The years from 1939 to 1945 may well have seen the most profound and concentrated upheaval of humanity since the Black Death. Not since the fourteenth century had so many people been killed or displaced, disturbed, uprooted, or had their lives completely transformed in such a short space of time. The years at the very end of the war, and immediately following it, once more illustrated the old adage that it is quite possible to win the war and lose the peace.

The areas where the war was actually fought lay in ruins. Northern France, the Low Countries, the great sweep of the North German Plain, and a wide swath running all the way to Moscow and Stalingrad lay devastated. In the countryside it was not so bad; targets had been fewer, and there were substantial areas that had been bypassed by the fighting. The farther back in the country one lived, and the more basic one’s life, the less likelihood there was of its being disrupted. But the cities were heaps of rubble, railways were lines of craters and twisted rails, bridges were down, canals and rivers blocked, dams blown, and electric power grids destroyed. Most of the paraphernalia of modern society was damaged to greater or lesser degree.

Across the world in the Pacific and east Asia it was the same. Inestimable amounts of property damage had been done, huge nations—China and Japan—and the great empires of the colonial powers were all brought low. Millions of starvelings shambled among the ruins, seeking some way to put their lives back in order.

Yet the damage was by no means universal. Those countries of the industrialized world that had fought in the war, but had not experienced any fighting on their own soil, had prospered almost in direct proportion as the combat zones had suffered. If in Europe and Asia it might be hard to tell the winners from the losers, there was absolutely no question that the North Americans were winners.

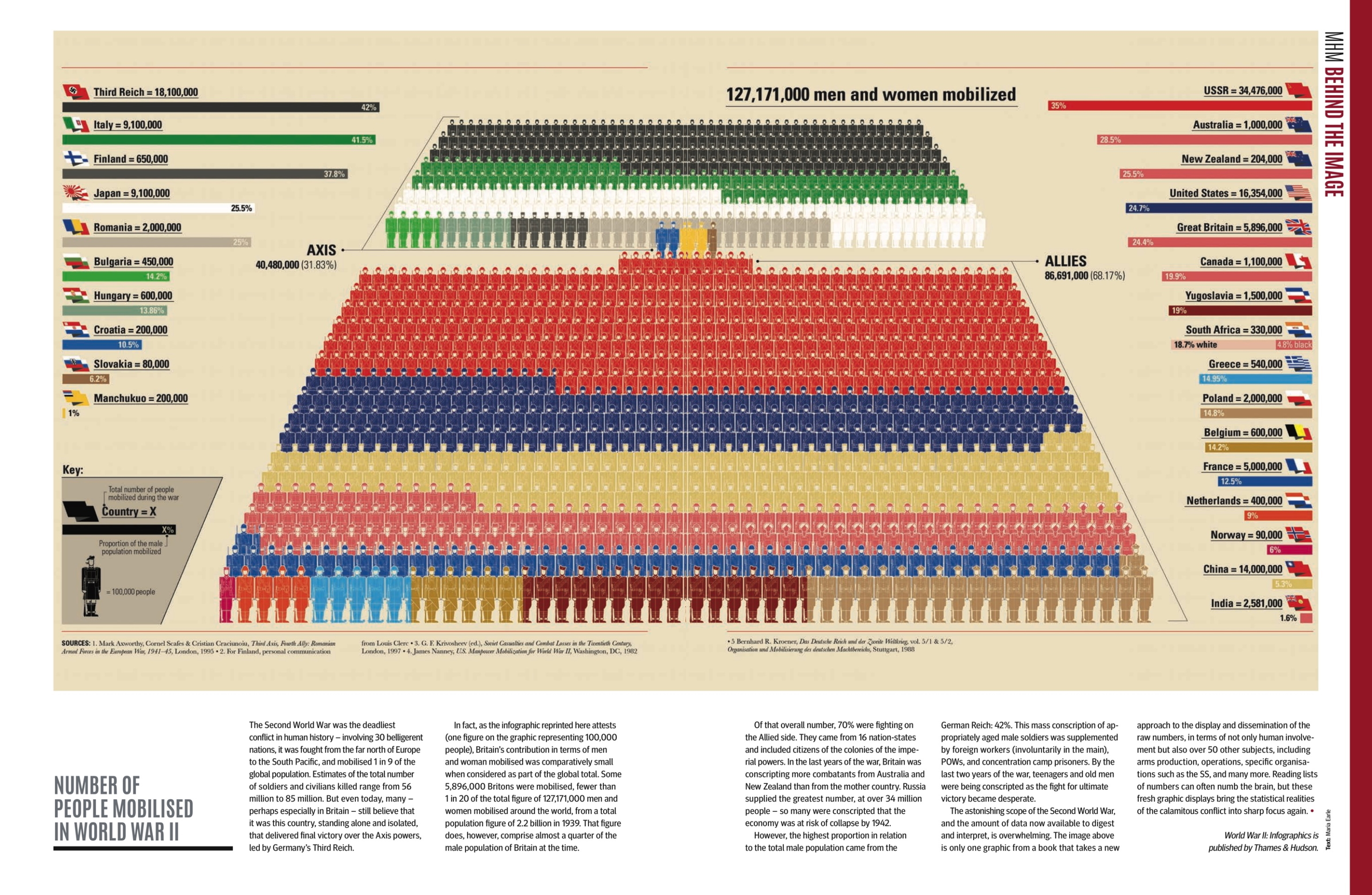

Some of the tale, if by no means all, is told by the casualty figures. About seventy million men, at one point or another throughout the war, had borne arms. Roughly seventeen million of them were killed by the war, along with at least another twenty million or more civilians who had the misfortune to live in the wrong place at the wrong time.

These casualties were extremely unevenly divided. On the Axis side Germany mustered nearly twenty million soldiers, though her peak strength at any one time was just over ten million. Three and a quarter million died in battle, slightly more than that from nonbattle causes, and seven and a quarter million were wounded. Over another million were “missing”; they simply disappeared. The Homeland was utterly devastated, unlike in World War I when the Germans had fought the war on other people’s soil. The Italians had put just over three million men in the field and suffered casualties of just over 10 percent, about half of which were deaths. The navy and merchant marine were gone, and the country from Salerno to the Po Valley had been fought over. Italian figures ironically had to be entered on both sides of the ledger. By far the greatest portion of her losses were incurred in the Axis’ interests, but she also had 20,000 deaths while fighting on the Allied side after 1943.

Japan had put nearly ten million men in service; her peak strength at any one time was just over six million. Her casualty figures were incredibly distorted by western standards. In European armies it was normal to suffer two or three wounded for every death, especially in this war where battlefield medicine and new drugs came into prominence. But Japan had almost two million military deaths, and only 140,000 wounded. About half a million civilians were killed in the bombing campaign, and more than 600,000 wounded. Additionally, well over a quarter of a million Japanese taken prisoner at the end of the war by the Russians as they moved into Manchuria were not returned to Japan.

In human terms, the price of victory for the winners was as high as that of defeat for the losers. China had lacked the industrial potential to mobilize as many men as her population would otherwise have supported. The greatest number reached by the Chinese armies never exceeded much over five million. Yet her war had gone on ever since 1937, and she had more than two million deaths in battle. With primitive medicine and conditions, many of her soldiers who died would have lived had they been in a European army. Her civilian deaths from bombing and military action, or from the indirect consequences of war and its upheaval such as starvation, were never counted, but must have numbered well over five million and may have been ten million.

Of the European allies, Poland had merely exchanged two conquerors for one of them; in a sense the entire population of Poland could be numbered among the casualty figures. France did better. The French collapse had been mercifully quick, though “merciful” was hardly the term one would have applied at the time. At their peak the French mustered five million men under arms. Roughly a quarter of a million were killed in battle or died from other causes; another half million were wounded or missing. Nearly half a million civilians were either killed or deported to Germany for shorter or longer periods. Thirty thousand French men and women were shot by firing squads. The northern part of the country had been fought over twice, the second time especially destructively as a result of the Allied air interdiction campaign. Industrial France was nearly as devastated as Germany. In spite of the physical destruction though, France was not as badly off after World War II as she had been after the first war. She was not entirely a country of old men and widows. Yet the second battle had sapped her vitality almost more than the first one, and the postwar governments found themselves forced into strenuous efforts just to get Frenchmen to reproduce. Building up families hardly seemed worthwhile to many if they were to be cannon-fodder every generation.

Britain had had her finest hour, and she had paid grievously for it. Her merchant fleet was cut nearly in half in spite of wartime building, many of her cities were extensively damaged, her national debt had risen to the stratosphere, her great financial holdings had disappeared. She had mobilized nearly six million men, and a quarter million of them had died in Europe, in North Africa, and in Burma. Another 400,000 were wounded or missing. As with France, the bill had been far short of that for World War I, but in 1918 the British had at least possessed the satisfaction of being sure they were the winners. In 1945 it looked instead as if they had exhausted themselves only to give way to the United States and Russia.

Of the two new superpowers, Russia had had the deeper wounds. Stalin said that Britain paid for the war in time, the United States in materials, and the Russians in blood. More than six million Soviet soldiers died and more than fourteen million were wounded. Well over ten million, perhaps as many as twenty million, civilians were killed by the war and the callous policies of both their own and their enemy’s governments. Nearly a million square miles of Russian territory lay devastated. More Russian soldiers died in the one great battle for Stalingrad than Americans did in all the battles in the entire war.

The United States too had paid heavily for her part in the war. Her great advantage lay in the two huge oceans that protected her. Except for an attempt by one submarine-launched Japanese seaplane, notable only for its uniqueness, and the ill-fated Aleutian campaign, no bombs had fallen on the American continent. The only enemy soldiers to set foot in the United States were prisoners of war, delighted to be there. More than sixteen million Americans served in the armed forces; 400,000 of them died, and more than half a million were wounded. It was the most costly war in American history up to that point, far more so than World War I, and nearly equaling in deaths the losses on both sides of the American Civil War. For a people who, as late as December 6, 1941, had thought it was not their war, the Americans had made a major contribution to the Allied victory.

They had also made an immense profit from it. One of the great ironies of the American war effort was the way it was borne disproportionately by a relatively few people. In spite of the huge numbers of men in service, second only to Russia among the Allies, only a limited number of them saw combat. Those who did saw probably far too much of it. Infantrymen grumbled about the air force policy of rotating men home after fifty combat missions, but that was much fairer than leaving soldiers in combat units until the war either killed them or ended. For the vast majority of Americans it was a good war, if there can be such a thing. People were more mobile and more prosperous than ever before. The demands of the war brought the United States out of a deep depression, created new cities, new industries, new fortunes, a new way of life. Families and friendships were strained by the disparities of fate, and after the war the government passed a wide range of legislation in what was really an attempt to allow those who had fought for twenty-one dollars a month to catch up with those who had stayed home and made ten times that much.

With the end of the war there began a vast folk wandering. At its most organized it consisted of such incredible organizational feats as “Operation Magic Carpet,” by which the United States brought huge numbers of soldiers back home from the distant battle fronts. Day after day the ships steamed into New York, or Hampton Roads, or San Francisco, and disgorged their hordes of khaki and olive-drab cargoes. The immense processing machine that had turned them into soldiers, sailors, and Marines a world ago now turned them back into civilians, gave them their back pay, papers that said they were entitled to the small bits of ribbon that meant so much to them and so little to others, other papers that said they had served their country honorably and well, and turned them loose to pick up the threads—if they could find them—of their former lives. Most of them made the transition easily; the “trained killers” prophesied by some psychologists quickly turned out to be normal young men, though they told some bizarre stories and were apt to be impatient when reminded by salesmen that prices had risen “because there’s been a war on, y’ know.” The demobilization of the Allied armed forces was by no means the least spectacular of operations carried out in the course of the war, and in most places it was carried out with impressive smoothness. In the United States alone, nine million men were back in civilian life in less than a year.

At the other end of the scale this migration consisted of millions of uprooted Europeans and Asians, trying desperately to get to homes and families that in many cases no longer existed. Long columns of people—ex-prisoners, freed slave laborers, orphans, widows, old people—straggled along the roads of Europe, fleeing the Russians still or trying to get back to Poland or Rumania. In the cities the survivors poked aimlessly among the rubble. The German governmental organization had stood up under the Allied attacks until the very end of the war, but with the collapse of the regime everything else seemed to collapse as well. The conquerors soon found themselves, with good or ill will, organizing a new life for the conquered. “Displaced Person” camps were established, the enemy peoples were screened as to their roles under the former governments, public services were reestablished, war trials were initiated, and the victors, with the help of the vanquished, were soon busily engaged in sorting out the spoils and the debris.

Just as individuals benefited or suffered disproportionately from the war, so did nations. As the European war neared its end, the Allied leaders had turned their attention to postwar problems. There had been assorted ideas of what to do with Germany, the most famous of them probably being the plan by the American Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, that Germany ought to be stripped completely of her industrial capacity and turned into a pastoral country, transformed from industrial giant into operetta-sized states. Such an attempt to turn the clock back a hundred years was doomed to failure, but was typical of at least one end of the spectrum of ideas about the Germans.

Throughout the war substantial numbers of Allied officials had tried to deal with the problems foreseen for the postwar situation; to some extent they succeeded, but to a larger extent, they were outpaced by events. As early as December of 1941 Joseph Stalin had tried to get the British to agree that at the final reckoning, Russia would be left in possession of everything she had held at the start of hostilities—her start of hostilities, which would have given her all the Baltic states and most of eastern Poland—plus major acquisitions at the mouth of the Danube. At that time and through most of 1942, Russia was carrying the major burden of the conflict, and it was obviously in her interest to settle the future while that was still the case. With German soldiers but a few miles from Moscow, Stalin could point to the immense sacrifices his country was making, and demand equally immense rewards. For that very reason the British and the United States preferred to wait before settling anything definitively.

In May of 1943 the Soviet Union dissolved the Comintern, or “Communist International” office, the organization responsible for encouraging the spread of communism abroad. This was designed to reassure Russia’s partners of her increasing respectability, and in October, when the Allied Foreign Ministers met at Moscow, the Americans, British, Chinese, and Russians—the wartime “Big Four”—announced they would not resort to military force in other states for selfish purposes after the end of the war. This Moscow meeting was a preliminary for the Tehran Conference, and at Tehran Stalin agreed he would take part in the United Nations. Problems over who would be admitted and what kind of powers each state should have plagued the early discussions on the organization; at one point the Russians wanted a seat in the assembly for every “republic” of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, whereupon the United States replied that then the Americans must have a seat for every state of the union. This kind of difficulty, and especially the veto question, haunted both the Tehran meeting, and even more the Yalta Conference held in February of 1945. By that time it was obvious that there were to be four major trouble spots.

The most distant of these was Japan. The Americans expected to have to invade Japan and wanted Russian help to do so. The Russian price was higher than the Americans wished to pay—southern Sakhalin, the Kurile Islands, and concessions in Manchuria. The dilemma they faced over Japan made the Americans much more susceptible to Russian demands in Europe than they might otherwise have been. They did not at this time have the atomic bomb. In February they had instead the fanatical resistance on Iwo Jima to deal with.

A second thorny question was the perpetual one of the Balkans. The Western Allies had no wish to see the Russians on the shore of the Mediterranean, but their view was compromised by the fact that the Communists had been the most effective anti-German fighters in the Balkan states. In December of 1943 Stalin had agreed that the Russians would not dominate Czechoslovakia. In October of 1944 he and Churchill met at Moscow and Churchill slipped him the famous piece of scratch paper which said that Russia could dominate Rumania and Bulgaria, Britain would dominate Greece, and they would split the difference in Yugoslavia and Hungary. Actually, the Russians got all but Greece, where the British landed troops in the middle of an incredibly chaotic turmoil, and Yugoslavia, where Tito’s brand of native communism was strong enough for him to stay clear of the Russians’ embrace. The final determinant on the Balkans, as elsewhere, was who had troops on the ground and was strong enough to keep them there.

The major impediment to Allied harmony continued to be Poland. Relations between Stalin and the legitimate Polish government-in-exile in London had gone from bad to worse. From demanding that Russia’s western border be the Nazi-Soviet demarcation line of late 1939, Stalin went to setting up a rival Polish Communist government, to letting the Warsaw Poles destroy themselves in the premature rising against the Germans. There was absolutely nothing the British could do about it. Poland was as far beyond their reach in 1944 and 1945 as it had been in 1939. At Yalta the Big Three—Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill—the latter two reluctantly, agreed that Poland was a Russian sphere of influence. In terms of the reasons for which she had declared hostilities in 1939, at Yalta Britain conceded that she had lost the war. The Western Allies then compounded their defeat over Poland: they agreed to repatriate, often against their will, Poles and other east Europeans who had fought on the Allied side. Many of those who had given so much for Allied victory got their rewards in Russian labor camps.

By the time the loss of Poland was accepted, Germany was collapsing. The Allies had reached some common agreement on the postwar policy to follow: denazification, disarmament, demilitarization, punishment of war criminals, reparations, and dismantling of war industries. Britain had suggested in 1943 that Germany should be occupied this time, and the idea had been refined through 1944. The occupation zones were formalized at Yalta, with the British and Americans taking a lesser zone to give the French a share. Both Berlin and Vienna were to be administered by a quadripartite agreement. The divisions were as much in response to the existing situation as anything; for example, the United States took the southwestern zone because American troops were on the Allies’ right flank. The question of access to Berlin did not seem especially troublesome; they agreed that Russia and the government of the Polish state—whoever should form it—would divide Prussia between them. Since it was their Poland, the Russians got the frontier between Poland and Russia that they wanted, and then obligingly moved Poland’s western frontier that much farther into Germany. The Allies never got to a definitive agreement on reparations or deindustrialization, in spite of having initially agreed they wanted both. In all four of the major areas, as soon as the euphoria of victory wore off, the basic rifts in the Allied views were bound to emerge, and they did so.

Nor were these by any means the only problem areas. Of almost equal complexity were the questions of what to do with the former colonial empires. The British, the French, and the Dutch might all think that they were going to move back into Southeast Asia and the islands and go on as they had before the war. The local inhabitants felt differently. One of the reasons the United States had been reluctant to have British units operating with it in the Pacific was that Americans tended not, even after their wartime cooperation, to be overly sympathetic to British ideas of empire. The Americans had promised independence to the Philippines, and after the war they granted it. The British did not want to see their empire go.

They recognized it could never be quite the same again, but it was one thing to recognize that rationally, and another to slide back into a peace of exhaustion and a third-power status, as if Great Britain were Switzerland or Sweden. They knew the inhabitants of the empire were profoundly stirred by the war. On the one hand there had been the immense contributions of Indian and colonial troops, the great strides made in the modernization of Indian industry. On the other there had been the destruction of the great myth, that some men are inherently superior to others because their skin is white. Without the acceptance by both parties of that myth, colonialism was no longer possible, and Burmese or Indians who had watched long pathetic columns of British and Australian prisoners being prodded along by stolid Japanese could never accept the myth again. There had been great unrest in India during the war; Churchill’s government had sent out Sir Stafford Cripps to talk to the Indian leader, Mohandas Gandhi. Cripps was hardly the man for the mission—Churchill once remarked of him, “There but for the grace of God goes God”—and when he promised Gandhi independence after the war if India helped win it, Gandhi castigated the offer as “a post-dated check on a crashing bank.” India wanted out of the empire, and Britain would no longer be able to hold her in. Burma went too, and eventually so did most of the rest of the nonwhite areas.

If the British ultimately faced colonial realities, the French and Dutch resolutely refused to. Even more than the British, they needed their empires to bolster their sagging self-esteem. The Dutch came back to the Indies to find the British engaged in desultory operations against the Indonesian nationalists. The Dutch took over the fight, which lasted in an on-again off-again fashion until 1950. The French finally got forces back into Indochina to find near-chaos. The old prewar garrisons had held on, under Japanese domination, until 1945. The Japanese had then imprisoned and massacred most of them. The few survivors and escapees made their way to Chinese Nationalist lines, where they were received as allies. Then they were turned over to the arriving Gaullist French, who imprisoned and tried them as Vichyites. Meanwhile, at the Japanese surrender the British moved forces into southern Indochina, and they eventually handed over power to the French. Northern Indochina was occupied by the Nationalist Chinese, and they, instead of waiting for the French, gave over the reins to the Indochinese nationalists, led by a local guerrilla named Ho Chi Minh. Negotiations between the Indochinese and the French broke down, and late in 1946 they started shooting at each other, in a war that went on until 1954. The residual legatees of the fighting were the Americans, and they in turn got involved in a war that in many ways would scar the United States more than World War II had done.

Nor was fighting and confusion confined to Southeast Asia. The Japanese collapse in China was nearly matched by the exhaustion of Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists. As the Russians declared war on Japan and flooded down into Manchuria, the Chinese Communists, who had virtually sat the war out in northeast China, now emerged once again. They and the Nationalists were soon locked in a battle which ended only in 1949, when the remnants of the Nationalists fled to Formosa, and the Communists definitively took over mainland China. By then, the Cold War had already begun; in both Europe and Asia the powers of the West appeared in disarray and on the defensive. How, men asked, could so much have gone wrong so quickly?

For many Europeans or Asians, the answer to that question was simple: it was all the fault of the Americans. They were big, brash, bumbling innocents in the international jungle. All they wanted to do after the war was go home and forget about it. Few of the writers who took this line seemed to carry it to the logical conclusion. It was more soul-satisfying to berate the Americans for being excessively well-behaved internationally than to castigate the Russians for being extremely ill-behaved internationally.

In fact, the United States and its leaders did make a whole series of mistakes and misassessments. The basic one was in assuming that Soviet Russia was very much like themselves. They thoroughly underestimated the paranoia that resulted from a combination of the traditional Russian fear of invasion from Europe and the outcast nature of communism itself. They equally underestimated the degree to which all their other allies were exhausted. They believed that Great Britain and France and Italy all ought to be able to fend for themselves now that the crisis was over. They cut off Lend-Lease to Britain, bringing about a near-collapse of the island’s economy; they turned over a large part of their occupation zone in Germany to the French. President Truman was unpopular, and the American public wanted an immediate end to wartime measures. Few people realized how close to complete collapse western Europe was. The same thing happened in China, where it looked as if the Chinese Nationalists and Chiang Kai-shek ought to be able to put their own house in order at last. In fact they failed miserably, due more to their own inherent weaknesses and shortcomings than anything else, and China went Communist by the end of the decade.

If the Americans made mistakes in their response to the immediate postwar situation—and assuredly they did—they were largely tactical mistakes. On a longer view the picture looked different. The brilliant foreign servant George F. Kennan pointed out in one of his books that much that happened at the end of the war was the result of the line-up of participants during it. The fact was that all the democracies, if they had hung together, were still not strong enough to defeat all the totalitarian states, if they had hung together. In a long fight, and barring the sudden advent of nuclear power on only one side, the United States, Britain, France, and China, could probably not have defeated Germany, Italy, Russia, and Japan. It was Hitler’s falling out with Stalin, and the great Russo-German war, that upset this equation, and only with the aid of one of the two major totalitarian states could the democracies defeat the others. That being the case, and the Stalinist dictatorship remaining the Stalinist dictatorship, the same country that had purged its hundreds of thousands before the war, it was inevitable that at the end of hostilities the Russians would seek to gain as much as they could in as many places as they could. Churchill, who had some growing awareness of the problem, fell from power at the end of the war, and Britain no longer had the strength to stop the Russians even had she possessed the will to do so. Churchill had spoken perhaps more presciently than he realized when he said that if Hitler invaded Hell, Churchill would make favorable reference to the devil. At the end of the war the Soviet “devil” simply called in his bills. Between an exhausted east Asia and west Europe, and a United States which did not realize the true nature of its ally—any more than anyone else had really done—the Communists got a great deal of what they wanted.

One more of the reasons they did so was that the war had created two huge power vacuums. In Europe the always-delicate equilibrium between France, Britain, Germany, and Russia had now been destroyed. This was hardly realized by the Americans, and the result was a flow of the remaining power, Russia, into the vacuum. Only when the Americans recognized that western Europe itself might well be overrun did they reverse their immediate postwar policies and start their own return into that vacuum, by means of increased troop commitments, through NATO and various other regional pacts, and through the Marshall Plan, which helped Europe immeasurably toward recovery. Finally, they found it necessary to rebuild what is now the major power of western Europe, West Germany, and the irony of history and geography came full circle.

Traditional power structures were disrupted in Asia as well. Japan and China had balanced each other off throughout the last century. Now Japan was utterly defeated, occupied by the United States, and China was in a state of near-collapse. The Communists moved into China, with some Russian support, but soon developed an independent Chinese line. And the United States suddenly found itself the heir of Japan’s defense problems. Before 1941 the United States’ military frontier had been somewhere in mid-Pacific. Now it had moved forward to the Asian rim—to Korea, the Formosa Strait, and ultimately, as the colonial powers receded from the area, to Vietnam.

In both Europe and Asia, it would only be as the local powers slowly regained strength that the two superpowers would be able to disengage, the Americans more or less willingly, as they tried to get NATO to take more care of itself, or as they attempted hesitantly and not entirely successfully to withdraw from East Asian adventures, and the Russians unwillingly. In fact, the Russians tried to ease off in the mid-fifties, but found that it was impossible to lessen the pressure a little bit, for fear the whole system would blow up on them. Hence the repression of Hungary in 1956, where they slammed the lid back down, and the later repeat performance in Czechoslovakia in 1968. After such a major dislocation as that of 1939-45, it was inevitable that there should be a long and complicated working out of the new power realities, a working out that has taken much longer than the fighting of the war itself.

What, then, was it all for? Were the old diplomatic deals merely to be repeated with new participants? Were so much suffering and sorrow, so much sacrifice and bravery only of concern to the unwitting pawns in the game? Was the cynicism of the definition of a war crime—that it was something committed by members of the Axis—to triumph after all? Was there in the last analysis no difference between the one side and the other?

In 1784 an innocuous-appearing German professor in Konigsberg published a short article. The professor’s name was Immanuel Kant, and the article had the tortuous and eminently German title of “Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Intent.” In it Professor Kant took issue with the current Enlightenment fiction that if society could only get rid of a few more evils, Utopia was just around the corner. Utopia, he said, will never arrive. Progress there is and undeniably so. But every step forward to a new level of progress, every solution to one generation’s difficulties, brings with it a new set. Each era has to solve its own problems, and in doing so it uncovers or even creates problems for its successors. World War II certainly created as many problems as it solved; in fact, as most wars seem to do, it may have created more. That does not mean it was not worth fighting, or need not have been fought. Evil does exist in the world—it undeniably existed in Hitler’s world of death camps and extermination groups—but without the possibility of evil, there is no true choice and no true freedom. In its basic definition, “Freedom” means the right to choose one’s own way to die. The servants of the dictators left that choice to their masters and fought and died for causes that even they themselves often found odious. The men and women of the free nations who fought World War II chose their own doom. If they could not destroy every evil, they destroyed the most vicious of their day. If it is part of the sadness of the human condition that they could not solve the problems of their children’s generation, it is part of the glory of it that they so resolutely faced their own.