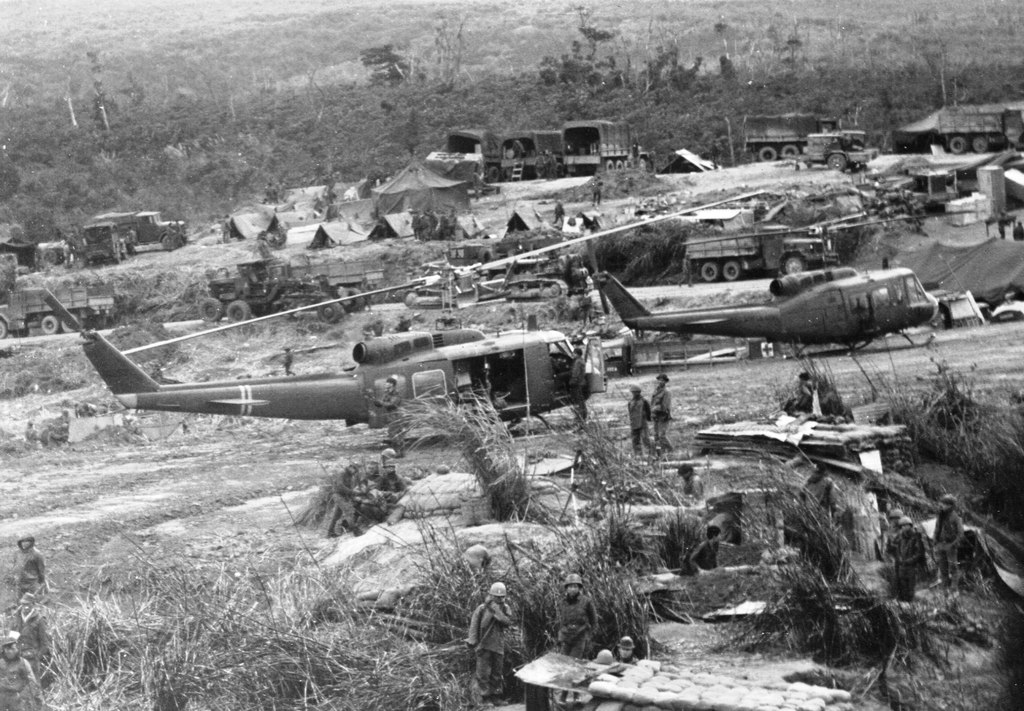

Helicopters and supply vehicles at Khe Sanh, 12 February 1971

Date: February 8-March 25, 1971

Location: Laos

OPPONENTS 1. South Vietnam Commander: General Hoang Xuan Lam

2. United States Commander: General Creighton Abrams

3. North Vietnam Commander: Le Trong Tan

Lam Son 719 was the first major test of the U. S. Vietnamization policy. Elements of the 1st Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) Corps were supposed to interdict a portion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the supply route for the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in southeastern Laos. Both sides claimed victory, but it is generally acknowledged that the PAVN won the battle.

The Cambodian Incursion (April 29-July 22, 1970) to disrupt PAVN supply operations in Cambodia, despite the domestic political fallout in the United States, was deemed a success by President Richard Nixon, as well as by the commander of Miltary Assitance Command Vietnam (MACV), General Creighton Abrams. In late 1970, a similar operation was proposed for southeastern Laos, near the DMZ. In December, President Nixon gave his consent to the operation, and planning began for a joint ARVN-MACV cross-border attack. However, the Cooper-Church Amendment passed and signed into law on December 22, forbid U. S. ground forces from operating in Laos and Cambodia, but it did allow the United States to provide air and indirect fire support to ARVN forces. The plan then became an ARVN operation backed by U. S. air and artillery support.

The plan called for the 1st ARVN Corps to attack along Route 9 to seize Base Area 604 near the abandoned village of Tchepone. After seizing Base Area 604, the ARVN forces would remain in the area until the start of the rainy season, interdicting the Ho Chi Minh Trail and destroying other PAVN supply bases in the area. To accomplish the mission, the 1st ARVN Corps would insert airborne and ranger units in a series of blocking positions to protect the right flank of the main armor force attacking along Route 9. At the same time, units from the ARVN 1st Infantry Division would be airlifted into blocking positions along an escarpment on the left flank of Route 9. Then the armored formation would drive directly to Tchepone, where the Corps would consolidate and continue operations in the area.

Even though U. S. ground forces could not enter Laos, Operation Dewey Canyon II called for a brigade from the U. S. 5th Infantry Division (ID) to clear routes up to the border and reoccupy the fire base at Khe Sanh to assist and provide indirect fire support to the 1st ARVN Corps units as they crossed the border. Also, the U. S. 101st Airborne Division would provide aviation support to the 1st ARVN Corps. The helicopters from the aviation brigade of the 101st were augmented by fixed-wing aircraft from the USAF and USN. Operation Dewey Canyon II began on January 30, and within a week, the 1st Brigade of the U. S. 1st ID seized Khe Sanh and cleared the routes to the Laotian border. The route was clear for the 1st ARVN Corps to begin Lam Son 719 on February 8.

After the success of the Cambodian Incursion the previous year, the PAVN anticipated that the U. S.-backed ARVN forces might try a similar operation on Laos. To counter any ARVN attack, the PAVN activated 70B Corps and assigned the 304th, 308th, and 320th divisions, augmented with armor, artillery, engineers, and antiaircraft units, to the vicinity of Base Area 604. These divisions would prove critical in the upcoming battle. However, when the battle commenced, there were only approximately 10,000 PAVN soldiers in the immediate area of Tchepone. Roughly half were combat soldiers, and the remainder were support troops operating the supply base.

The ARVN advance on February 8 was preceded by a massive artillery bombardment that included eleven B52 Stratofortresses bombing in the tactical role. After the fires lifted, the lead elements of the ARVN armored brigade crossed the Laotian border along Route 9. Simultaneously, the first units of ARVN Rangers were air-landed into their blocking positions north of Route 9, and units of the ARVN 1st Division were doing the same south of Route 9. Artillery was airlifted into position once the infantry had established their fire bases.

For the first few days, ground fighting had been relatively light as the PAVN took time to analyze the extent and direction of the ARVN attack. In the air, though, it was a different story. PAVN antiaircraft gunners brought down seven helicopters and damaged several more. Still, the ARVN and MACV commanders were pleased with the success of the 1st ARVN Corps on the first day. However, it did not take long for the situation to change.

For some reason, the advance of the armored column slowed, and the tankers did not link up with the paratroopers at Ban Dong, halfway to Tchepone, until February 10. At the time of the linkup, there were approximately 10,000 ARVN soldiers in Laos. Along with Ban Dong, the ARVN occupied ten blocking positions protecting Route 9. After the linkup, the armored column moved about 5 kilometers outside of Ban Dong and halted. The commander of the column was waiting for orders from General Lam before continuing, so they waited along Route 9 for orders that were not forthcoming. Unknown to the armored column, other intrigues were taking place behind the scenes.

Following a series of intense firefights between the ARVN and PAVN the previous days, the president of South Vietnam, Nguyen Van Thieu, flew out to the 1st Corps headquarters to confer with General Lam. Thieu, concerned that a large number of casualties could affect the upcoming election, warned Lam to be cautious. Before he left, he told Lam to call off the operation if his casualties exceeded 3,000. Meanwhile, in the United States, defense secretary Melvin Laird told reporters that the halt was merely a pause in order to assess the enemies’ reaction to the incursion.

The PAVN reaction was slow as the 70B Corps commander evaluated whether the attack was the main effort or a diversion. However, after determining that Lam’s attack was the main effort, the PAVN reacted quickly. Aided by the ARVN halt, the PAVN moved the 308th Division into the area from the north, and the 2nd Division moved to Tchepone from the south. More ominously, they moved more antiaircraft guns into the hills around the ARVN corps.

With the ARVN stalled and fresh reinforcements arriving, the initiative shifted to the PAVN. They began their counterattack by putting pressure on both flanks. In the north, the PAVN would isolate the individual fire bases from aerial support with antiaircraft fire. Then they would overwhelm the defenders with indirect fire before overrunning the ARVN outpost with ground forces. All the while, they maintained pressure on the southern flank. The ARVN’s position in Laos was becoming tenuous.

On February 19, President Thieu revisited Lam. This time, Lam painted a bleak picture, emphasizing the continuous flow of PAVN reinforcements into the area. Lam warned the president that it would be risky to continue the advance toward Tchepone. Before he left, Thieu advised Lam that he should take his time and perhaps shift his effort to the southwest. Meanwhile, desperate fighting continued on the flanks of the 1st ARVN Corps.

By the end of February, the PAVN had overrun several of the fire bases and was heavily engaged with the 1st ARVN Corps when Thieu intervened once more. This time, he suggested that Lam conduct an airmobile operation to seize Tchepone. Thieu believed that seizing Tchepone would give him enough political cover to declare the operation a success before withdrawing Lam’s corps back to South Vietnam. The plan called for elements of the 1st Division to be inserted into a series of landing zones (LZs), culminating in the occupation of Tchepone. The assault would be the largest airmobile operation for the U. S. army during the war.

The attack began on March 3 with the insertion of elements of the 3rd Battalion 1st Infantry Regiment into LZ Lolo. All went well with the first lift, but the second lift ran into the alerted PAVN air defenses. By the end of the day, LZ Lolo was secured, but the eleven helicopters were lost and forty-four damaged in the process. It was not an auspicious beginning to the operation. Two days later, elements of the 2nd Regiment were airlifted into LZ Sophia, 4.5 kilometers southeast of Tchepone. However, another nine helicopters were lost, and the remainder incurred varying degrees of damage. Despite the loss of so many helicopters, the ARVN was setting the stage for the final assault on Tchepone.

On March 6, another 5,000 ARVN soldiers from the 2nd Regiment landed on LZ Hope. The next day, the ARVN occupied Tchepone, inflicting significant casualties on the PAVN as well as disrupting their supply operations in the area. The 1st ARVN Corps had achieved its objective, and Thieu could claim the operation as a success. Thieu promptly ordered the withdrawal of Lam’s corps. Unfortunately for the ARVN, the PAVN had moved over 60,000 soldiers, along with two tank regiments and nineteen antiaircraft battalions, into the area, hoping to cut off the 1st Corps’ retreat.

A withdrawal under contact is one of the most challenging operations for an army to execute. There is always the risk that an orderly retreat will turn into a rout and an unmitigated disaster. On March 9, the units of 1st Corps began withdrawing from Laos. The PAVN kept up the pressure on the retreating South Vietnamese soldiers. On the flanks, the fire bases fell one by one. The PAVN overran some, while in others, the defenders were able to fight their way out and continue their retreat. Route 9 quickly became clogged with destroyed or abandoned vehicles as the battered corps found its way back to the border. Some units panicked, while others fought with distinction; regardless, the retreat from Laos could not be considered a bright spot for the South Vietnamese army. On March 25, the last 1st Corps unit left Laos, and Lam Son 719 was over.

Lam Son 719 lasted forty-five days, and both sides claimed victory. President Thieu called it “the biggest victory ever,” while President Nixon used the battle to declare that “Vietnamization has succeeded.” Neither president was correct. Some estimates claim that as much as half of the PAVN forces became casualties, and over 7,000 of the 1st ARVN Corps were killed, wounded, missing, or captured. The ARVN lost fifty-four tanks, ninety-six artillery pieces, and nearly 300 other vehicles. Nevertheless, the most significant figure was in rotary-wing aircraft losses: Combined, the U. S. army and ARVN lost 168 helicopters altogether and 618 were damaged, many beyond repair.

However, the biggest loser was the concept of Vietnamization (Nixon’s optimism notwithstanding). Lam Son 719 made it evident that the ARVN was not ready to conduct operations on its own, without significant American support. Nonetheless, the United States was committed to withdrawing its forces from South Vietnam. Despite its losses, North Vietnam declared victory. For a time, the ARVN’s operations disrupted the PAVN’s supplies, but this only delayed their upcoming 1972 offensive. After Lam Son 719, the strategic initiative was in the hands of Hanoi.

Further Reading Sander, Robert D. Invasion of Laos, 1971: Lam Son 719. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014. West, Andrew A. Vietnam’s Forgotten Army: Heroism and Betrayal in the ARVN. New York: New York University Press, 2008. Willbanks, James H. Abandoning Vietnam: How America Left and South Vietnam Lost Its War. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004. Willbanks, James H. A Raid Too Far: Operation Lam Son 719 and Vietnamization in Laos. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2014.