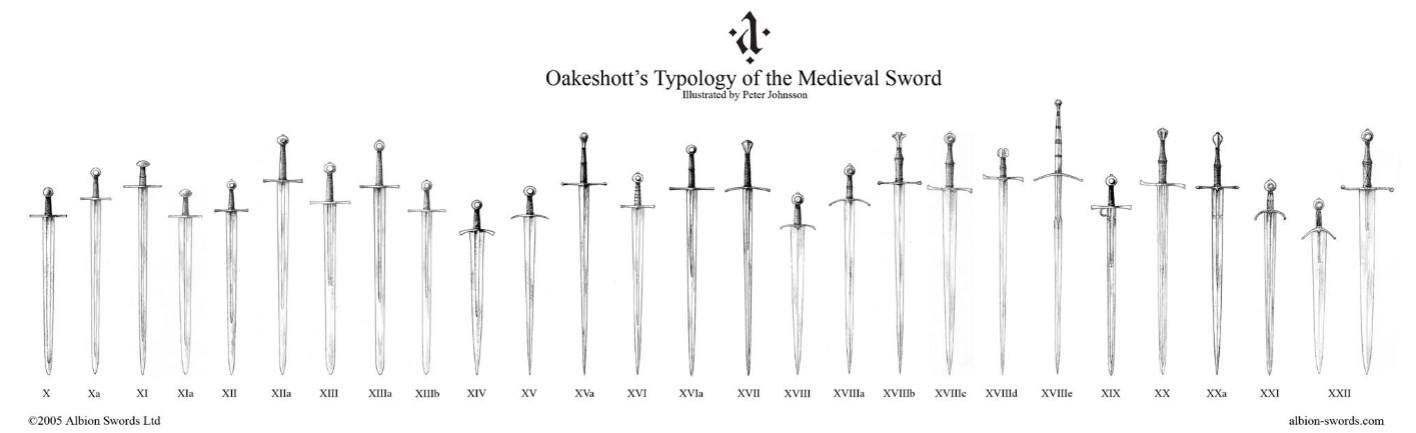

Oakeshott’s Typology of the Medieval Sword – A Summary

The medieval weapon par excellence. Iron made a significant difference, producing a thinner and more flexible weapon. The Roman sword was short and stout, primarily for thrusting. Its development probably came via the Greeks and Etruscans. Iron swords were found at La Tene on Lake Neuchatel. Styria was an important centre of manufacture. Early users were the Celts who developed the pattern-welded blade with strips of iron twisted together cold and then forged; twisted again and re-forged to the edges. The blade was then filed and burnished, leaving a pattern from the now smooth surface of twisted metal. Unlike bronze, iron was worked by forging rather than casting. Iron made possible a different structure for the sword, with a tang from the blade over which the handle could be slotted. Iron had advantages but a longer iron sword would bend and buckle if used for thrusting. Early European swords were long with cutting edges. When used by charioteers they needed length, best used with a cutting action. Much the same is true of cavalry swords. Swords from the first four centuries BC came from bog deposits in Scandinavia. Those at Nydam had pattern welded blades, about 30 inches long and mostly sharpened on both edges. A sword at Janusowice from the time of the Battle of Adrianople had a long blade and evidence of a leather scabbard. It had a large bronze, mushroom-shaped pommel. The sword at Sutton Hoo, old when buried, had a pommel decorated with gold and red garnets. It had rusted inside its scabbard, but X-rays showed it was pattern welded. The scabbard was of wood and leather.

Viking swords were outstanding in design and efficiency. What we call `Viking’ swords are common to those used over a wider area including Francia. They were of varied styles of blade and hilt. Petersen detected no less than 26 types of hilt. The hilt was formed over a tang from the blade, slotting over the guard, covering the grip, the end stopped with a pommel. The most common zv2 49 Viking pommel had three lobes but there were many variations. Most Viking swords were plain but well designed. Some were decorated with patterns of inlaid copper and brass on the hilt. Thin sheets of tin, brass, gold, silver and copper might be used. Some had a maker’s name or a firm’s name. On one lower guard is lettering Leofric me fec[it] (Leofric made me). Other names are Hartolfr, Ulfbehrt, Heltipreht, Hilter and Banto. Ulfbehrt is found quite often, for example on a sword from the Thames. The name seems a Scandinavian-Frankish hybrid. Ulfbehrt swords date from the 9th to the 11th centuries. One should probably think of most as made by `firms’, no doubt family concerns, rather than by individuals. This manufacture probably originated in the Rhineland. Another name to appear in the 10th century, though less frequently, is Ingelrii-about 20 have been identified. A sword from Sweden reads Ingelrii me fecit. One finds other inscriptions and symbols, often enigmatic, including crosses, lines, Roman numerals and runes. Some names were of owners rather than makers, for example, `Thormund possesses me’. Swords were sometimes named by their owners for example as millstone-biter, leg-biter. Viking swords became heavier from the 8th century, and in the 10th century there were design improvements. Later swords were not usually pattern welded and some were of steel, harder and more flexible. They were lighter and tougher with a more tapered blade, bringing the balance nearer to the wrist, and could be used for thrusting or cutting.

The sword became the weapon par excellence of the later medieval knight. The significance given to swords in literature, to Arthur’s Excalibur or Roland’s Durendal reflects this regard. It had symbolic value, in oath-making, dubbing, being blessed by the Church or promised to churches after the knight’s death.

Late medieval swords were shorter and less flexible. Some survive-from burials, riverbeds and in churches, including `Charlemagne’s sword’ which is probably 12thcentury, the sword of Sancho IV of Castile late 13th-century, of Emperor Albert I c. 1308 from his tomb, and of Cesare Borgia dated 1493.

Pommel

The pommel was the extreme end of the sword hilt or dagger. Swords were constructed so that the blade had a projecting tang over which the parts of the hilt were threaded. The pommel completed the hilt and held it in place, the tang being hammered over the end of the pommel. The term came from Latin for a little fruit, in French a little apple. Pommel shapes help to distinguish types of sword-Oakeshott has identified 35. Modern attempts to zv2 47 describe these shapes include cocked hat, tea cosy, scent-stopper and brazil nut. Pommels were often decorative; one from Sutton Hoo was decorated with gold and red garnets. A dagger from Paris was marked with arms on the pommel. The most common Viking pommel had three lobes. A disc-shaped pommel was popular in the later Middle Ages. After the medieval period old detached pommels proved useful for shopkeepers’ weights. (Note: the word pommel was also used for the upward projecting front of a saddle.)

Scabbard

Container for a sword or dagger. The term is from Old French, the English equivalent being sheath. It protected the blade when not in use. Wood and leather were common materials, as in the Sutton Hoo example. The inside was sometimes lined with wool so that lanolin would prevent rust. The scabbard could have a locket at the top to grip the blade just below the hilt. The scabbard could be made of cuir bouilli (leather soaked and dried). The scabbard might be attached to a baldric, worn over the shoulder, or on a belt. Several scabbards survive, A 13th-century one from Toledo is made of two thin pieces of wood covered with pinkish leather. It ends in a chape of silver, a projecting piece of metal. Oakeshott believes the chape was meant to catch behind the left leg for ease in drawing the sword. It also protected the vulnerable end of the scabbard.

Seax (Sax)

A short sword or knife with a heavy, single-edged blade wielded one-handed, associated with the Franks and Alemans. It was used by the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. Seax was its Old English name, possibly from the Saxon folk as the franciska from the Franks though it may derive from the Latin sica, a Thracian weapon. Blade types included the angle-backed shape from the 7th century. The seax varied in length from 6 to 18 inches, with 12 inches the most common. The blade usually had a tang with a hilt, like a sword. The shorter seax is sometimes called a scramasax.

Hilt

The handle or grip of a sword or dagger. Petersen detected no less than 26 types of hilt for swords of the Viking period. The hilt was formed over a tang from the blade, slotting over the guard, covering the grip, with a pommel to stop the end. The hilt was often decorated in patterns, for example with inlaid copper and brass. Thin sheets of tin, brass, gold, silver or copper might be used. Some were marked with a maker’s or firm’s name. On one lower guard is lettering `Leofric me fec[it]’ (Leofric made me), possibly meaning the hilt rather than the whole sword. The transverse piece of metal forming part of a sword hilt is the crossguard, separating it from the blade.

Falchion

Sword with a curved, sharp outer edge broadening towards the point and then tapering so that it looked boat-shaped. The blunt edge was straight. The name was from Latin falx (scythe) from its shape. It descended from the Norse seax. Its period of prominence was the 13th and 14th centuries. The faussar of 12th-century Iberia might be an early example. The falchion was used by lower ranking infantry, men-at-arms and archers. One was found at the Chatelet in Paris with the Grand Chatelet arms on the pommel. The Conyers Falchion, at Durham, was used in tenure ceremonies.

Crossguard

The transverse piece of metal that forms the first part of a sword hilt, separating it from the blade, protecting the swordsman’s hand. It was commonly made from one piece of metal with a slot in the centre fitting over the tang of the blade. It varied in shape and style, for example straight, curved, or in shapes resembling bow ties. Oakeshott has produced a list of types of crossguard, an aid to dating swords.