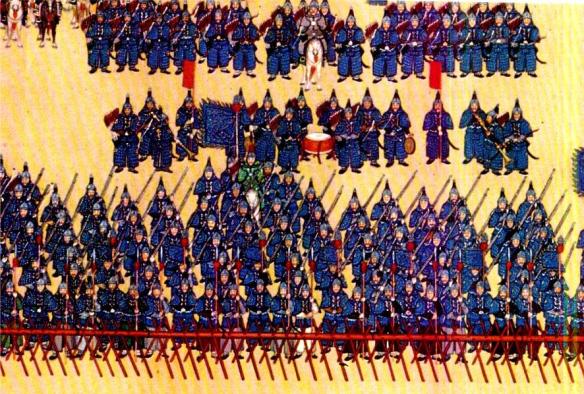

Soldiers of the Blue banner during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.

The Qing dynasty, established by the Manchus, was the last imperial dynasty in China, lasting from the Manchus’ capture of Beijing—the capital of the preceding dynasty, Ming—in 1644 to the founding of the Republic of China in 1912.

The forerunners of the Qing came from the nomadic Jurchen tribes who initially resided in northeastern China, also known as Manchuria, to the north of the Great Wall. In the course of interacting with the Han Chinese, China’s largest ethnic group, the Jurchen tribes gradually transformed themselves into a military and political state, particularly under the leaders Nurhaci (1559–1626), who declared himself the ruler of the Jurchens and the founder of the new Manchu state in 1616, and his son Abahai (1592–1643), who gave the Manchu state a new name, Qing, in 1636.

In 1644 peasant rebels led by Li Zicheng (ca. 1605– 1645) took Beijing. As a result, the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen (r. 1628–1644), committed suicide in Beijing. Seizing the opportunity, Manchu troops moved southward. The Manchus announced possession of the Mandate of Heaven, a concept similar to the European notion of the divine right of kings, after defeating Li Zicheng in 1644.

As a minority numbering roughly two million, the Manchus ruled the 100 million Han Chinese. They owed their first 150 years of success mainly to the first four able emperors: Xunzhi (r. 1644–1661), Kangxi (r. 1661– 1722), Yongzheng (r. 1678–1735), and Qianlong (r. 1736–1996). While making efforts to preserve their own ethnicity, these Manchu leaders adopted the Chinese way: they hired Han Chinese in 90 percent of government posts; waged expansive military campaigns to subjugate rebellious generals in the frontier provinces of Yunnan, Guangdong, and Fujian; consolidated power in Tibet; and incorporated Taiwan and Xinjiang into the China zone.

The late fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries saw the beginning of western European exploration of the world’s oceans and the establishment of trading posts and empires in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, first led by Portugal and Spain, followed by England, the Netherlands, France, and the United States. With regard to China, in 1557 the Portuguese reached a settlement on a lease in the Chinese port of Macao with the Ming regime (1368–1644), and this enabled them to penetrate China’s import–export trade.

In 1600 the English East India Company, a jointstock enterprise, was given a royal charter and became dominant in later Sino–foreign trade centered in the Guangzhou (Canton) area. In 1636 to 1637 British merchant ships arrived at the Pearl River in South China. In 1685 Emperor Kangxi lifted bans, first introduced by the Ming dynasty, on foreign trade. Four years later, the English East India Company entered Guangzhou. In 1757 Emperor Qianlong confined all foreign trade to the city of Guangzhou. On the Chinese side, Sino–foreign trade was administered through Chinese merchant agents, whose organization was licensed and known as the Cohong (guild). The Cohong was first instituted in 1720, then abolished and reinstituted in the following decades.

The main frictions in Sino–British relations occurred because of the imbalance of trade in which China had a range of goods—such as tea, silk, and porcelain—that were attractive to Britain, whereas British merchants could not find any British manufactured products that could sell well in the China market. In 1773 the English East India Company was granted a monopoly over the opium trade in Bengal, and marketed the illegal drug in China. In 1793, received by Emperor Qianlong, British emissary Sir George Macartney (1737–1806) requested greater freedom of trade and the establishment of diplomatic relations, but was rejected because Qianlong did not feel the need for foreign goods.

In 1833 the breakup of the English East India Company trade monopoly by the British government and the lowering of the opium price vastly increased the Chinese demand for opium. A significant number of Chinese became addicted, prompting Qing Emperor Daoguang (r. 1821–1850) to halt opium smuggling. British merchants and the British government responded by attacking Guangzhou and starting the Opium War with China in 1840.

Unprepared to deal with unprecedented military threats from the sea, the Qing lost the Opium War and was forced to accept the Treaty of Nanjing on August 29, 1842. The treaty, along with its supplementary pact, temporarily satisfied British needs: four more Chinese ports—Fuzhou, Ningbo, Shanghai, and Xiamen—were opened to trade; the tariff rate was regulated; the island of Hong Kong was ceded to Britain; and foreign immunity from Chinese law was granted. The Treaty of Nanjing— the first of the ‘‘Unequal Treaties’’—inaugurated the ‘‘Treaty Century’’ (1842–1943) in China, during which the legal, diplomatic, political, economic, religious, and military aspects of Sino–foreign encounters were regulated in various treaties signed between China and foreign powers.

China fought the Second Opium War with France and Britain from 1856 to 1860. The war ended with China’s defeat. In consequence, China had to sign the Treaty of Tianjin of 1858 and the Convention of Beijing of 1860, which specified foreign diplomatic residence and representation in Beijing, as well as the formation of the Zongli Yamen (Office of General Management) to handle foreign affairs.

The Qing regime was further weakened by a series of internal rebellions, the most damaging being the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864). The Taiping Rebellion broke out in the Guangxi Province under the leadership of Christian-influenced Hong Xiuquan (1813–1864). At their height, the Taipings controlled most of South China and founded their capital in the important city Nanjing on the Yangzi River.

In the 1860s some high-ranking court officials came to realize the importance of modernizing China’s military forces by initiating the self-strengthening movement. In the following decades the Qing suffered further defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), which prodded some open-minded Chinese reformers, including Kang Youwei (1858–1927) and Liang Qichao (1873–1929), to persuade Emperor Guangxü (r. 1875–1908) to launch the short-lived ‘‘One Hundred Days Reform’’ in 1898.

In 1899, the antiforeign Boxer Uprising erupted in the Shangdong Province, and the Boxers, under tacit encouragement from the Qing court, rapidly moved up north to Beijing, attacking foreigners and besieging foreign quarters. Joint international forces quelled the Boxer Uprising and punished the Qing authority with the Boxer Protocol of 1901, in which the Qing was forced to pay large sums of indemnities.

The Manchu’s domestic and external failures since the early nineteenth century culminated in a final blow set off by the Wuchang Uprising of October 10, 1911. On January 1, 1912, the Republic of China was proclaimed. One month later, Puyi (1906–1967), the last emperor of the Qing, abdicated, putting an end to imperial rule in China.

The study of Qing history in North America has developed further since 1980. In the early 1980s, Paul A. Cohen suggested going beyond the impact–response paradigm (i.e., the West exerted influence upon an inert China, and China responded passively), which had been laid out by Sinologists represented by John K. Fairbank. Cohen’s China-centered approach aimed at a better understanding of the inner dynamics of development during the Qing period. Since the 1990s topics including civil society, the public sphere, marginalized social forces, globalization, and nationalism have prompted further debates about late imperial China and its relevance to contemporary Chinese modernization and democratization.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Cohen, Paul A. Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984. Fairbank, John King, and Merle Goldman. China: A New History, enl. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999. Gamer, Robert E, ed. Understanding Contemporary China, 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2003. Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China, 2nd ed. New York: Norton, 1999.