One crew of 61 Squadron, led by Flight Lieutenant Burgess, a Canadian, were on their thirteenth trip, of which eleven had been successful and two aborted – both because of engine problems. Although John McQuillan, the rear gunner, had gone through the usual ritual of relieving himself against one of the aircraft’s wheels, he found that soon after they had crossed the enemy coast he needed to go again. It was impossible, however, just to leave his turret at such a time to use the Elsan. He asked the pilot how long before he could do so with reasonable safety and was told, four to five hours, the rest of the crew finding his predicament somewhat amusing! An hour later he was feeling very uncomfortable but trying his hardest not to think about it. By the time they had bombed he was in agony. He saw aircraft going down in flames and wondered who was suffering most, them or him!! After leaving the target he again asked, ‘How long now, Frank?’ and was told about two hours by Frank Burgess. ‘I cannot wait that long,‘ stated McQuillan. With all the fighters and flak about he managed to, or perhaps his mind was taken off his problem, although the rest of the crew were smiling and thinking it a bit of a joke. Eventually nature could not be ignored. It was impossible for him to stand up in the turret so he had to relieve himself where he sat.

On their return they were diverted to Metheringham where they landed at 2.30 am. He was, to say the least, uncomfortable after his experience and his presence in the sergeants’ mess at Metheringham was not a popular one! McQuillan was later shot down in February 1945, but still the agony he suffered that night was never surpassed by anything before or since.

Flight Sergeant Pydden, from Dover, was on his thirteenth trip of his second tour. He got through to the target successfully, and as it was his seventh op to Berlin, he found it the easiest. There was no heavy flak and very little light stuff coming up. They saw little until they were about 60-70 miles into the homeward trip, when a big flash lit up the night sky behind them, which they thought must be an oil or fuel dump going up. Their route took them just south of Magdeburg, then between Hannover and Osnabrück, crossing the Dutch coast south of Den Helder. No route markers were seen, but they made it home safely.

Flying Officer Wimberley, flying Halifax LW510, had taken off at 6.59. A fix on him was made at 10.45 and later a message was received, ‘Aircraft returning to base – one engine U/S,’ followed by another fix at 10.55 when the Halifax was given permission to land at Cranfield. It crashed one mile ahead of the runway and all the crew were killed.

Pilot Officer K.S. Simpson, flying Halifax LW718 ‘T’, had his WOP send a message when they were over the Dutch coast at 10.40. It stated that one engine on the port and one on the starboard side had failed. He then apparently carried on across the North Sea on two engines, crashing at the water’s edge at Ingham, near Cromer, Norfolk at 11.11 pm, ploughing into a minefield where it blew up. All the crew were killed.

Flight Sergeant Brownings in a 103 Squadron Lancaster (ND572 ‘M’) took off at 9.30. When over the Danish coast the rear gunner, Bob Thomas, spotted a Ju88 but Brownings managed to shake it off and went on to bomb the target successfully. As they cleared the target they saw a fighter coned by its own searchlights and with flak all around it. It promptly fired off a red and white star Very flare and the searchlights went off and the flak stopped. Some while later a voice from the rear turret yelled for Brownings to corkscrew as a FW190 was coming in for the attack. This time Fred Brownings could not shake it off and they were raked from stem to stern, and believed they were only saved because the fighter ran out of ammunition. Their intercom was put out of action so Brownings had no idea of any damage or injuries to his crew.

It was left to Jack Spark to go back with a clip-on oxygen bottle and find out. He found it very cold and draughty down the fuselage, but the mid-upper, Sergeant Ken Smart was all right though his foot rest had been shot away, and the hydraulics that powered his turret had been shot out. Right down the tail, he found a very different story. Bob Thomas had taken a direct hit in the attack and was dead in his turret.

To add to their problems there was a five-foot gap in the top of the port wing and one of the tanks was open to the elements and the flaps damaged beyond repair. Brownings was having to use his legs to control the column to prevent the aircraft from stalling. The crew were told to strap on their parachutes but Jack Spark found his in shreds, having been hit by a cannon shell. They were then coned by searchlights so Jack, remembering the fighter’s flare shot, fired off the only ones they had, three reds and three white stars. It worked, and the searchlights went straight out and the firing ceased.

With only about twenty minutes of fuel left they came down on Dunsfold airfield but all the lights were out as German intruders had been over the south of England that night. Without any air to ground radio, which had also been hit, they fired a red Very cartridge at intervals and eventually the lights came on and they came into land. His first attempt was too high so he went round again. On his second attempt he managed to get down but then they slewed off the runway and hit something, which brought them to an abrupt halt. They had hit an American B17 Flying Fortress named ‘Passionate Witch’ that had crashed two days earlier.

The body of the rear gunner was extricated from his turret; all the rest of the crew were uninjured apart from shock, to the extent that they could not sleep. In July, four of the crew were decorated. Fred Brownings was commissioned and together with Norman Barker and Arthur Richardson received the DFC, Jack Spark the DFM. Strangely, their trip to Berlin was not mentioned in their citations.

Pilot Officer Davies, flying Lancaster LW587 ‘V’, was airborne when the WOP, Flight Sergeant Woodward, discovered he had left his parachute harness behind, so they jettisoned the bombs into the sea and returned to base. One wonders what sort of reception he got back at base.

Many aircraft landed at Coltishall, a fighter station, having been diverted from their own bases due to weather. The quantities of surplus petrol in tanks on landing makes interesting reading. No 1 Bomber Group recorded that only nine of its aircraft returned with less than 100 gallons, but it is unlikely that petrol shortage through the strong wind, contributed to any losses.

The German European Service in English, broadcast at 10.30 pm on 25th March announced:

The general impression in Berlin after last night’s raid was that the raid had been one of the lightest sort. Berliners on their way to work this morning, looked in vain for the bomb craters. It was not until military HQ issued the first reports that it was realised that a big raid had been planned, and had been frustrated by the German night fighters.

A continuation of the report was made on the 26th when an air raid warden at one of the big Berlin bunkers described his experiences of the raid:

I realised at once that something out of the ordinary was happening, for in previous raids I’ve always been able to notice the arrival over the City of the different waves of enemy bombers, but this time they came over all at six’s and seven’s, like an armada that had been scattered by the storm.

The German Telegraphic Service at 1.32 am on the 26th, reported:

English bombers again made a large scale attack on Berlin in the evening hours of Friday. The raid has definitely the character of a terror raid. The raiders dropped a large number of HEs and IBs on all parts of the city. German ack-ack batteries and night fighters attacked the raiders. How many enemy planes were shot down is not yet known as only incomplete reports are yet to hand.

A further report at 2.16 am recorded:

British formations approached the Reich and were intercepted between 9.00 and 10.00 on the evening of the 24th of March by strong German night fighter formations. The first of a series of aircraft shot down was between Freiberg and Kiel. Four streams of enemy bombers reached the Reich capital from the north west for more than an hour without pause. According to reports so far available, very heavy RAF losses may be expected. The attack was again aimed at Berlin, bombs were dropped at random in moderate visibility all over the built up area of the city – the terror nature of this attack is obvious. Many four-engined bombers were shot down over Berlin itself and the south-west suburbs. The enemy aircraft continued to be attacked as they flew off. In the west, small formations bombed the Leipzig and Weimar areas. 2,240 tons of bombs were dropped.

When the crews had been debriefed and gone finally to their beds to try and sleep for what was left of the night, many could still feel and hear the throb of their engines. Often the RAF police would come into a billet and collect the kit of the crew who had not returned.

The next day only the memory of them remained.

On this night, when the last heavy bomber raid on Berlin by the RAF was made, another historic situation was developing not far away. Today it is known as ‘The Great Escape’, when 76 RAF and Allied airmen escaped from Stalag Luft III at Sagan. Of these 76, three reached safety. Of the others who were recaptured, 50 were murdered by the Gestapo.

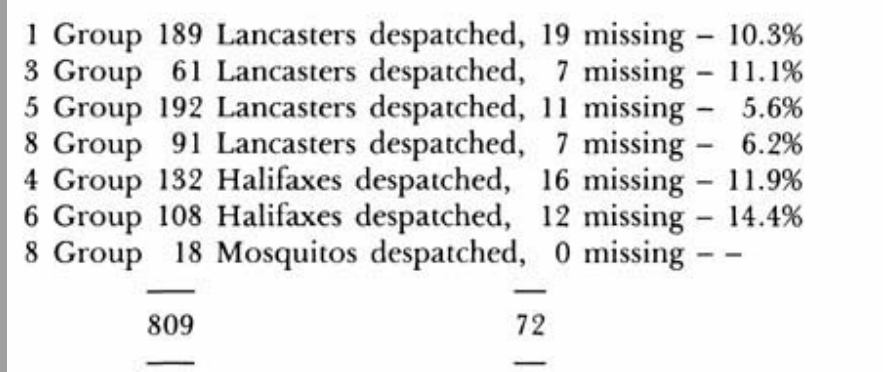

The RAF Losses On this night were 72 aircraft, which was a loss ratio of 8.9%. Broken down it showed that out of the force of 809 bombers the Group’s totals were:

Of the force, 43 returned early. Of the 72 lost, 45 were estimated to have fallen to flak, 18 to night fighters, the other 9 unknown. Statistics shown another way record:

The Pathfinders marked between 10.25 and 10.27 pm

The first wave bombed between 10.30 and 10.33 pm

The second wave bombed between 10.32 and 10.36 pm

The third wave bombed between 10.36 and 10.30 pm

The fourth wave bombed between 10.39 and 10.42 pm

The fifth wave bombed between 10.42 and 10.45 pm

There were 26 ABC aircraft from 1 Group but all returned safely. The losses to flak were, seventeen on the outward journey, seven in the target area and 21 on the way home. To fighters, six on the outward, four over the target, eight on the homeward run. The German Fighter Corps IJ claimed 80 aircraft shot down and reported losing one fighter themselves. Goebbels Overseas News Agency claimed 110 aircraft destroyed.

The German AA Batteries at this time were using 128 mm guns with much higher and greater radius of bursts, concentrated in Grossen Batterien, huge groups of up to 40 guns that worked in rectangular patterns known as box barrages. This night resulted in the best score for German flak guns in the war thus far.

Undoubtedly the major factor in the night’s saga had been the wind. On the 25th March, the Meteorological Section of Bomber Command HQ was visited by the Director of the Met Office of the Air Ministry, Doctor Petterssen, to discuss the difficulties in forecasting winds from available data over enemy territory. It was agreed, particularly in the light of winds forecast, and the actual winds found on the night of the 24th/25th, that more upper air data from Sweden would be of assistance on these occasions. An analysis of navigation for this Berlin raid was undertaken to discover reasons for the wide scatter of the force and its displacements to the south of the ordered track. The southerly displacement obviously resulted from a systematic error in the broadcast winds, both past and forecast, the strength being in all cases too low. This under-estimate of the strength was due in about equal proportions to:

- Lack of belief in the unusual wind strength on the part of the many wind finders.

- The time delay between the transmissions, by wind finders,and their reception at Bomber Command HQ.

The wind finders transmitted less than half the winds that they found, 40% used the recommended period from 15 to 30 minutes for wind determination. The main reason for the scatter was that only about 55% of the winds used by navigators was the correct broadcast winds. Very simply this meant that the wind finders just could not believe the winds speeds they were reading and reduced them by anything from 5 to 15 mph. In turn, the Met boys in England could not believe even these reduced figures. So winds of 115 mph were reduced to around 110 by the wind finders and down to around 95 mph by the Met people at Bomber Command. The estimated true winds coming from the north and the use of the slower wind estimations when calculated to courses to fly, caused the aircraft to drift more and more to the south off track and into the flak defences of towns they should have not flown near – hence the heavy losses. It really was a case of a war with the elements – and the elements won.