The Battle of Crysler’s Farm

(May 4, 1783–February 15, 1826)

English Army Officer

Morrison won the hard-fought Battle of Crysler’s Farm in 1813 against an American force three times his size. His victory single-handedly turned aside a major attack upon Montreal and was the most dramatic display of British military prowess during the War of 1812.

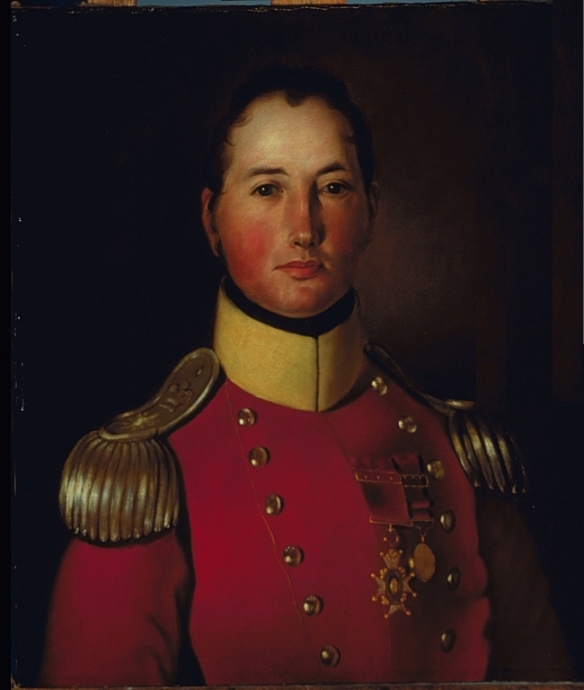

Joseph Wanton Morrison was born in New York City on May 4, 1783, a son of John Morrison, then deputy commissary general in North America. Following the American Revolution, Morrison relocated back to England with his family, and he was commissioned an ensign in the British army in 1793. After several years on half-pay with an independent company, he joined the 17th Regiment of Foot in 1799 and first experienced combat at Egmond aan Zee, Netherlands. The following year he reported to Minorca for garrison duty, remaining there until 1802. Two years later he was stationed in Ireland as an inspecting officer of yeomanry (volunteer militia), and in 1805 he joined the unit most closely associated with his career, the 89th Regiment. This was an Irish-recruited regiment, distinct in red jackets and black facings (collars and cuffs). After several more years of garrison duty, Morrison transferred with his regiment to Halifax in October 1812. The War of 1812 against the United States was then in full swing, and he marched his battalion to Kingston, Upper Canada (Ontario), as part of the garrison. An excellent drillmaster, he spent several months constantly inspecting his troops, training them, and in every way honing the 89th to a fine tactical edge. Curiously, the 30- year-old Morrison had never personally commanded a battle by himself despite fifteen years of active service.

The fall of 1813 gave rise to an ambitious American strategy for the conquest of Canada, conceived by Secretary of War John Armstrong, which involved two distinct strategic thrusts from the west and south. The first column was under Gen. James Wilkinson, who commanded up to 8,000 soldiers at Sackets Harbor, New York. His objective was to pile his army onto a vast armada of boats and conduct an amphibious foray down the St. Lawrence River. Meanwhile, a force of 4,000 men under Gen. Wade Hampton would concurrently advance from Plattsburgh, New York, up the Champlain Valley and into Lower Canada. There the two columns would unite in anticipation of a rapid conquest of Montreal. Capture of that strategic city would all but ensure the fall of Upper Canada and points west. It was the largest American offensive conducted thus far in the war, but sheer numbers belied its overall inadequacy. First off, the campaign commenced too late in the fall to have any prospects of success, for the moment winter weather arrived operations would have to cease. Second, the choice of generals to lead this critical conquest was poor, as Hampton and Wilkinson were bitter personal enemies who refused to cooperate-or even correspond- in reasonable fashion. The third major factor militating against American success was the state of the U. S. Army. The majority of regiments involved had been only recently recruited, and soldiers and officers alike remained poorly trained. Aside from skirmishing and marksmanship, which had been American tactical specialties since revolutionary times, the U. S. Army was singularly unprepared to confront well-led, highly disciplined British regular forces in the field.

In late October 1813, as Wilkinson’s armada sailed passed the Kingston garrison, Gen. Francis de Rottenburg ordered Morrison to take a corps of observation totaling roughly 1,000 regular troops, militia, and Indians and shadow American movements downstream. Morrison complied and, assisted by a British gunboat flotilla, dogged Wilkinson’s heels for several days. That general grew concerned over the presence of so many British troops operating at his rear, so on November 11, 1813, he ordered the army landed and arrayed against its pursuers. Morrison, who had also come ashore, deployed on Crysler’s Farm, an open area astride the St. Lawrence. His right flank was secured by the river and gunboat squadron, and his left anchored upon a deep woods. Thus, the Americans had no recourse but to attack head-on, over land that was deeply rutted by ravines and difficult to traverse. Morrison commanded his own 89th Regiment, a battalion of the famous 49th Foot (the Green Tigers), three companies of French-speaking chasseurs (light infantry), and about 250 Mohawk warriors. He was also ably seconded by his staff officer, Lt. Col. John Harvey, one of the heroes of Stoney Creek four months earlier.

The ensuing Battle of Crysler’s Farm constitutes a unique tactical microcosm of the War of 1812, for no encounter more clearly highlights the profound tactical disparities that separated the British and American armies. With Wilkinson being sick, command devolved upon Gen. John P. Boyd, a former mercenary. He deployed three brigades of infantry and one squadron of cavalry, in excess of 3,000 men at his disposal. This was three times the manpower that Morrison possessed, and the American strategy was simply to overwhelm the enemy by sheer numbers. Boyd then made the mistake of committing his brigades piecemeal along different portions of the field. This allowed the British commander to expertly change the facing of his units under fire, confront the stumbling Americans, and blast them back with accurate musketry. In sum, Boyd had been lured into a set-piece battle against highly trained professional soldiers, fighting upon ground of their own choosing. The result was a disaster.

For several hours the Americans fought bravely, but ineptly, and could not drive back the British. The red-coated regulars were exceptionally well drilled and inflicted punishing blows upon their assailants. Once Gen. Leonard Covington had been fatally wounded and his brigade disrupted, Morrison judged the timing ripe and ordered an advance across the field. Boyd’s entire army then bolted from the field in confusion, and only a determined charge by the Second Light Dragoons temporarily delayed the surging tide of bayonets. Within 30 minutes, the American force had reembarked upon its boats and was paddling downstream to safety. The thin red line had never been stretched thinner or proved more resilient. British losses were heavy, amounting to 200 killed and wounded, but Boyd lost twice as many casualties, including 100 prisoners. It had been a stirring performance by Morrison in his first independent action-a stinging tactical reversal for the United States!

As a consequence of Crysler’s Farm, Wilkinson and his subordinates decided to abandon their offensive and enter winter quarters. This coincided with Hampton’s decision to do the same, following his embarrassing defeat at the hands of Charles-Michael d’Irumberry de Salaberry at Chateauguay three weeks earlier. Morrison was awarded a gold medal, was voted the thanks of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada, and then proceeded back to Kingston. He remained in garrison until late July 1814 and subsequently accompanied Gen. Gordon Drummond to the Niagara frontier. On July 25, 1814, the 89th Regiment was one of the units rushed into action during initial phases of the Battle of Lundy’s Lane and inflicted heavy losses upon Gen. Winfield Scott’s brigade. However, Morrison was struck down by a bullet early on, and his regiment lost nearly a third of its numbers in combat. After a long convalescence, he saw no further service and returned to England in 1815 with his surviving soldiers.

Back home, Morrison rose to brevet colonel of the 44th Regiment in 1821 and resumed full-time activity. The following year he was shipped off to India and stationed at Calcutta, where he gained an appointment as a local brigadier general and was ordered to mount an expedition to Arakan against Burmese forces gathered there. This campaign was successfully concluded, but the hot climate riddled the British soldiers with disease, and Morrison fell ill among them. Shipped home in an attempt to improve his health, he died at sea on February 15, 1826. Morrison, unquestionably, was the most accomplished regimental-grade British officer of the War of 1812.

Bibliography Chartrand, Rene. Canadian Military Heritage. 2 vols. Montreal: Art Global, 1994-2000; Elting, John R. Amateurs to Arms! A Military History of the War of 1812. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991; Graves, Donald E. Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm. Toronto: Robin Brass Studios, 1999; Patterson, William. “A Forgotten Hero of a Forgotten War.” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 78 (1990): 7-21; Stanley, George F. G. The War of 1812: Land Operations. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1983; Suthren, Victor J. H. The War of 1812. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1999; Way, Donald. “The Day of Crysler’s Farm.” Canadian Geographic Journal 62 (1961): 184-217.