Santa Anna heats up the conflict

A big shift in the Mexican political scene spelled even more trouble for the Texans. In 1834, the celebrated war hero Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna (1794-1876) became president of Mexico. The conservative Santa Anna immediately put into place a centralist government that took power away from the individual Mexican states. Regarding the troublesome Texas colony, Santa Anna was adamant: no nonsense would be allowed! In 1835, Santa Anna made a major show of force by sending troops under General Martin Perfecto de Cos (1800-1854) to forts all along the Rio Grande, a river south of the Nueces River, which formed the border of the Texas colony. The borders were heavily patrolled, and troops kept up a very visible presence in Texas towns.

Instead of intimidating the Texans, however, this action just made them more angry. Settlers began firing on Mexican troops, who returned fire. Soon the Texans had formed an armed resistance group, or militia, that was small in number but big in spirit. In early October 1835, this militia took control of the towns of Gonzales and Goliad, and by the end of the month they had arrived at the fortified town of San Antonio, where there were 400 troops stationed under the command of Cos. The Texans, including about 100 from the original militia plus about 300 new volunteers, spent the next six weeks trading shots with the Mexicans, mounting a major seize on the fort in early December. On December 10, having lost 150 of his soldiers, while the Texans lost only 28, Cos surrendered San Antonio. He and his troops were stripped of their weapons but, after they promised not to fight the Texans again, they were allowed to march back into Mexico.

About a month earlier, the U. S. settlers had sent Austin to the United States to try to drum up some support for the Texan rebellion. U. S. president Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) sympathized with the Texans, but he did not feel he could offer more than moral support. Already there had been talk of statehood for Texas, but such a development would surely upset the delicate balance of states in which slavery was either legal or illegal. For now, the U. S. government could send no money or troops to help the Texans, but that restraint did not apply to individual U. S. citizens. Inspired by what they saw as a freedom struggle, and often hoping they would be rewarded with free land when the conflict was over, many people, especially those from border states like Georgia and Louisiana, began volunteering to help fight the Mexicans, while others sent guns, supplies, and money to Texas.

Santa Anna received the news of the Texans’ rebellion with fury. In early 1836, convinced that he must teach the U. S. settlers a lesson-and also send a warning to the U. S. government, which he believed was involved-Santa Anna sent six thousand experienced troops on the long march to Texas. With his usual bravado, Santa Anna bragged to the British ambassador to Mexico that if the yanquis gave him any trouble he would plant the Mexican flag in Washington, D. C.

At San Antonio, the conquering Texans were under the command of Colonel J. C. Neill. As December drew to a close, 200 of the more restless volunteers had left San Antonio with the ambitious intention of taking Matamoros, a Mexican town located on the Rio Grande. Marching under the command of Colonel James Fannin (1804-1836), a Texas settler and slave trader who had graduated from the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, these men stopped in the Texas town of Goliad. (Others would gradually join to bring their number to about 350.) That left only a little more than 100 men at San Antonio, and these were short of food, medicine, horses, and adequate clothing for the surprisingly cold weather they faced. Still, most were in good spirits and fully convinced that the Mexicans would not return until spring. The Texans thought that the Mexicans would not make such a long, difficult journey over terrain made even rougher by winter.

Volunteers gather at San Antonio

Meanwhile, about 100 miles north of San Antonio, a big, friendly, feisty frontiersman named Sam Houston (1793- 1863; see biographical entry) had taken charge of the effort to organize a real Texan army. But this force was not yet fully formed or trained, and Houston let the leaders of the resistance fighters at San Antonio and other small towns know that they would have to stand on their own for a while. At San Antonio, more volunteers were slowly trickling in, including such notable figures as Davy Crockett (1786-1836)-a legendary soldier, frontier scout, and former Congressman who carried a rifle named “Betsy”-and Jim Bowie (1796-1836), who was known for the big hunting knife he carried, and which would forever after bear his name. Crockett arrived with a dozen of his fellow Tennessee volunteers, wearing his usual buckskins (a rugged frontier outfit made from deerskin) and asking, according to Don Nardo in The Mexican-American War, “Where’s the action?”

On February 2, command of San Antonio passed from Neale (who left to attend to family matters and also gather supplies for the town) to Colonel William Barrett Travis (1809-1836), who had just arrived with twenty-six volunteers. Tension between Travis and Bowie was resolved when the two agreed to a joint command. As the month progressed, the Texans received word that the Mexican army was on the march and moving fairly quickly. Sure enough, on February 23, a church bell alarm rang out when a sentry spotted a force of fifteen hundred cavalry (soldiers on horseback) approaching San Antonio. This was merely the advance guard of the six thousand troops Santa Anna was leading north.

Travis ordered the town of San Antonio abandoned, and he and Bowie, who was suffering from a bad case of pneumonia, led their 150 defenders across the San Antonio River to the Alamo, a deserted fort that had once been a Spanish mission (religious center). The Alamo consisted of a number of buildings set around a three-acre plaza (central, open area). The Texans mounted rifles as well as their fourteen cannons along the mission’s high walls, and they also raised their new flag, which featured a single, large, white star mounted on a blue background.

“I shall never surrender or retreat.”

That same day, the Mexicans took possession of the town of San Antonio and surrounded the Alamo. Santa Anna sent a messenger carrying a white flag (the universal signal for a pause in hostilities or aggression) and a message demanding that the Texans surrender. The Texans responded with a cannon shot that almost hit the messenger, an act that shocked and disgusted the Mexicans. The Mexicans now raised the red flag. This meant that they would take no mercy on their enemies, and their musicians began playing the ancient Spanish song “Deguello,” which is a call for bloodshed. Then the Mexicans began what would turn out to be an almost two-week-long bombardment of the Alamo.

On the morning of February 24, Travis wrote a desperate plea for help that a messenger boy managed to carry past the Mexican line and north to Sam Houston. As quoted by Lon Tinkle in The Alamo, he addressed his message to “the people of Texas and all Americans in the world,” reporting that he was surrounded by Santa Anna’s troops but that, despite twenty-four hours of bombardment, he had not yet lost any men. “Our flag waves proudly from the walls-I shall never surrender or retreat,” continued Travis, but he needed reinforcements. “I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due his honor and that of his country-Victory or Death!”

The bombing continued, but it was becoming clear to both sides that the Mexicans would have to launch a direct assault on the Alamo if they wanted to break this stalemate. On the evening of March 1, thirty-two volunteers from the town of Gonzales managed to slip through the Mexican lines undetected, bringing the number of defenders inside the Alamo to a little more than 180. Although none of the Texans had even been injured so far, they were running out of ammunition. The situation looked hopeless, for how could this tiny group possibly hold out against Santa Anna’s massive, and still growing, force? On March 3, Travis told his men that this would be a fight to the death, and he offered each of them the chance to leave, with no honor lost. It is usually reported that none accepted Travis’s offer, though some claim that one Texan did choose to leave.

A new battle cry: Remember the Alamo!

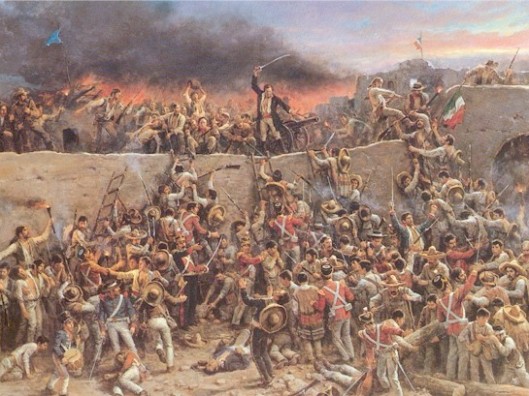

The end came on March 6. At about five o’clock in the morning, Santa Anna’s cannons smashed two huge holes in the Alamo’s walls, and somewhere between twenty-eight hundred and three thousand Mexican soldiers stormed the old mission. As they scrambled through the holes and over the walls, the Mexicans shouted, “Viva Santa Anna!” (Long live Santa Anna!). Travis is said to have turned to his men at this frightening point and urged them to “give ’em hell!” For a short time the Texans managed to keep up a steady and very damaging rain of bullets and cannon fire, but the struggle soon broke down into hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets and knives. Travis was shot as he was trying to load a cannon, and Crockett, after running out of bullets, was using his beloved “Betsy” as a club when he was finally surrounded and killed. Bowie died in the hospital bed he had been too sick to leave, but still managed to kill several of his attackers with his famous knife.

Within a half hour, the fight was over. One hundred eighty-two of the Alamo’s defenders were killed in the battle, and five more who survived were shot soon after the battle. Their bodies were burned. The Mexicans allowed Susana Dickinson, the wife of a Texan soldier who had been nursing Jim Bowie, and her baby to leave, as well as several Mexican women nurses and two slave boys. Meanwhile, the Mexicans had paid a high price for their assault on the Alamo. Although estimates of their losses vary, most historians agree that about six hundred Mexican soldiers lost their lives.

Even before the Mexicans’ main assault on the Alamo had begun, an important meeting took place in a blacksmith’s shop at Washington-on-Brazos, a town located about 150 miles northeast of San Antonio. There, on March 2, representatives from various parts of the colony had declared Texas independent from Mexico. This new nation was to be called the Lone Star Republic. Modeling their constitution closely after that of the United States, the Texans named David Burnet (1788-1870) their temporary president, and made Sam Houston commander of their army. That army would soon have a powerful rallying cry, for news of the massacre at the Alamo reached them several days after the battle took place. Now Texans would yell “Remember the Alamo!” as they faced their enemy, and the old mission would become a symbol of sacrifice and the struggle for freedom for the Texans and their sympathizers.