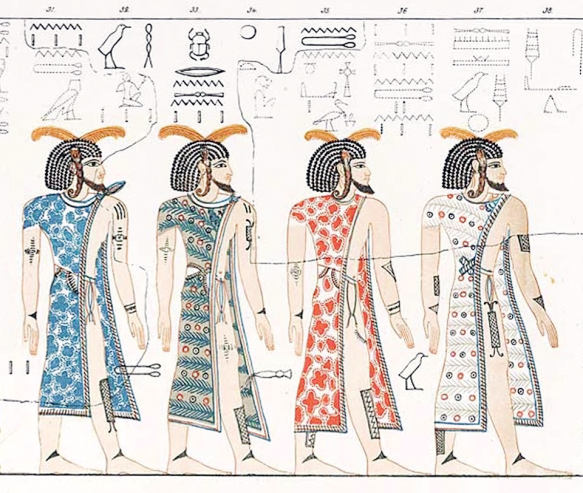

“Libyans” were one of the traditional enemies of Egypt and appear to have been almost any desert-dwelling, nomadic or seminomadic population, which lived to the west of the Nile valley. Conflict between Egypt and Libyans is suggested (if not fully attested) by the “Libya Palette,” the reliefs in the pyramid temple of Sahure, and of Menthuhotep II at Deir el-Bahari. The archaic names Tjemeh and Tjehenu are used throughout the dynastic period, but, from the 19th Dynasty onward, specific tribal groups are named: the Seped, the Libu, and the Meshwesh. These groups became a grave threat to Egypt. Sety I included scenes of his Libyan Wars in the cycle of his campaigns depicted at Karnak (Thebes). A string of fortresses to control Libyan movements toward Egypt was built in the reign of Ramesses II. Stretching westward from Memphis along the western edge of the Delta to Rakote and on through Karm Abu-Girg, el- Gharbaniyat, and Alamein to Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, the forts seem to have lasted only for this reign. Perhaps forced by famine to find new grazing lands, Libyan groups invaded Egypt in the reign of Merenptah and Ramesses III.

Ramesses III settled Libyan soldiers in garrison towns, probably around Bubastis. The text of a stela from Deir el-Medina also refers to the victories of these years and suggests that Ramesses might have forced assimilation.

Later in the 20th Dynasty, there were Libyan incursions into Upper Egypt particularly around Thebes. A statue of Ramesses VI shows him leading a Libyan captive. The Libyans dominated Egypt during the Third Intermediate Period, with the dynasty founded by Sheshonq I. The Libyan dynasts of the Delta presented a major source of opposition to the attempts of the kings of Kush and Assyria to control Egypt. Psamtik I, probably a descendant of Libyan dynasts, led campaigns against the “Libyans” early in his reign. Later references are more specific about locations.

The principal weapon of the Libyans was the bow. Only one Libyan in the battle reliefs of Sety I carries a sword (of non-Egyptian type), but the battle reliefs of Ramesses III show other weapons and chariots. These weapons were clearly the result of the arms trade and are probably to be associated with the presence of small groups of the Sea Peoples, probably mercenary soldiers, who fought alongside the Libyans.

LIBYAN WAR OF MERENPTAH (year 5 c. 1208/1207 BC).

The principal records are the text of the Israel Stela from the pharaoh’s temple on the west bank at Thebes, the stela from Karnak with a duplicate text, and the record on the east wall of the Cour de la Cachette between the main temple and the Seventh Pylon. The Libyans were dominated by the Libu, led by Mariyu, son of Didi. They had penetrated Egypt, along the western fringe of the Delta and a battle, lasting six hours, was fought. The invasion was apparently meant to have been synchronized with a rebellion in Nubia and was allied with groups of the Sea Peoples. The casualties of the specified groups are relatively small, compared with Libyan casualties of 6,359: Ekwesh (2,201), Teresh (742), Shekelesh (222), Lukka and Sherden (200?). This suggests that the Sea Peoples are, in this case, mercenary troops. The Libyan movement is specifically stated to have been caused by famine in Libya.

LIBYAN WAR OF SETY I.

Although conflict with Libyans is documented from earliest times, the major Libyan Wars occurred in 19th Dynasty. The first to be recorded by prominent battle scenes is that of Sety I, forming part of the cycle of reliefs on the north outer wall of the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak (Thebes). There are four scenes. The first shows Sety in his chariot, his forward foot on the chariot pole, the reins tied around his waist, charging and about to kill the large figure of a Libyan chief. Sety wears the khepresh and grasps his strung bow, wielding the khepesh-sword for close combat. The chief, possibly of the Meshwesh, wears the feather and phallus sheath. The royal chariot charges into the melee of wounded soldiers who carry bows, only one has a sharp sword. In the second scene, the pharaoh has descended from his chariot and, trampling over fallen Libyans, grasps the chief and is about to kill him with a short stabbing spear. Sety wears the lappeted wig. The third scene shows the triumphant return. The pharaoh, wearing the khepresh, drives his chariot, holding the reins along with his bow, khepesh, and whip. The chariot is decorated with the heads of Libyans. Before him, the pharaoh drives two lines of captives, their arms tied at the elbows. The final scene shows the presentation of captives to the Theban gods, along with booty of elaborate vessels and two tusk rhyta, all of typically Asiatic type. The texts use only the generalized term Tehenu and are otherwise uninformative about locale and enemy. The pharaoh is likened to Monthu and Horus and is described as “like Baal when he treads the mountains.”

LIBYAN WARS OF RAMESSES III (year 5 c. 1180 BC; year 11 c. 1174 BC).

The Libyan Wars of Ramesses III are recorded by reliefs on the north exterior wall and in the first courtyard of the pharaoh’s temple at Medinet Habu on the west bank at Thebes. The first invasion was an alliance of the Meshwesh, the Libu, and the Seped. The scenes show the pharaoh setting out, with heralds and musicians (trumpeters), and, in its own chariot, the standard of Amun. The Egyptian army includes Egyptians with khepesh and shields; Nubians with throw sticks (or cudgels), spear and axe; Nubian archers; mercenaries from Asia and the Sea Peoples (mixed contingents of Shardana and Peleset). The battle scene includes the typical melée and a fortress called “the town of Ramesses who has repulsed the Temeh.” The aftermath includes the military bureaucracy counting the severed hands and phalluses of the enemy. In one scene, the pile of genitals shows penis and testicles, rather than the phallus alone.

The second Libyan War of year 11 (c. 1174 BC) was led by Meshesher, chief of the Meshwesh. The scenes show the battle, in the western Delta, in which the Libyans use chariots and foreign weapons. The chariots, notably, have wheels with four spokes. The Libyans were defeated and routed. Pursued by the Egyptian army, they fled past two fortresses, one called the “Castle in the Sand.” The inscriptions state that, in this pursuit, 2,275 Libyans were killed. The scenes of the presentation of captures to Ramesses III include the severed hands and phalluses, captives, and a large array of weaponry, including long, sharp swords of Asiatic type.