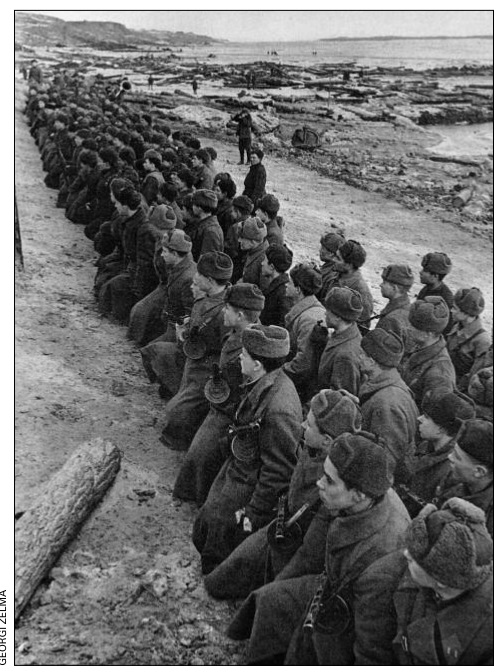

The Red October Steel Works, lying south of the Barrikady, was attacked on October 23 by the newly-inserted 79. Infanterie- Division. In two days of stiff fighting they captured a large part of the plant but were unable to conquer its south-eastern corner, the keystone of which was the formidable Martin Furnace Hall (Hall 4). Defending the factory, along with units of the 193rd Rifle Division, was the 39th Guards Rifle Division. They doggedly held on to the factory for four months, until the final German capitulation. Sometime during the battle, Soviet combat photographer Georgi Zelma took this well-known picture of men of the 39th Division, assembled on the nearby Volga bank, being awarded with the Banner of the Guards.

This colour photograph, taken by a soldier from Infanterie-Regiment 578, Hans Eckle photographs what looks like the two StuGs proceeding further into the Dzerzhinsky factory grounds. The large building in the background housed the factory administration and offices. The regimental attack was supported by assault guns from StuG-Abteilung 245 and part of StuG-Abteilung 244

(November 11-18)

During this period of diminishing activity, Paulus was desperate for fresh forces to resume his attack. On November 1, he conferred with von Weichs and Generaloberst Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, the commander of Luftflotte 4, to discuss how the city could be secured before the weather took a dramatic turn for the worse, something that might be only days away. Having been caught unprepared in 1941, by the end of October winter clothing began to be issued to the 6. Armee yet poor weather would still cripple Paulus’s already overtaxed supply route to the western railheads, and close air support would be practically neutralised.

While Richthofen offered Paulus a portion of the Luftwaffe’s rail capacity in order to quickly stockpile the ammunition needed for the final attack, the 6. Armee’s commander agonised as to how he could reorganise his line to provide von Seydlitz’s LI. Armee – Korps with assault troops that simply did not exist. A request to the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH – German Army High Command) for the bulk of the 29. Infanterie-Division (mot.) was rejected as the OKH would not sanction any further transfer of line divisions into the city. Instead, five assault engineer battalions were scavenged from army troops and various divisions outside the 6. Armee which reached Paulus between November 4-6. In addition, his two StuG battalions in the city would be reinforced with the first 12 units of a new 150mm infantry gun – the StuIG 33B – which was mounted on a heavily armoured PzKpfw III assault chassis. Together, this force was entrusted with delivering the final German victory that would eliminate the last Soviet bridgehead, and render the city secure before the onset of winter. Now Paulus, Seydlitz, and Oberst Herbert Selle, the Armee-Pionier-Führer (Commander of Engineer Troops) of the 6. Armee, began planning the final offensive to be named Operation `Hubertus’.

After precious days of haggling between the German High Command and various generals concerning the offensive’s participants, objectives and timing, a commander was nominated to lead the attack, scheduled to be launched on November 11. Major Josef Linden, himself a pioneer battalion commander and also director of the 6. Armee’s specially created Pionier-Schule (assault engineers training school), began to take stock of his forces and set forth planning the offensive that was estimated to eliminate the last remaining Russian bridgeheads in the city. Across a battlefield littered with shell-holes, bombed buildings, rubble and twisted metal, the pioneers would systematically and methodically implement their craft at destroying one Soviet strong point after another. In their trail, an ad-hoc group of storm companies formed from all the remaining infantry and non-essential service personnel in the city, would provide cover and mop up after the engineers. Despite lastminute protests for proper infantry battalions from the 60. and 29. Infanterie-Divisions (mot.) to cover the pioneers, Seydlitz proceeded with the unenviable task of stitching together his unconventional infantry force by scavenging men from every type of unit in his corps.

The plan itself called for decoy attacks along the entire line, from the XIV. Panzer – Korps near Rynok to the old city defended by the 13th Guards Rifle Division. The main assault would come from seven assault engineer battalions — Pionier-Bataillone 45, 162, 294, 305, 336, 389 and Panzer-Pionier-Bataillon 50 — against the Soviet strong points in the vicinity of the Barrikady factory. They would be supported by infantry of the 305. and 389. Infanterie-Divisions, themselves augmented by battle groups from the two StuG battalions, and company-size contributions from the 14. and 24. Panzer-Division and the 44. Infanterie-Division (General – major Heinrich Deboi).

The major objective of `Hubertus’ would be to seize the Volga shoreline immediately to the east of the Barrikady factory. A somewhat lesser, yet significant attack would also be launched in the vicinity of the Red October plant by the assault engineer unit – Pionier- Bataillon 179 – and troops of the 79. Infanterie-Division, although this was considered of secondary importance. In addition to the Croatian Legion (known to the Germans as verstärktes (kroatisches) Infanterie- Regiment 369), the 79. Division would also be augmented by forces from the 24. Panzer- Division: two panzergrenadier battalions, a motorcycle battalion and its armoured engineer battalion, Panzer-Pionier-Bataillon 40. It is no wonder then that `Hubertus’ would become known as the `Battle of the Pioneers’.

Chuikov, now in his new command post beside the riverbank east of the Lazur Chemical Plant, also considered his situation. His depleted army was holding two bridgeheads but neither one was more than 800 metres deep. The northern pocket was deployed around Spartanovka and the southern one at `Pavlov’s House’ with a thin strip along the riverbank all the way north to the Brickworks. Chuikov had successfully conducted several local counter-attacks, and had steadily taken in replacements for some of his losses which had injected a much-needed morale boost to his army. Correctly anticipating another enemy attack in early November, he had ordered a much-needed reorganisation and consolidation of the battered defenders, and his defence now stood as follows:

To the north (Rynok and Spartanovka area), Colonel Sergei Gorokhov commanded an isolated composite force of 1,000 men from the decimated remains of a few brigades and an NKVD regiment.

Of the main bridgehead ranging from the northern boundary of the Barrikady riverbank through the Red October and Lazur to Pavlov’s House stood seven eroded divisions, a rifle brigade, and a rifle regiment. Furthest north was the 118th Rifle Regiment (the only surviving combat unit of the 37th Guards Rifle Division), which was now under the command of their southern neighbour, Colonel Ivan Lyudnikov and his 138th Rifle Division (also augmented with the survivors of the now defunct 308th Rifle Division and defending the Barrikady area). On their left flank were the reinforced 95th Rifle Division, 45th Rifle Division, 39th Guards Rifle Division (reinforced) and 92nd Rifle Brigade (reinforced) covering the area of the Red October through the Lazur Chemical Plant and Tennis Racket, the 284th Rifle Division on the base of the Mamayev Kurgan, and the 13th Guards Rifle Division occupying the northern part of the old city. In reserve, the 193rd Rifle Division was held back to defend the supply ferry.

At 0340 hours on the freezing morning of November 11, a heavy barrage announced the opening of the Germans’ final assault. Not only was the main attack supported by artillery, but Paulus had every division along the entire front in the city, from north to south, initiate deception attacks to help pin down Soviet forces and prevent Chuikov from reinforcing the Barrikady area. This heavy barrage was quickly matched with Soviet counter-fire. In the face of this intense shelling, the infantry of both sides could only hug the earth as tightly as possible and stay motionless until the barrage had relented. Selle’s assault engineers now began their methodical and slow advance against the Soviet defences, being supported at 0630 by a lightning Stuka attack on the Soviet forward artillery observation posts. One by one, Soviet strong points were reduced by small groups of German sub-machine gunners, flame-throwers and teams with satchel charges.

Chuikov immediately counter-attacked by thrusting Gorokhov’s infantry towards the Tractor Factory, but by noon his Volga bridgehead was split again as the assault engineers reached to within 600 metres of the river just south of the Barrikady factory, cutting off Lyudnikov and his defenders in a pocket measuring just 400 by 700 metres.

By evening Lyudnikov was running low on supplies and ammunition and the Pharmacy had fallen, yet at the same time casualties for the Germans had been severe, both in the Barrikady area and Red October, the latter attack having been a complete failure. As predicted, the heavily-laden assault engineers were quick to run out of ammunition, and often found themselves unsupported by the ad-hoc infantry teams to their rear. They had taken 30 per cent casualties, and were still expected by high command to take the Martin Furnace Hall in coming days if the efforts of the 79. Infanterie-Division proved fruitless.

Now constantly under fire from Soviet artillery, the exhausted German attack was suspended on the 12th to be resumed the following day. A few more buildings, including the formidable `Commissar’s House’ were taken, but the Germans had to rest yet again the following day, limiting themselves to clearing one house at a time. Generals in command of hundreds of thousands of men spread out over many square kilometres were now reduced to issuing orders to battalions and companies the size of platoons, directing which house to take that day. Seydlitz attacked again east of the Barrikady on the 15th but achieved only modest gains and failed to eliminate the Lyudnikov pocket.

A spoiling attack by Chuikov during the evening persuaded Seydlitz to suspend his offensive for the following day. During the 17th and 18th, the final German assault in the city resulted in only modest gains in the Spartanovka area. By this time, further attacks against the factories had become an exercise in futility, and the window for victory had at last closed for Paulus. Now, Rumanian observation posts were sending through reports of masses of Soviet tanks warming up their engines behind the front line.