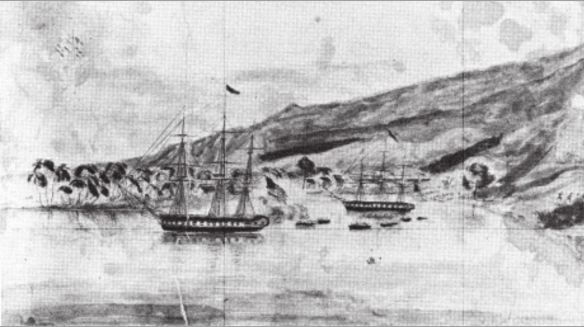

The destruction of Mukkee by the Columbia (left) and the John Adams.

Even before the Peacock’s return to the United States, signs that the East India Station was likely to become permanent were not wanting. Because the nation was prospering economically, the national debt was paid in full in 1836 and a surplus then began to accumulate in the U.S. Treasury. A near approach to war with France over spoliation claims remaining from the period of the French Revolution had focused attention on the paucity of American military and naval strength, especially the latter; as a result, the majority Democratic party began to weaken its traditional opposition to increased naval expenditures. Pointing out that the American merchant marine was second only to that of Britain, a congressional committee emphasized its vulnerability in time of war and asserted that “the interest, the honor, and even the safety of our country” required a sufficient naval force. The committee then recommended the numbers and types of warships that should be assigned to distant stations, including an East India Squadron. To be sure, recommendation and practice are quite different things, and the committee’s advocacy by no means guaranteed the permanence of the East India Station. But it was indicative of a favorable climate of opinion, which would facilitate the continuation of the station when a pressing need became apparent in the course of the next squadron’s cruise.

Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson offered the East India command to Captain George C. Read, who had earlier refused the force which sailed under Master-Commandant David Geisinger because it was not suitable for one of his rank. Assured that he would sail as a commodore on this occasion, Read went to Norfolk to prepare his vessels, the new frigate Columbia and the sloop of war John Adams, for sea. Dickerson had specified that they depart in three months, but nine months elapsed before the squadron sailed.

Two problems contributed to the delay. Commodore Read had great difficulty in manning the Columbia—seamen were in short supply in the vicinity of Norfolk, and it may be that stories of the unhealthiness of the Far East gained greater credence after the Peacock’s return to the navy yard at Norfolk. The frigate finally received an adequate number of men in January 1838 and dropped down to Hampton Roads preparatory to sailing. Then the discovery of dry rot in her stem forced her to return to Norfolk for repairs, which were slowed by unusually cold weather. So it was that the second East India Squadron did not leave the United States until 6 May 1838, nearly six months after the first had returned.

Having made the usual visits to Rio de Janeiro, Muscat, and Bombay, the two warships were at Colombo, Ceylon, when Commodore Read heard that Sumatrans had recently killed or wounded several seamen on board the American merchantman Eclipse, from which they had stolen a large sum in Spanish dollars and several chests of opium. Departing hurriedly on 2 December, the squadron made an eighteen-day passage to the west coast of Sumatra where inquiries revealed that those principally responsible belonged to the town of Mukkee, while others who had been involved resided at Quallah Battoo and Soo Soo.

When the squadron arrived at Quallah Battoo, the village rajah promised to bring the malfeasants on board within two days. He failed to do so, whereupon the Columbia and the John Adams came to anchor close inshore with springs on their cables. Bringing their broadsides to bear, they celebrated Christmas Day with a thirty-eight-minute bombardment of the forts. After returning the fire with three ineffectual shots, the forts showed the white flag. Read thought it unwise to send a landing party to complete their destruction; but he kept his ships at their anchorage until 29 December lest Quallah Battoo gain an erroneous impression of the efficacy of its defense.

Mukkee was next. The frigate sent an officer to require that the guilty individuals from there be delivered to him within two days, but his efforts were in vain. Indeed, the attitude of the rajahs led Read to believe that they would resist forcibly. On the morning of 1 January 1839, the two vessels were towed and warped into position just off the town, whence they opened a deliberate fire while a landing force prepared to disembark. The John Adams’s Commander Thomas W. Wyman led 320 sailors and marines from both companies to the beach where they formed up for an assault on the forts. Covered by the ships’ fire, they moved forward, only to find the forts and town alike deserted. All were put to the torch, and then the landing force was reembarked.

Soo Soo remained to be punished, but Commodore Read found its people so inoffensive and its fortifications so pathetically weak that he merely exacted a promise that American ships and seamen in the vicinity would be protected. While the Columbia was watering ship there, rajahs from other ports came on board to assure the commodore of their friendship and their desire that the pepper trade should continue. Obviously the destruction of Mukkee had made an impression.

The squadron weighed anchor on 7 January and beat through Great Channel into the Strait of Malacca, pausing at Penang and then standing on to Singapore. Here, Commodore Read learned that the China trade had been interrupted, but the news did not cause him to hurry on to Macao. His vessels had spent most of the past nine months under sail, and a mild form of smallpox and dysentery had plagued their companies—indeed, the Columbia had lost twenty men since leaving Rio de Janeiro. Thus, Read elected to await the change of monsoon at Singapore, from which his ships finally sailed on 28 March.

Meanwhile, the situation of foreigners in China was becoming critical, due to the traffic in opium. Import of the narcotic had been made illegal by imperial edict in 1800. Nonetheless, because it was one of the few items for which Western merchants could find a Chinese market, the quantity sent to China from India and Turkey grew steadily. Periodic reports that opium importation would be legalized caused its production to be increased; nor was there any inclination to destroy the surplus of opium when the edict was not rescinded. Thus, opium smuggling had become an ever greater part of the China trade. Those involved in this traffic salved their consciences with the arguments that the drug was really no more dangerous to its users than alcoholic beverages were to Westerners and that smuggling could be carried on only with the connivance of Chinese officials, whose responsibility it actually was.

Whether or not the Chinese government agreed, it took a decisive step to end the opium trade early in 1839 by appointing Lin Tŝe Hsü high commissioner for the Canton region with especial powers to suppress smuggling of the drug. Lin proceeded quickly and effectively by demanding that all opium be surrendered immediately, enforcing his demand by stopping trade, ordering Chinese servants to leave the factories, and detaining sixteen foreign merchants as hostages. Meanwhile, the factories were virtually besieged by thousands of Chinese.

The Reverend Dr. Elijah C. Bridgman, who had founded the first American mission in China in 1830, was among those at Canton. He expressed the hope that the traffic in opium would never recover, blaming it for the fact that “our little community here have been held these two months in painful—fearful suspense. Nor does the prospect brighten.” His companion, the missionary-printer S. Wells Williams, lashed out at a trade which “was draining the country of its wealth, and giving in exchange death & disease; a drug so noxious that not one of its advocates would consent to use it at all, while they say it does the Chinese no harm.”

This was the situation when the USS Columbia let her anchors go in Macao Roads on 27 April 1839. Peter W. Snow, U.S. consul at Canton, lost no time in acquainting Commodore Read with the facts, adding that two of the hostages were American citizens. However, Snow urged forbearance because the hostages and the occupants of the factories would almost certainly be killed before the frigate could force her way upstream to rescue them. In short, Read could only await developments and be ready to protect the Americans in Macao should the Chinese attack that city.

In due course, the merchants decided to surrender the opium to Lin, who promptly had it destroyed. The British and most of the other foreigners then withdrew to Macao, but the Americans remained in their factories in the expectation that trade would soon be resumed. However, the Chinese demand that the merchants promise not to engage in opium smuggling on pain of confiscation of ships and cargoes and of death penalties for those involved in such activity, continued to present an obstacle, the last penalty being particularly abhorrent to the Americans.

Commodore Read noted with concern that a number of British merchantmen in Macao Roads had opium in their cargoes, and he was certain that it would be landed somewhere in China, perhaps from ships flying the American flag. How to prevent this, he was not sure—the smuggling vessels could not simply be driven offshore because they would return as soon as the warships left the area. If they were seized, the problem of their disposal would remain, because technically smugglers were not breaking any American law. He could only hope that none of his countrymen were “so wicked” and, if perchance they were, at least that their vessels would show no colors while engaged in smuggling.

So the East India Squadron rode at anchor in Macao Roads, showing the flag and doing nothing more. When a small boat under American colors was attacked without provocation by Chinese in Macao harbor, Read urged Consul Snow to demand that the assailants be punished. The consul demurred on the ground that no American had been killed; the serious injury of several of those embarked did not justify a protest in such uncertain times. Read, powerless because his presence was not recognized by the Chinese, could only observe that “this is a most awkward situation to be placed in. . . .”

The weather was no help. Incessant rain, which began early in June, caused the flagship’s binnacle list to soar. Ninety men were ill, many of dysentery, of which eleven had died since the squadron left Singapore. There seems to have been no thought of setting up a hospital ashore; perhaps the fear of spreading the smallpox that had been in the ship since the beginning of the cruise kept the sick from being landed.

Trade began again in July, with the merchants certifying that they would not engage in opium smuggling. The death penalty remained, but Read thought that could be overcome if orders were given to American warships on the scene to retaliate for any such executions—the threat of reprisal alone would be enough to deter the Chinese authorities. He did not condone the opium trade; rather he feared that innocent foreigners would be victims of summary trial and punishment.

Representatives of the American commercial houses had already sent a memorial to the Congress explaining their situation, piously expressing their strong opposition to a renewal of the drug traffic, and asking that their problems be resolved by treaty. They thought a treaty could be obtained easily without resort to force if a fleet of British, French, and American warships were sent to Chinese waters. Should the U.S. government prefer not to become involved in Oriental affairs to that extent, the memorialists submitted the necessity of appointing an agent or commissioner to oversee American interests in China and of maintaining constantly a naval force to protect a commerce of greater importance than that with Latin America.

Meanwhile, the merchants tried to keep the East India Squadron in their vicinity, at least until Anglo-Chinese difficulties had been worked out. Read had written earlier that, if the expected hostilities occurred, it would be well to have a “respectable” number of men-of-war on hand to assure that the United States shared in any commercial benefits accruing to Britain as a result of the conflict, and he was aware that British blockaders had shown slight respect for neutral rights on occasion. But three more of the Columbia’s men had died, while another 120 were ill. The plight of the John Adams was almost as bad, and the surgeons believed that the ravages of dysentery would cease only when the vessels were well away from Chinese waters. In addition, the commodore had received orders to investigate a disturbance in the Society Islands. Thus, he turned a deaf ear to the entreaties of the merchants and made preparations to sail as soon as a supply of bread could be obtained.

The frigate and sloop of war weighed anchor, homeward-bound on 6 August. Old China hands had assured Read that typhoons were unknown in years as rainy as 1839; therefore, the Columbia’s oldest sails had been bent as she prepared for sea. But the old hands were wrong. A “violent tempest” struck just after nightfall, when the squadron was only about thirty miles offshore, blowing the frigate’s threadbare sails out of the boltropes before they could be furled and driving her toward the coast at an alarming rate. Although the more weatherly John Adams fared better, both vessels welcomed the change of wind direction and force which enabled them to gain an offing after thirty-six hours of buffeting. No more storms were encountered, but the vessels spent ten weary weeks tacking against easterly winds before reaching Honolulu. The meager supply of fresh provisions obtained at Macao was consumed well before that, so scurvy combined with dysentery to claim thirty more men from the two ships’ companies in the course of the passage.

From Honolulu, the squadron sailed to Tahiti and thence to Callao, where Read heard that the British had proclaimed a blockade of Canton. Refusing to believe that this blockade would endanger American interests, he took his vessels around Cape Horn and arrived in Boston in June 1840.

One might expect that the news of the Anglo-Chinese conflict popularly known as the Opium War and of the British blockade of Canton would have led the U.S. Navy Department to dispatch additional force to the Far East immediately, especially since the China merchants, heretofore aloof, had urged the necessity of such support. Yet those merchants who had watched the Columbia and the John Adams stand out of Macao Roads in August 1839, would wait almost three years before men-of-war flying their country’s flag again appeared off the Portuguese city.

This interval can be explained in part by changes in U.S. diplomatic, economic, and political situations. The omens that seemed to augur well for naval expansion during President Jackson’s second term had proven false—amicable settlement of the controversy with France removed the principal reason for enlarging the Navy, and the Panic of 1837 converted the Treasury surplus into a deficit within a short time, effectively curtailing naval appropriations. Moreover, President Martin Van Buren was a placid individual once quoted to the effect that the United States needed no navy, while his secretary of the navy, James K. Paulding, enjoyed his greatest reputation in literary circles.

But it was not intended to leave the Far East without a squadron for so lengthy a period. The frigate Constellation, at forty-three the oldest ship in the U.S. Navy, and the sloop of war Boston were fitting out in the autumn of 1840, the former at the Boston Navy Yard. Commodore John Downes, the commandant of the navy yard, had orders to sail in the Constellation as commander in chief of the East India Squadron. Downes was in his fifty-fifth year and his enthusiasm at the prospect of a lengthy cruise in the Far East dwindled, especially after the Columbia’s losses to dysentery and other ills became known. He decided to remain at the Boston yard, so Paulding chose a slightly younger man, Captain Lawrence Kearny, then commanding the Potomac, the flagship of the Brazil Squadron.

Commodore Lawrence Kearny

Soon after Kearny hoisted his broad pennant in the Constellation at Rio de Janeiro in February 1841, he wrote to complain about his flagship’s condition and enclosed a formidable list of defects. George E. Badger, the new secretary of the navy, referred the complaint to Commodore Downes, who responded that the frigate had been prepared for sea under the assumption that he would sail in her “. . . & in my opinion, I never saw a ship better fitted from any of our dockyards, than was the Constellation.” Badger had to accept this reply because the Constellation was well on her way to the station, but Kearny’s experience with her cast doubt upon the validity of Downes’s statement.

The flagship lay at Rio de Janeiro for a month while her company made good some of her defects, and then began a leisurely passage which ultimately brought her and the Boston to Macao on 22 March 1842, more than a year after she had departed the Brazilian city. The frequent need for repairs explains the delay only in part; Kearny seems to have felt no need for haste despite his orders to the contrary.

Those orders also emphasized that China was the most important part of his station and made the protection of Americans and their property his first responsibility, although the Chinese were to be told that the squadron had been sent to prevent opium smuggling by American citizens or others under the U.S. flag. If Kearny’s protestation of friendship for the Chinese led them to seek his support against a legal British blockade, he would reply that he could do so only on direct orders from his government. In fact, international law required the recognition of legal blockades by all neutral shipping; however, if Kearny had been disposed to ignore the blockade, he had to face the reality that his force consisted only of an elderly frigate and a sloop of war, while the British had twenty-three warships in Chinese waters.

USS Constellation

At any rate, there was no blockade of Canton when the Constellation and the Boston stood into Macao Roads, for hostilities in that vicinity had been ended almost a year earlier. Superior weaponry, tactics, and discipline had enabled small forces of Britons to disperse many times their number of Chinese and to destroy the fortifications; trade was then resumed. Even as British units were conducting offensive operations against the Chinese Empire farther northward, merchant vessels under British colors were allowed to trade at Canton without interference or discrimination on the part of Chinese authorities.

Commodore Kearny soon had occasion to implement that portion of his orders relating to the smuggling of opium. A shipping report in the Hong Kong Gazette listed an American vessel laden with opium, whereupon Kearny wrote the U.S. consul at Canton desiring him to publicize and make known to Chinese authorities the fact that Americans and their ships seized while engaged in the opium trade could expect no assistance from the East India Squadron because the U.S. government did not approve of the narcotic smuggling. There Kearny stopped—non-interference with the traffic obviously was not the same as its suppression, but more than a year elapsed before he took any further action.

Soon after the squadron came to anchor in Macao Roads, the American vice-consul transmitted a request from several merchants that redress be sought for incidents which had occurred almost a year before. The principal complaint concerned Chinese soldiers firing on a boat belonging to the merchantman Morrison while it was en route from the factories to Whampoa. One American had been killed and his fellows were wounded and captured. At least one other case of an imprisoned boat crew was cited—all had been released within a short time, but Chinese officials had ignored all damage claims. The Canton Register did what it could to force the commodore’s hand by announcing that the Constellation and the Boston would, if necessary, “vindicate the honor of the U.S. flag by exacting from the Chinese a most heavy retribution for their most treacherous violation of international law.” But Kearny would adopt a belligerent stance only as a last resort, nor was he interested in obtaining anything more than a fair settlement.

U.S. warships arriving off Macao or Lintin Island had been accustomed to receive through the consul—and to ignore—orders from Chinese officials to depart forthwith. No such orders were forthcoming for the Constellation and the Boston, leading Kearny to hope that this might indicate a changed attitude on the part of the authorities—perhaps he would be able to communicate with them directly rather than through the agency of the merchants as his predecessors had had to do. And, since there was no protest against his squadron’s presence in the usual anchorage, might it not sail up to Whampoa without arousing Chinese displeasure? The commodore decided to seek an answer to that question by sailing up the Canton River. To indicate that he had no intention of trying to force a passage, he sent the Boston to Manila while the frigate alone tested the Chinese disposition.

Receiving Dr. Bridgman on board to serve as interpreter, the flagship weighed anchor on 11 April and stood up the estuary, into the Boca Tigris, past the Second Bar, and on to the First Bar. There she paused while Kearny wrote the consul in Canton, asking him to inform Chinese authorities that the Constellation sought an anchorage convenient for replenishing her provisions and communicating with Chinese officials. When no prohibition of further movement was received, the frigate sailed up to the merchant ship anchorage at Whampoa, where she stayed for seven weeks. The Boston rejoined the flag early in May, and again the Chinese made no protest.

Understandably elated at his success in gaining an anchorage where foreign warships had never before been permitted, Kearny next tried to open direct communication with Chinese officialdom. His efforts were rebuffed at first, but when he argued that letters delivered by a commissioned officer could be received properly only by another of equivalent rank, the protocol-conscious Orientals had to agree. Thereafter, direct communication became customary.

Chinese amiability extended to the incidents of which the American merchants had complained to Kearny. Explaining that the soldiers involved had thought the American small craft were British boats, the viceroy at Canton asked the commodore to decide the amount of damages to be paid, although payment would have to be made by the Hong merchants who alone were allowed to trade with foreigners. Kearny accepted this duty and did not require that the guilty individuals be punished.

Settlement of the claims was endangered when a Chinese fort fired on one of the Constellation’s boats. Kearny’s request for an explanation brought the response that the boat was taking soundings in the vicinity of a barrier and that the garrison had tried to warn it off. When the warnings were ignored, the boat had been fired on in the belief that it had no right to show the American flag. The officer in charge of the boat admitted that its approach to the barrier might have been thought provocative; whereupon Kearny reprimanded him and declared the incident closed.

Having no further reason to stay at Whampoa, the squadron dropped down to Macao in June. When sickness appeared in both ships, they ran over to the harbor between the island of Hong Kong and the mainland, some forty miles to the eastward of Macao. This had become the anchorage for merchant shipping when the Canton trade was halted in 1839, and Britons had established a permanent settlement there. Apparently the change of locale was effective, for neither vessel reported any fatalities and both crews were restored to health in a short time.

Commodore Kearny was dubious about the British military situation vis-à-vis China. Sickness had made great inroads into the effectiveness of the 12,000 Britons available for service, and he thought the strategy of dispersing these troops among widely separated points made it unlikely that a significant victory could be won at any one. Moreover, the Anglo-Chinese conflict was proving to be immensely costly; Kearny heard that the East India Company had had to borrow money at 10 percent and was anxious that the war should come to an end.

Come to an end it did. Little more than two weeks after Kearny had expressed his doubts, Sir Henry Pottinger’s army moved on Nanking, whereupon the Chinese recognized the futility of further fighting and agreed to negotiations. But the peace treaty was more nearly dictated than negotiated, for the British received virtually everything they wished. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain outright, and five so-called treaty ports—Canton, Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and Shanghai—were opened to British trade. A consulate could be established at each, and merchants would be allowed to reside permanently in these ports with their families. Trade could be carried on with any Chinese merchants under a fixed tariff on imported goods. The Chinese had to pay a sum that included the value of the destroyed opium as well as the expenses of the British military expeditions, but the Treaty of Nanking made no reference to the status of the opium trade.

Commodore Kearny obtained three copies of the treaty in late September. Two he sent to the United States by separate messengers taking the overland route to Western Europe; the Boston took the third across the Pacific to Mazatlán, Mexico—from there it would be forwarded to Washington.

Meanwhile, the commodore himself undertook to gain rights for American commercial interests that were similar to those won by the British. A brief letter to the viceroy at Canton called the viceroy’s attention to Kearny’s desire while emphasizing that the naval officer did not wish to force the issue. Nor was it necessary to do so; the viceroy replied promptly that merchants of all nations had received equal treatment at his hands in the past and he had no intention of altering this policy. As soon as the details of a commercial treaty with Britain had been worked out, he would make recommendations to Peking with regard to trade regulations in general and “decidedly it shall not be permitted that the American merchants shall come to have merely a dry stick.”

Kearny believed that he could not require any additional assurance. Chinese treatment of Americans as citizens of a most-favored nation could be guaranteed only by treaty, and that he was not authorized to negotiate. He had already urged the dispatch of a commercial agent not connected with any of the commercial houses and supported by an impressive force of warships; until these warships could arrive, the American merchants would have to trade on whatever terms the Chinese saw fit to give them.

Kearny intended to sail on 1 November to visit Australia, New Zealand, and various South Pacific islands in order to show the flag and give any assistance which American whaling ships frequenting those waters might need. Although this “whale fishery protection” duty had been designated an important part of his squadron’s mission, second only to that of looking after U.S. interests in China during the Opium War, it was never carried out. The announcement of the Constellation’s intended departure brought a strong protest from Consul Snow at Canton, who insisted that the frigate remain in Chinese waters at least until mid-February. “You . . . know the prompt and immediate action by this Govt on communications from the Commander of an American Squadron.” The commodore concluded that Snow was correct; since he had no intelligence of conditions requiring his presence elsewhere, he would stay.

Kearny’s decision probably did not elicit an enthusiastic response from the Constellation’s company, one of whom had just written that “the extremely dull time we have had since we arrived in China has made everyone low spirited.” The frigate would spend a week or so at Macao, then run up to the Boca Tigris for a time, thence to Hong Kong; but the movement from one anchorage to another did little to relieve the boredom. Late in November, the flagship went to Manila for a month, which must have been a welcome interlude.

Back at Macao, the commodore received news of a mob attack on the Canton factories and a request from Augustine Heard and Company for assistance in obtaining reparation for damages suffered in the riot. After conferring with Vice-Consul James P. Sturgis at Macao, Kearny took the Constellation up to Whampoa, whence he went on to Canton.

During the five weeks he spent there, the commodore got the viceroy’s assurance that the damages would be made good, and the latter added that the death of a Chinese official had delayed the formulation of trade regulations. The viceroy suggested that when these regulations had been drawn up, perhaps Kearny would meet with imperial commissioners to decide on the specific rules to govern Sino-American trade. To this, the naval officer could reply only that his government would require terms identical to those given other countries and that, although he was not empowered to negotiate a treaty, the United States doubtless would send an envoy for that purpose should the Chinese be willing to receive him. But the Chinese sought no treaties; the viceroy assured Kearny that they were unnecessary and foreign to Chinese tradition.

By the time the Constellation dropped down the Canton River again, mid-February was long past, but she continued her periodic shuttling between Macao, Hong Kong, and the Boca Tigris until late April. Reports that vessels flying the American flag were involved in the revived opium trade led the commodore to seek information on this subject from Sturgis and others. He learned that several schooners, supposedly American, were actually serving British interests, and this news appeared to infuriate him. He prepared a strongly worded statement reiterating his squadron’s orders to prevent opium smuggling under American colors and declaring himself ready to enforce those orders.

Nonetheless, Kearny seemingly had no intention of acting. After sending this statement to Sturgis, he sailed for Manila. There he wrote the secretary of the navy that his recent warning would suffice to prevent illegal use of the flag; thus he need not touch at the area where the incidents were reported.

The Constellation embarked a five months’ supply of provisions from those deposited there for the squadron’s use. Unfortunately, cholera was making one of its periodic visitations to Manila, and a few of the frigate’s men contracted the malady. The Constellation departed in haste, but not before two men had died; two more men succumbed soon afterward.

Her homeward passage was of short duration. The water obtained at Manila proved to be impure, so a fresh supply had to be sought. Macao during the “sickly season” might be fatal to some of those on the binnacle list; therefore, the flagship sailed up to Amoy, southernmost of the treaty ports save Canton.

At Amoy the opportunity to deal a blow to the opium traffic presented itself. The schooner Ariel, one of those named by Sturgis as improperly registered, had just landed a cargo of opium. Kearny sent a boarding party to take possession of the vessel, forced her master to discharge the money and camphor he had received in payment for the drug, and ordered him to take her to Macao for further action by Sturgis, explaining that she was so heavily sparred as to be unseaworthy—hence she could not be sent to the United States for trial. It should be noted that the Ariel was seized, not because she was a smuggler—no U.S. law forbade smuggling opium into China—but because she had no right to the American flag she was accustomed to fly. The commodore promised the same treatment to any of the schooner’s fellows he might encounter—an idle threat because the Constellation got underway for Honolulu on 22 May 1843, just three days after ordering the Ariel to Macao.

Lawrence Kearny has generally been recognized as an able “sailor diplomat” whose ability as a diplomat was largely responsible for the extension of the commercial advantages obtained in China by the British to other nations. In addition, he has been cited for making the first real effort to suppress opium smuggling. However, one doubts that the commodore himself would have claimed much credit for either. He practiced “jackal diplomacy” to the extent that he requested for his nation a share of the spoils won by the British lion in combat; had Britain or China opposed his request, he was powerless to do more. Kearny had the intelligence to grasp opportunities—he did not create them. His steps to curb opium smuggling were innocuous in the extreme and designed mainly to mislead Chinese officials; but this conduct was in accordance with his orders.

This is not to say that Commodore Kearny deserves no credit. Rather he should be recognized for his feat in keeping his men unusually healthy and reasonably contented during a lengthy cruise on an unhealthy and “very disagreeable station.” The commodore attributed their good health mainly “to the plentiful supply of good wholesome water and provisions” and the men themselves expressed their appreciation of Kearny’s “mild mode of discipline” which had made the frigate “the happiest ship that ever left the United States.”