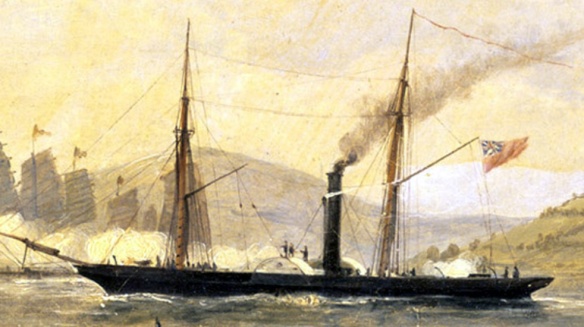

The Nemesis Steamer

British sailors towing warships toward the besieged city of Canton on 24 May 1841.

On March 13, 1841, the rest of the British fleet arrived outside Canton, and blew the Chinese ships in the harbor to pieces and knocked out the city’s cannon. During the afternoon of March 19, British marines and sailors landed near the factories, and the defenders fled without firing a shot. Many refugees were cut down during the retreat. The following day, Elliot occupied the New English factory and declared peace.

Howqua now approached Elliot, begging for a truce on behalf of General Fang. Elliot agreed and used the opportunity to restore trade and at the same time deal a partial blow to the opium trade he excoriated. The trade in tea would recommence, but any opium found aboard British ships would be confiscated. However, opium importers would no longer be arrested and punished, abolishing Lin’s death penalty.

The truce was just a feint on the part of the Chinese, who continued to mass troops outside Canton. Elliot daily saw Chinese ships bristling with soldiers sail past the English factories.

General Yang Fang, shared Qishan’s conciliatory attitude toward the invaders and urged the Emperor to allow the opium trade to continue, because he reasoned that if the British occupied themselves with making money, they would have little time and desire to wage war against the Chinese. The Emperor dismissed Fang’s advice, saying, “If trade were the solution to the problem, why would it be necessary to transfer and dispatch generals and troops?” Instead, the Emperor ordered Yang and the other two members of the triumvirate, Ishand and Longwen, to retake Hong Kong, the loss of which continued to obsess the humiliated Emperor.

Toward the end of March, 1841, Elliot and his staff decided to attack Amoy, about four hundred miles northeast of Canton, with the date set for the second week of May. Before the attack could begin, however, Elliot fell ill in Macao. Adding to his woes was intelligence that Chinese troops were massing outside Canton along warships and fireboats, while forts in the area were being repaired. Yang Fang used the presence of the troops and war machinery to urge Elliot to return to the bargaining table, by letting him know that the Chinese military forces now outnumbered the British-not much of a threat or bargaining chip considering the primitive conditions of the Chinese forces and their recent track record in battle. Elliot heeded the warning, but instead of suing for peace, he cancelled the attack on Amoy to concentrate on the armed camp that Canton had become.

On May 11, 1841, Elliot boarded the Nemesis with his wife and made for Canton. There he saw the newly repaired forts bristling with new cannon. He also noticed a parade of Chinese warships sail past the factories. Elliot sent the prefect of Canton a letter demanding that war preparations by the Chinese cease.

On May 21, 1841, Elliot ordered the British and urged the Americans to leave the factories. Only a few Americans ignored Elliot’s recommendation; the entire British population complied. In less than twenty-four hours, the foreign quarter became a ghost town. The quiet was shattered at midnight when the Chinese attacked, shelling the factories from opposite riverbanks.

Fireboats stuffed with cotton drenched in oil were launched against the British warships, which were becalmed. The Nemesis was able to steam away from danger, firing on the Chinese warships, which sought cover behind the fire ships. The fire ships missed the British vessels and crashed into the shore, where they set the city ablaze. The Nemesis fired on the forts and silenced their artillery. By the next morning, the sea battle was over. The Chinese had failed to dislodge the British.

On May 25, 1841, the Nemesis, towing seventy sailing ships teeming with two thousand troops, reached Tsingpu, two miles northwest of Canton. Tsingpu had a natural harbor from which the British could launch an attack on the northern heights of Canton. The troops and artillery disembarked. As they marched toward Canton, Chinese soldiers screamed and waved their weapons at the invaders, but didn’t attack and kept a safe distance.

On May 26, 1841, it was decided to assault a hill and tower that made up part of the wall that defended Canton. Once captured, the hill would make an excellent position for artillery, which would shell the city and force a quick surrender, the attackers were certain. The Chinese defended the hill briefly, inflicting only one casualty on the British, then fled.

The following day, May 27, at 10 A. M., a mandarin waving a white flag appeared on the wall of a nearby fort. With Thom translating, the mandarin begged for a cessation of hostilities. Through intermediaries, Hugh Gough told the mandarin that he would only negotiate with the commander of the Chinese forces in Canton, but agreed to an armistice while waiting for the officer. He never appeared, and Gough resumed preparations for an attack. Around seven the next morning, the British were about to begin shelling the city when Chinese on the nearby fort’s walls again waved white flags, but this time also bellowed Elliot’s name “as if he had been their protecting joss,” according to Edward Belcher. The real reason the defenders shouted out Elliot’s name was that they mistook a naval lieutenant climbing the hill for the Superintendent of Trade. The lieutenant carried instructions ordering the troops not to continue the attack because Elliot was already negotiating with the Chinese over the fate of Canton.

But on May 29, 1841, General Fang broke the truce and ordered his men to attack Canton with the battle cry, “Exterminate the rebels!” That same day, manned (!) fire rafts unsuccessfully tried to set fire to British ships docked at Whampoa, five miles west of Canton, while the fire rafts’ crew threw stinkpots at the enemy vessels and attempted to board them with grappling hooks. Chinese troops also invaded the foreign factories, looting, then tearing them down. British ships sailed up the Pearl River and began to bombard the walls of Canton. Elliot decided not to invade the city because his forces, decimated by dysentery, had dwindled to twenty-two hundred men, while the occupiers of Canton numbered more than twenty thousand.

Another truce was agreed to, with the Chinese promising to pay a $6 million ransom within seven days and the British promising not to sack the city if the money was paid. The British government was at last seeing a “profit” in its war against the Chinese. Six million dollars was more than twice the amount the government earned from taxes on tea per annum. The cost in human lives was another figure that the Whig capitalists who controlled Parliament at this time did not care to take into account. Canton was also to be demilitarized, with only a skeletal garrison force remaining in the city. The Chinese would compensate the owners of the looted and demolished factories, and the Spanish were to be reimbursed for the loss of the brig Bilbaino, which the Chinese had burned two years earlier by mistake, thinking it was a British ship carrying opium. In return for these humiliating concessions from the Chinese, the British agreed to leave the Canton River and pull their troops out of all the forts they had occupied. The issues of the opium trade, British possession of Hong Kong, the resumption of trade, compensations for the now mythic twenty thousand chests of confiscated opium, and the exchange of ambassadors were ignored for the sake of securing an end to the hostilities, which the Chinese were clearly losing. The treaty also avoided any mention of a British victory or Chinese defeat to save the Emperor face and encourage his acceptance of the deal.