The warrior women of Dahomey, an ancient kingdom in West Africa and present-day Benin, first came to the attention of European travelers in the latter half of the sixteenth century. A German book published in 1598, Vera Descriptio Regni Africani, describes an African royal court whose palace guard consisted of women, and similar royal formations occurred elsewhere in the world from ancient times, particularly in the East. The kings of ancient Persia had female bodyguards, as did a prince of Java.

As late as the nineteenth century, the king of Siam, now Thailand, was guarded by a battalion of four hundred women armed with spears. They were said to perform drills better than male soldiers and were crack spear-throwers. Women in general were regarded as more loyal and trustworthy bodyguards than men, because they were less likely to be bribed or suborned; many rulers chose female bodyguards for this reason.

But the women of Dahomey outclassed them all. More than 250 years after the first reference, we catch sight of them again in the high summer of the British Empire when the British general Sir Garnet Wolseley, in a report on his successful campaign against the Ashanti (1873–74), compared his energetic and disciplined Fanti female porters to the king of Dahomey’s “corps of Amazons.”

Eighteenth-century accounts of Dahomey by European merchants and slave traders—slavery was the basis of the kingdom’s wealth—paint a picture of a colorful feudal world whose kings were surrounded by hundreds of serving girls and guarded by armed women. One of Dahomey’s kings, Bossa Ahadee, would march in ceremonial procession accompanied by several hundred wives, surrounded by female messengers and slaves, and escorted by a guard of 120 men armed with blunderbusses and 90 armed women.

The presence of the armed women was, at this stage in Dahomey’s history, more a symbol than a real threat to Dahomey’s neighbors. The tables were turned, however, when one of them, the king of Oyo, took to the field against the Dahomeans with a raiding party of eight hundred women to enforce a claim of female tribute he had leveled against King Adahoonzou. It was left to the all-male Dahomean army to defeat the Oyan Amazons.

By the time of King Ghezo (1818–58), Dahomey’s royal court consisted of some eight thousand people, the majority of them women, many of whom existed in a minutely graded pyramid of concubinage, at the top of which were the so-called Wives of the Leopard, the women who bore the ruler’s children. One of the functions of the armed female element of the court, all of whom were recruited in their early teenage years, seems to have been the capture and execution of women from rival tribes. All the “Amazons” carried giant folding razors, with blades over two feet long, which were apparently used to decapitate female enemies and castrate male foes.

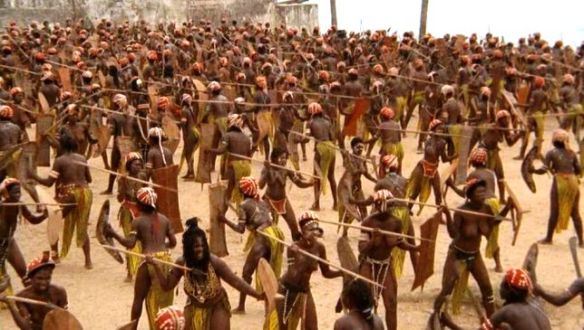

From the late 1830s Ghezo seems to have used members of his predominantly female court in battle against neighboring tribes. It is possible that he deployed four thousand female warriors in an army totaling sixteen thousand. When in 1851 he laid siege to the city of Abeokuta, the siege was repulsed with losses of some three thousand, of whom two thirds were women. A French account of the engagement describes their officers standing in the front line, “recognisable by the riches of their dress” and carrying themselves with “a proud and resolute air.” Nevertheless, these women warriors occupied an inferior and ambivalent position in the hierarchy of the Dahomean court and, significantly, referred to themselves as men in their war cries and battle chants.

Far from discouraging Ghezo, this setback spurred him on to include more women in his army. They seem to have been divided into a regular corps of well-trained and highly disciplined “Amazons” armed with muskets and machete-like swords, who also formed an elite personal bodyguard, and a rather less satisfactory reserve, armed with cutlasses, clubs, and bows and arrows, who were more interested in rum than rigorous military discipline. In peacetime the “Amazon” corps was wholly segregated from men, and outside the confines of the royal palace its approach was signaled by the ringing of bells, upon which civilians had to turn their backs and males had to move away.

There were several practical reasons for Ghezo’s use of women in battle. Dahomey was exceptionally warlike, and lost many men on campaign, while simultaneously depending for its wealth on a slave trade that favored the disposal to slavers of a large proportion of its able-bodied male population. At its peak strength in the early 1860s, the Dahomean army was approximately fifty thousand strong—one-fifth the total population—of which the female element numbered ten thousand, a quarter of their number consisting of the “Amazons.”

It has been suggested that many of the women, as well as some of the men in the Dahomean army, went to war as camp followers, much in the manner of the soldaderas who marched with Mexican armies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Victorian explorer Sir Richard Burton, who saw them in 1863, likewise poured derision on “the fighting Amazons.” “Mostly elderly and all of them hideous,” he ruminated with all the authority of the European white male, “the officers decidedly chosen for the size of their bottoms…they manoeuvre with the precision of a flock of sheep.” But he also noted that this army, then some 2,500 strong, was well armed and effective in battle. Nor could all of them have been old and hideous, since all 2,500 were official wives of the king.

In spite of the dread in which they were held, the “Amazons” were no match for small but well-armed colonial armies. In a series of engagements in 1892, the male and female Dahomean warriors were defeated by a French army, and the kingdom became a colony of France. The victorious French commander commended the women warriors on their speed and boldness and installed a puppet ruler who was permitted a few token women in his bodyguard. A troupe of so-called Amazons from Dahomey formed part of a display at the recently erected Eiffel Tower, under which they danced and drilled.

Reference: Stanley B. Alpern, Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey, 1998.