantherturm had several advantages over tanks, artillery or standard bunkers.

- It’s low silhouette made it easy to conceal and, once located, difficult to target from ground and air.

- It had more room for ammunition storage and a crew room, with facilities for cooking and sleeping, This gave the Pantherturm greater endurance than tanks which had to be refuelled and rearmed several times a day.

- With its most vulnerable elements buried underground, a Pantherturm was harder to knock out with artillery or air strikes. Once the Germans began using specialised turrets, with reinforced roofs and no cupola, even direct hits were often ineffective.

- A Pantherturm was quicker and cheaper to build than a tank and only a little more difficult to transport to the front. They could be deployed in greater numbers than tanks, which could be held in reserve for counter attacks.

- The turret enabled the the Pantherturm to use its main armament over 360°, whereas conventional bunkers were normally oriented in one direction, with a limited field of fire. That armament, the 7.5cm L/70, was one of the best tank and anti-tank weapons of the War, with better performance than the first generation of 8.8cm flak guns and their derivatives. It was far more powerful than the armament usually found in the recycled turrets from obsolete or knocked out tanks which were used in other defences.

- The prefabricated Pantherturm could be installed quickly using only semiskilled labour. Their were often better built than locally fabricated defenses and, because they were standardised, the men who manned them could be pretrained before deployment, rather than learning a unique installation “on the job”.

- Although the Pantherturm lacked the versatility of tanks and mobile artillery, they were a cost, and manpower, effective solution to a particular tactical situation. A cluster of mutually supporting Pantherturm could dominate a valley or mountain pass. They were a daunting prospect to any Allied commander tasked with attacking them.

The Gothic Line took advantage of a major Italian topographic feature. From the toe of Italy, the Apennines run like a hard spine virtually up the peninsula’s centre to the upper Tiber River. Here, abruptly, the mountains turn northwest to cut across the peninsula and join the Maritime Alps on the French border. This sharp dogleg separates central Italy from the great basin of the Po River Valley and Lombardy Plains to the north. Cutting as they do across the breadth of Italy, the mountains present a natural strategic barrier. Only on the east coast do they fall away sufficiently to allow relatively straightforward north-south passage. Even here, though, a series of spurs juts out from the mountains in the form of ridges, like the fingers of splayed hands, to touch the Adriatic Sea.

The Apennines’ northwest dogleg is about 140 miles long and varies in depth from 50 to 60 miles. In 1944, only eleven, mostly poor roads transected the mountains from south to north. Carved out of the flanks of narrow valleys and crossing steep passes, these roads were subject to heavy winter snowfall and torrential year-round rains. To the west, the passes soared to heights of 4,300 feet. In the centre, where Highway 65 linked Florence and Bologna, the highest pass was only 2,900 feet and the distance through the mountains just 50 miles. It was, however, a rugged route with many easily defended choke points.

Even before the Allies invaded Italy, the Germans had been so impressed by the defensive potential of the northern Apennines that OKW believed no more than a delaying operation should be fought to their south. Hitler had advised Mussolini of this on July 19, 1943, while the Sicilian campaign was still being fought. On August 18, OKW had issued an operations order to the effect that, should Italy surrender, “Southern and Central Italy will be evacuated, and only Upper Italy, beginning at the present boundary line of Army Group B (line Pisa–Arezzo–Ancona) will be held.”

Initially, Kesselring had only been responsible for operations in the southern part of Italy, while Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel commanded Army Group ‘B’ in the north. Increasingly pessimistic after the destruction of his Afrika Korps and the loss of Sicily, the Desert Fox became the leading proponent for maintaining the August 18 plan. Within weeks of the Allied landings in Italy, however, Kesselring began advocating a different strategy—development of a series of fortified lines in southern Italy to check the Allied advance south of Rome. Ultimately, Kesselring prevailed and the Allies were forced to pay a high price in both casualties and long delays in order to fight their way through one defensive line after another.

The strategy exacted a price from the Germans as well, for they had to divide their efforts to construct defensive lines. Such dispersion of resources meant that by early August 1944 the Gothic Line appeared far more formidable on paper than it was in reality. Kesselring had realized this deficiency the previous January when Allied landings at Anzio threatened the rear of the Gustav and Hitler lines. Near the month’s end, Kesselring had issued an order, intercepted by Ultra, to “develop the Apennine position with the greatest energy,” with special attention to the eastern flank at Pesaro because of the lack of inherent physical features favourable to the defence.

Despite Kesselring’s desire for haste, construction progressed slowly throughout the winter and early spring of 1944. In April and May, Ultra code-breakers provided General Harold Alexander, Deputy Supreme Commander, Mediterranean with the contents of detailed engineering reports on Gothic Line progress. The reports revealed that the line’s readiness state varied greatly from one sector to another, with the eastern flank less developed than the western flank and the interior mountains having received the least attention of all.

On June 2, with the fall of Rome imminent, OKW took renewed interest in the work and issued a comprehensive order that set out point-by-point tasks and the means that would be provided to ensure their completion. Sectors that provided the most open ground for tank manoeuvre, such as the eastern flank on the Adriatic coast, were to be protected by the deadly Panzerturms that had destroyed so many Allied tanks during the May 24 breaching attack on the Hitler Line. Each Panzerturm was a fabricated steel-and-concrete shelter dug into the ground and mounted with a turret from a disabled Panther Mark V tank. The turret could rotate through a 360-degree field of fire and its powerful 75-millimetre gun had a maximum range of 1,200 yards. These well-camouflaged gun positions were difficult to detect by aerial reconnaissance. They were also virtually immune to Allied tank or artillery fire. Thirty Panzerturms were to reach Italy by July 1, the order stated, and one hundred steel shelters (most capable of housing a machine-gun post or antitank gun) were also en route. Extensive tunnels were to be dug into the rocky terrain and fire embrasures carved out to protect artillery from aerial or counter-battery fire.

The Gothic Line’s front approaches were to be blocked by swaths of minefields and a six-mile-deep obstacle zone created “by lasting demolition of all traffic routes, installations and shelters.” All civilians living within a twelve-mile area to the front of the line, and to a depth of six miles behind, were to be evacuated. About two thousand German troops were assigned to enforce this evacuation and forcibly recruit male Italians for civil labour construction teams.

On August 1, Obergefreiter Carl Bayerlein’s engineer battalion was transferred from the interior to Fano on the Adriatic coast. “Our assignment was the demolition of the coastal railway, plus coast surveillance, preparing positions and mining the coastal strip. The Gothic Line already had many bunkers, minefields and dugouts, but most of them were still under construction. Between Fano and Pesaro, as a defence against enemy landings, we laid a new kind of mine. These were made of concrete in which nails, screws and miscellaneous bits of scrap iron had been cast. They were stuck on wooden poles just above the ground and connected with trigger wires. They were to be used against landing troops, and were all painted green so as to be invisible in the grass. The effect of these mines was devastating.”

After completing their work at Fano, the parachute engineers moved northward to Pesaro, home to the Benelli motorcycle production plant and several other large industrial factories. Most of the machinery, tools, and production materials from these installations had already been stripped and transported to factories north of the Gothic Line or to Germany itself. Bayerlein’s team blew up any equipment that could not be removed.

Bayerlein was next put in command of an Italian labour group of thirty civilians and ordered to prepare some fighting positions at the very front of the Gothic Line. The heat and bugs were terrible. Mosquitoes posed a particular hazard. The German soldiers slept under mosquito netting at night and took Atabrine to ward off malarial infection.

More threatening than the hovering mosquitoes were the Allied fighter-bombers that circled high overhead searching for prey. Any detected vehicle or work party was bombed or strafed. Bayerlein’s Italian workers apparently feared being killed by the Allied planes more than being shot by him, for within a week he had only eight men left. The rest had run away one by one when his back was turned. Confiscating the identity papers of the next batch of rounded-up civilians stopped further desertions.

The Allied bombing not only disrupted the rate of work on the line, but also destroyed much that had been completed. When one fighter-bomber attacked a minefield, its bombs detonated hundreds of the mines that had taken days to plant. Nearby, Bayerlein’s party was constructing a dugout in the side of a sandy hill. Suddenly Bayerlein “heard a howling in the sky, and when I looked up, there was a fighter-bomber diving on us. At the last moment, I was able to push two men inside the dugout, and I finally found cover. Already the cannon were hammering away. The projectiles struck the earth right above the entrance—it was work made-to-measure.” When the attack ended, the Italians immediately fled en masse, despite Bayerlein’s possession of their identity papers.

Meanwhile, other German and Italian labour and engineering teams worked on. By August’s end, Tenth Army’s sector of line, stretching from just north of Vicchio east to Pesaro, boasted 2,375 machine-gun posts; 479 antitank gun, mortar, and assault-gun positions; 3,604 dugouts and shelters that included 27 caves; and 16,006 riflemen’s positions that consisted of embrasures constructed of fallen trees and branches. The Germans had also laid 72,517 Teller antitank mines, 23,172 S-mines, 73 miles of wire obstacles, and dug 9,780 yards of antitank ditches. Only four Panzerturms, however, were complete. Another eighteen were under construction and seven more planned. Eighteen of forty-six smaller tank gun turrets mounting 1- and 2-centimetre guns were ready. While twenty-two steel shelters were under construction, none was as yet complete.