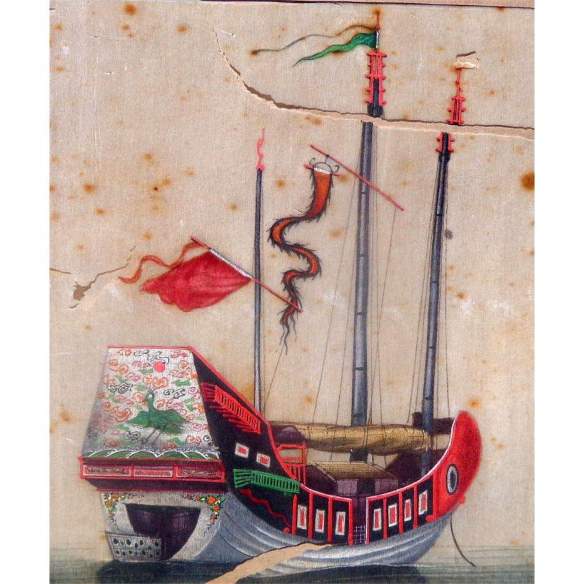

Junk is a type of ancient Chinese sailing ship that is still in use today. Junks were used as seagoing vessels as early as the 2nd century AD and developed rapidly during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). They evolved in the later dynasties, and were used throughout Asia for extensive ocean voyages. They were found, and in lesser numbers are still found, throughout South-East Asia and India, but primarily in China. Found more broadly today is a growing number of modern recreational junk-rigged sailboats.

The term junk may be used to cover many kinds of boat—ocean-going, cargo-carrying, pleasure boats, live-aboards. They vary greatly in size and there are significant regional variations in the type of rig, however they all employ fully battened sails.

The construction of junks has been distinguished from the characteristics of traditional western vessels by several features: the unbattened sails on masts that employ little standing rigging, the presence of watertight bulkheads to minimize the consequences of a hole in the hull, the use of leeboards, and the early adoption of stern-mounted steering rudders. The historian Herbert Warington Smyth considered the junk as one of the most efficient ship designs, stating that “As an engine for carrying man and his commerce upon the high and stormy seas as well as on the vast inland waterways, it is doubtful if any class of vessel… is more suited or better adapted to its purpose than the Chinese or Indian junk, and it is certain that for flatness of sail and handiness, the Chinese rig is unsurpassed.”

The structure and flexibility of junk sails make the junk fast and easily controlled. The sails of a junk can be moved inward toward the long axis of the ship. In theory this closeness of what is called sheeting allowed the junk to sail into the wind. In practice, evidenced both by traditional sailing routes and seasons and textual evidence junks could not sail well into the wind. That is because a rig is dependent on its aerodynamic shape, the shape of the hull which it drives, and the balance between the centre of effort (the centre of drive) of the sail plan and the centre of resistance against the hull. In the typical junk these were both ill-adapted to windward work because, put simply, junks were neither intended to nor designed to work to windward.

The sails include several horizontal members, called “battens”, which in principle could provide shape and strength but in practice, because of the available materials and technology, did neither. Junk sails are controlled at their trailing edge by lines much in the same way as the mainsail on a typical sailboat, but in the junk sail each batten has a line attached to its trailing edge where on a typical sailboat a single line (the sheet) is attached only to the boom. The sails can also be easily reefed to accommodate various wind strengths, but there was traditionally no available adjustment for sail shape for the reasons given to do with traditional materials. The battens also make the sails more resistant than other sails to large tears, as a tear is typically limited to a single “panel” between battens. In South China the sails have a curved roach especially towards the head, similar to a typical balanced lug sail. The main drawback to the junk sail is its high weight caused by the 6 to 15 heavy full length battens. With high weight aloft and no deep keel, junks were known to capsize when lightly laden due to their high centre of gravity. The top batten is heavier and similar to a gaff. In principle junk sails have much in common with the most aerodynamically efficient sails used today in windsurfers or catamarans. In practice, because of the comparatively low tech materials, they had no better performance characteristic than any other contemporary sail plan, whether western, Arab, Polynesian or other.

The sail-plan is also spread out between multiple masts, allowing for a comparatively powerful sail area, with a low centre of effort, which reduces the heeling moment. However, a thoughtful analysis of these multiple masts indicates that only two or so were actually the main ‘driving’ sails. The others were used to try to balance the junk—that is, to get it to more or less steer itself along the chosen course. This was necessary because the Chinese stern hung rudder, in origin a modified centreline steering oar, whilst extremely efficient, was comparatively mechanically weak. The large forces that a sailing vessel can place upon its rudder were known to rip rudders from their relatively weakly constructed mountings (many trading junks carried a spare rudder), so using the sail plan to get the junk to steer itself, reducing the loads on the rudder, was an ingenious development.

Flags were hung from the masts to bring good luck and women to the sailors. A legend among the Chinese during the junk’s heyday regarded a dragon which lived in the clouds. It was said that when the dragon became angry, it created typhoons and storms. Bright flags, with Chinese writing on them, were said to please the dragon. Red was best, as it would induce the dragon to help the sailors.

Classic junks were built of softwoods (although after the 17th century of teak in Guangdong) with the outside shape built first. Then multiple internal compartment/bulkheads accessed by separate hatches and ladders, reminiscent of the interior structure of bamboo, were built in. Traditionally, the hull has a horseshoe-shaped stern supporting a high poop deck. The bottom is flat in a river junk with no keel (similar to a sampan), so that the boat relies on a daggerboard, leeboard or very large rudder to prevent the boat from slipping sideways in the water. Ocean-going junks have a curved hull in section with a large amount of tumblehome in the topsides. The planking is edge nailed on a diagonal. Iron nails or spikes have been recovered from a Canton dig dated to circa 221 BC. For caulking the Chinese used a mix of ground lime with Tung oil together with chopped hemp from old fishing nets which set hard in 18 hours, but usefully remained flexible. Junks have narrow waterlines which accounts for their potential speed in moderate conditions, although such voyage data as we have indicates that average speeds on voyage for junks were little different from average voyage speeds of almost all traditional sail, i.e. around 4–6 knots. The largest junks, the treasure ships commanded by Ming dynasty Admiral Zheng He, were built for world exploration in the 15th century, and according to some interpretations may have been over 120 metres (390 ft) in length, or larger. This conjecture was based on the size of a rudder post that was found and misinterpreted, using formulae applicable to modern engine powered ships. More careful analysis shows that the rudder post that was found is actually smaller than the rudder post shown for a 70’ long Pechili Trader in Worcester’s “Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze”.

Another characteristic of junks, interior compartments or bulkheads, strengthened the ship and slowed flooding in case of holing. Ships built in this manner were written of in Zhu Yu’s book Pingzhou Table Talks, published by 1119 during the Song Dynasty. Again, this type of construction for Chinese ship hulls was attested to by the Moroccan Muslim Berber traveler Ibn Batutta (1304–1377 AD), who described it in great detail (refer to Technology of the Song Dynasty). Although some historians have questioned whether the compartments were watertight, most believe that watertight compartments did exist in Chinese junks because although most of the time there were small passage ways (known as limber holes) between compartments, these could be blocked with stoppers and such stoppers have been identified in wrecks. All wrecks discovered so far have limber holes; these are different from the free flooding holes that are located only in the foremost and aftermost compartments, but are at the base of the transverse bulkheads allowing water in each compartment to drain to the lowest compartment, thus facilitating pumping. It is believed from evidence in wrecks that the limber holes could be stopped either to allow the carriage of liquid cargoes or to isolate a compartment that had sprung a leak.

Leeboards and centerboards, used to stabilize the junk and to improve its capability to sail upwind, are documented from a 759 AD book by Li Chuan. The innovation was adopted by Portuguese and Dutch ships around 1570. Junks often employ a daggerboard that is forward on the hull which allows the center section of the hull to be free of the daggerboard trunk allowing larger cargo compartments. Because the daggerboard is located so far forward, the junk must use a balanced rudder to counteract the imbalance of lateral resistance.

The rudder is reported to be the strongest part of the junk. In the Tiangong Kaiwu “Exploitation of the Works of Nature” (1637), Song Yingxing wrote, “The rudder-post is made of elm, or else of langmu or of zhumu.” The Ming author also applauds the strength of the langmu wood as “if one could use a single silk thread to hoist a thousand jun or sustain the weight of a mountain landslide.”

Ching Shih(also known as Cheng I Sao) had over 300 Junks under her command, manned by 20,000 to 40,000 pirates. With a fleet so large, she was a large threat to the Chinese, who had not been developing a better navy. After Ching Shih retired, the Chinese Navy had continued to make the same mistake, and would cause their downfall later in the First Opium War. This is also why Chinese mariners didn’t have a good compass until the 19th century.

The Vessels

From the 9th to the 12th century, large Chinese sea-going ships were apparently developed. The first Sung emperor often visited shipyards, which produced both river and sea-going vessels. In 1124 two very large ships were built for the embassy to Korea. There is a relief carving on the Bayon temple built by Jayavarman VII in Angkor Thom in Cambodia cited in Needham. Dating from circa 1185, it pictures a Chinese junk with two masts, Chinese matting sails, and stern-post rudder. A Nan Sung scholar, Mo Chi of the Imperial University, is reported as sailing far to the north in Chhi Tung Yeh Yu. In 1161, the main fleet of the Sung navy fought a larger Jin Empire fleet off the Shandong Peninsula and won. Thus, the Southern Sung of the 12th century gained complete control of the East China Sea. There were four decades of maritime strength for the Sung (until the first decade of the 13th century), when the Sung navy declined and the Mongols started building a navy to help conquer the Sung. In 1279, the Mongol Khubilai Khan had conquered the Sung capital and then his quickly created fleet chased a large Sung junk with the renegade Sung court and the last Sung prince, who leaped into the water and drowned.

The Yuan (Mongol) dynasty of the 13th and 14th centuries maintained the large fleet, sent emissaries to Sumatra, Ceylon, and southern India to establish influence, and Yuan merchants gradually took over the spice trade from the Arabs. It was the Yuan ships of this era that Marco Polo saw and reported, consisting of four-masted ocean-going junks with sixty individual cabins for merchants, up to 300 crew and watertight bulkheads. The Yuan dynasty greatly favored sea power (somewhat at the expense of lake and river combatants, which had been developing human-powered paddlewheel ships up until this period). However, while the Yuan achieved greater foreign contacts and overseas trading success, Khubilai Khan failed spectacularly in his two massive maritime expeditions against Japan (1274 and 1281), and also in expeditions against the Liu Ch’iu (Ryukyu) Islands. Initial successes of a Yuan armada against Java were followed by a forced retirement. A major feature of the Mongol rule of the Yuan dynasty was a dramatic lessening of Confucian influence in the Imperial court, and a great opening to foreign influences.

When the Manchus retook the Imperial throne and thus founded the Ming dynasty in the second half of the 14th century, the early Ming emperors inherited much of the Yuan maritime technology and policy. There were huge ocean-going warships, large ocean capable cargo ships, a regular coastal grain delivery system transporting grain from the southern provinces to the northern ones, and considerable foreign contacts, primarily in south east Asia but extending to Ceylon and India. However, two other dynamics were at work. First, the Ming dynasty was continually working to restore her native culture after a century-long of foreign rule. The Grand Canal, initially completed during the Sui dynasty (6th century AD), with a vast remodelling and extension to the new northern capital at Peking during the Yuan (13th century), was initially in disrepair due to the extensive conflict between the Yuan and Ming. The early Ming saw the rebuilding and improvement of the Grand Canal and other canals, paved highways, bridges, defenses, temples, shrines and walled cities. Second, the Ming administration was being restructured, with a resurgence of Confucian scholars as senior officials and a great development in the use of eunuchs in high office as well. These two categories of high officials were in considerable conflict throughout the Ming period. The Confucians were generally ascendant, but during the rule of the third Ming Emperor, Zhu Di, the eunuch administrators and warriors were greatly trusted and given great power. This was largely because Zhu Di was a rebel warrior prince who usurped the throne of his nephew, with an initial power base purely in the north. Many of the government ministers disapproved of his usurpation early in his reign, so Zhu Di preferred to entrust eunuchs with a large share of the business of government. Many of the eunuch administrators had been loyal retainers to Zhu Di in the frontier wars and the rebellion for decades, whereas the Confucian administrators and warrior princes had defended the old, recently defeated regime.