The Chinese, aware that the armistice is near, continue to find a weakness along the lines to snatch a major victory during the waning days of the war. Recently, fresh troops in the form of the Chinese 1st Army (Chinese 1st, 2nd and 7th Divisions) had arrived to relieve other Chinese units, providing the Communists with extra incentive to launch an attack.

The enemy had also been broadcasting demands for surrender, offering the 7th Division units a choice, either surrender or die, as well as other intimidating threats; however, the Chinese had made similar threats all during the conflict and in most cases, it was the enemy which paid the ultimate price. In this case, the men of the 17th Regiment ignore the threats. The threats are received with equal attention that is given to the Chinese bugles. At times, during some battles, the Americans actually acquired Chinese bugles from enemy troops that no longer had use for them and the Americans would use the confiscated bugles to confuse the enemy.

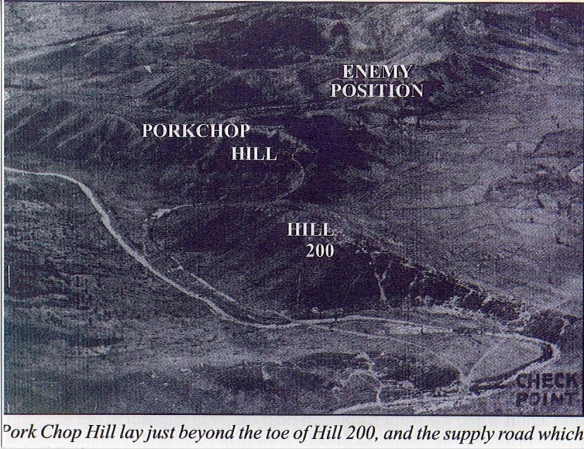

On this day, subsequent to dusk, the Chinese mount a major assault against a coveted outpost in the 7th Division’s zone, Hill 255, known as Pork Chop Hill. Earlier, during the previous March, the Chinese failed in a similar attempt. On this day, subsequent to dusk, amid a miserable torrential rainstorm, the Chinese commence a massive artillery and mortar bombardment that crashes all along the perimeter of the 7th Division. However, the main objective is the outpost on Hill 255, about 500 yards to the front of the MLR and near the enemy-held Old Baldy. Encouraged by the shrill sounds of whistles, the blare of the Chinese bugles and the vociferous shouts of prodding officers, the infantry charges forward, oblivious to the return fire and obstacles, including barbed wire.

Some forward detachments of the company-sized defending force, the first to see the approaching hordes, make it back to the main defenses, manned by Company A, 1st Battalion, 17th Regiment. Initially, elements of the Chinese 7th Division move silently toward the target and soon after, on the signal, they start the ascent on the first of many attacks. Successive waves pound against the American defenses. The outpost is hammered by a force of about company size, but the subsequent attacks continue to build in strength. Although vastly outnumbered, the defenders take a high toll on the enemy.

The troops peer down the slopes and suddenly see an ocean of Chinese. Heavy fire commences to knock out the initial wave, but the Chinese are more numerous than the amount of ammunition available. After the machine gun ammunition is expended, the troops revert to other weapons, including the bayonet. However, the sheer numbers of the enemy eventually force the Americans to pull back from the crest and regroup.

The south slope becomes the new line of defense for Company A, and soon after for Company B, which arrives to bolster the positions. Meanwhile, the Chinese, during the course of repeated assaults, gain ground on the north and west slopes and a large portion of the east slope. In the midst of the nasty weather, the grim darkness and near-insurmountable odds, the troops of Companies A and B launch counterattacks to match the determination of the relentless Chinese.

Despite disrupting the communications of the Americans and controlling the summit by the following day, the Chinese are unable to finish off the defiant defenders, who themselves hold an invaluable piece of the hill, the primary trench, and the key to preservation, the access road from the outpost to the rear and the 7th Division’s MLR.

On the morning of the 7th, the intense fighting continues; however, neither side can claim victory nor permanent progress. The attacks and counterattacks do not change the control of the hill. On the 8th, Companies E and G, 17th Infantry Regiment, relieve Companies A and B. Vicious fighting continues, but still, the battle remains fluid and neither side gains the advantage. Again, on the 9th, the U. S. 7th Division mounts unsuccessful attacks. Nevertheless, neither side is willing to concede.

The bloodbath continues into the following day, the 10th, when the Chinese mount yet another night attack in an attempt to gain total control of Hill 255. The pork chop-shaped elevation, by this time, becomes one more battle-scarred piece of earth that holds no great value, except the lives of those who have been lost to hold it. And, the contingents of the 17th and 34th Infantry Regiments that have been fighting to hold what they have, plus evict the Chinese, remain determined to regain the battered ground.

On the 10th, little remains on the hill that can be further destroyed, except the troops. The Communists continue to propel mortar shells into the American positions at a rapid pace. Company K, 32nd Infantry, arrives at Pork Chop Hill during the morning, but it had to pass through storms of artillery and mortar fire in order to relieve one of the other beleaguered units.

The Americans continue to hold the hill positions, but the Chinese form for a major assault during the morning hours of the 11th, when a battalion attacks the Americans. The superior numbers of the Chinese compel the Americans to give some ground; however, they remain steadfast in the collapsed trenches.

In the meantime, it becomes evident to the commanders that the Chinese are willing to spend as many lives as necessary to take the hill and that the strategic value is outweighed by the additional cost of American lives. It is decided to abandon the outpost, but with the Chinese able to observe the operations on Pork Chop from Old Baldy, the maneuver to withdraw could be extremely costly, particularly if it is initiated in the darkness.

In an attempt to fool the Chinese, it is decided to use the armored personnel carriers during daylight on the 11th to inconspicuously remove the defenders. The Chinese are familiar with the daily runs by the armor to bring up ammunition and supplies. The ruse works perfectly, as the Chinese are convinced that the armor had been bringing in supplies and reinforcements. Consequently, the hill is abandoned without incident, but prior to departure, the area is set with various booby traps. Nearly two days pass before the Chinese figure out what had occurred. Once they do, they move out to occupy the American positions to control the entire hill, only to be hit with devastating artillery fire that transforms the pocketed summit into what looks like a section of a level prairie.

During the final battle for Pork Chop Hill, General Trudeau, the 7th Division commander, led one of the counterattacks up the slopes. Two men, Corporal Dan D. Schoonover (Company A, 13th Engineering Bn.) and 1st Lt. Richard T. Shea, Jr. (Company A, 17th Infantry Regiment) become recipients of the Medal of Honor, posthumously. The Americans sustain just under 250 killed and more than 900 wounded. The Chinese sustain casualties estimated as high as about 6,000.

(Sometimes now there is confusion about who held Pork Chop Hill at the end of this final battle. The confusion is due to a motion picture titled Pork Chop Hill made in 1959. It showcased the grueling warfare during the battle to gain Pork Chop Hill; however, the picture was focused on a previous battle for the hill during April 1953.)