At the outset both sides were militarily weak. The North did have a clear advantage at sea, although its widely scattered force of 80 warships was totally inadequate for what lay ahead. On 19 April Lincoln proclaimed a blockade of the 3,500 miles of Confederate coastline. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles launched a major construction program, which included ironclads. Washington also purchased civilian ships of all types, many of them steamers, for blockade duty.

In April 1861, upon the secession of Virginia, the South gained control of the largest prewar U. S. Navy yard at Gosport (Norfolk) along with 1,200 heavy guns, valuable naval stores, and some vessels. Among the latter was the powerful modern steam frigate Merrimack. Set on fire by retreating Union forces, she burned only to the waterline before sinking. The Confederates raised her and rebuilt her as the ironclad Virginia. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory hoped to offset the Northern naval advantage by ironclad warships capable of breaking the blockade, and he advocated commerce raiding, the traditional course of action of a weaker naval power against a nation with a vulnerable merchant marine. Mallory hoped to drive up insurance costs, weaken Northern resolve, and force the U. S. Navy to shift warships from blockade duties

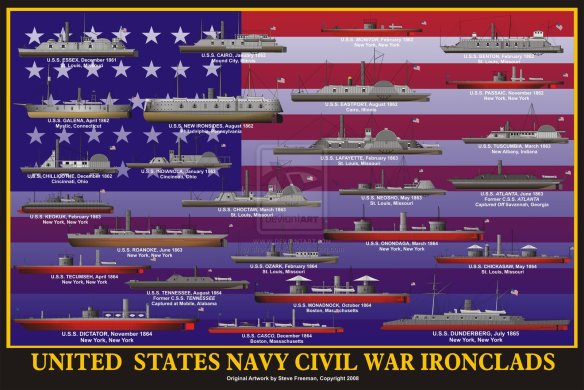

Each side also constructed ironclads. The first were actually built by the Union to help secure control of America’s great interior rivers. Thanks to its superior manufacturing resources, the Union got its river fleet built quickly. In August 1861 the army ordered seven ironclad gunboats. Constructed by James B. Eads, they were the first purpose-built ironclad warships in the Western Hemisphere.

The so-called Peninsula Campaign set up history’s first battle between ironclads. On 8 March 1862 the Confederate ironclad Virginia sortied from Norfolk and sank two Union warships. That evening the Union ironclad Monitor arrived, and the next day the two fought an inconclusive battle, which nonetheless left Union forces in control of Hampton Roads. “Monitor fever” now swept the North, which built more than 50 warships of this type. The Confederates countered with casemated vessels along the lines of the Virginia, the best known of these being the Arkansas, Manassas, Atlanta, Nashville, and Tennessee. Also, the Confederacy secretly contracted in Britain for two powerful seagoing ironclad ships. These so-called Laird Rams were turreted vessels superior to any U. S. Navy warship, but when the war shifted decisively in favor of the Union the British government took them over.

The distinction for participating in the first ironclad-to-ironclad clash must go to the Ericsson turret armorclad USS Monitor, the world’s first mastless ironclad. At the Battle of Hampton Roads (8 March 1862), Monitor faced off Confederate ironclad battery CSS Virginia in one of the very few naval battles fought before a large audience, lining the Virginia shore.

It is popularly supposed that Hampton Roads demonstrated that the day of the wooden warship had ended. It did no such thing; the armored Kinburn batteries had already taken the world’s attention almost six years before, the French La Gloire had been in service for the previous two years, and the magnificent seagoing British ironclad HMS Warrior for six months; and the world’s naval powers at the time had some 20 ironclads on the stocks. It would have been a peculiarly dense naval officer or designer who did not realize by March 1862 that ironclads would dominate the world’s fleets in the very near future. The main question would be what forms those ironclad warships would take.

The historic Battle of Hampton Roads did touch off a veritable monitor mania in the Union: Of the 84 ironclads constructed in the North throughout the Civil War, no less than 64 were of the monitor or turreted types. The first class of Union monitors were the 10 Catskills: Catskill, Camanche, Lehigh, Montauk, Nahant, Nantucket, Patapsco, Passaic, Sangamon, and Weehawken. (Camanche was shipped in knocked-down form to San Francisco. But the transporting vessel sank at the pier. Camanche was later salvaged, but the war was already over. Camanche thus has the distinction of being sunk before completion.) These ironclads, the first large armored warships to have more than two units built from the same plans, were awkwardly armed with one 11-inch and one 15-inch Dahlgren smoothbore. The Passaics were followed by the nine larger Canonicus class: Canonicus, Catawba (not completed in time for Union service), Mahopac, Manayunk, Manhattan, Oneonta, Saugus, Tecumseh, and Tippecanoe, distinguishable by their armament of two matching 15-inch smoothbores and the removal of the dangerous upper-deck overhang.

The eminent engineer James Eads designed four Milwaukee-class whaleback (sloping upper deck) double-turreted monitors: Chickasaw, Kickapoo, Milwaukee, and Winnebago. (Ericsson, on the other hand, loathed multiple-turret monitors, sarcastically comparing the arrangement to “two suns in the sky.”) Eads’s unique ironclads mounted two turrets, one of the Ericsson type (much to Ericsson’s disgust), the other of Eads’s own patented design: The guns’ recoil would actually drop the turret floor below the waterline for safe reloading; hydraulic power would then raise the floor back to the turret, wherein the guns could be run out by steam power. Eads’s two paddlewheel wooden-hull monitors, Osage and Neosho, designed for work on western rivers, were also unique. Although built to Eads’s designs, the two paddlewheel monitors mounted Ericsson turrets. All of the above monitors saw action in the U. S. Civil War. Completed too late for action were Marietta and Sandusky, iron-hulled river monitors constructed in Pittsburgh by the same firm that had built the U. S. Navy’s first iron ship, the paddle sloop USS Michigan.

Ericsson designed five supposedly oceangoing Union monitors: the iron-construction Dictator and Puritan, and the timber-built Agamenticus, Miantonomah, Monadnock, and Tonawanda.

The one-of-a-kind Union monitors were Roanoke, a cut-down wooden sloop; and Onondaga, also of timber-hull construction. Ozark, a wooden-hull light river monitor, had a higher freeboard than any Union monitor and also mounted a unique underwater gun of very questionable utility. None of the seagoing or the one-of-akind monitors saw combat.

Keokuk was an unlucky semimonitor (its two guns were mounted in two fixed armored towers and fired through three gun ports-a revolving turret would seem to have been an altogether simpler arrangement). The fatal flaw was in the armor, a respectable 5.75 inches, but it was alternated with wood. Participating in the U. S. Navy’s first attack on Charleston, South Carolina, Keokuk was riddled with some 90 Confederate shots and sank the next morning.

Aside from riverine/coastal ironclads, the Federals built only two broadside wooden ironclads, New Ironsides and Dunderberg (later Rochambeau, a super-New Ironsides, almost twice the former ironclad’s displacement), both with no particular design innovation. But New Ironsides could claim to be the most fired-upon ironclad during naval operations off Charleston, perhaps the most fired-upon warship of the nineteenth century, as well as the ironclad that, in turn, fired more rounds at the enemy than any other armored warship of the time. The broadside federal ironclad was formidably armed with fourteen 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbores and two 150-pound Parrott rifles, as well as a ram bow. Its standard 4.5-inch armor plate was far superior to the laminated plate of contemporary monitors. Whereas the monitors off Charleston suffered serious damage from Confederate batteries (and semimonitor Keokuk was sunk), New Ironsides could more or less brush off enemy projectiles and was put out of action only temporarily when attacked by a Confederate spar torpedo boat. During its unmatched 16-month tour of duty off Charleston, it proved a strong deterrent to any Confederate ironclad tempted to break the Union’s wooden blockading fleet off that port city, becoming the “guardian of the blockade.” Still, naval historians have tended to ignore New Ironsides and its wartime contributions because of the conservative design.

In light of their technological inferiority to British turret ironclads, it is difficult to understand why the Union’s Ericsson-turret monitors were also built by other countries: Brazil, Norway, Russia, and Sweden either built their own Ericsson-style monitors or had them built in other countries. (The Swedes, naturally enough, named their initial monitor John Ericsson.) The Russians constructed no less than ten Bronenosetz-class coast-defense monitors, and the Norwegians four similar Skorpionens. The Royal Navy ordered a class of four dwarf coastal ironclads that could be termed monitors, but they carried, of course, Coles turrets on breastworks well above the height at which they would have been mounted on Ericsson monitors, and they had superstructures. Furthermore, unlike the monitors, these coastal ironclads were in fact the diminutive template of the mastless turreted capital ship of the future.

The Union monitors, although an intriguing design, were in truth merely coastal and river warships; although several ventured onto the high seas, they only did so sealed up and unable to use their guns. Their extremely low freeboard (a long-armed man could have dipped his hand in the water from the deck) and tiny reserve of buoyancy made them liable to swamping, beginning with Monitor itself, which foundered off the North Carolina coast in December 1862. Monitor Tecumseh went down in less than two minutes after striking a mine at the Battle of Mobile Bay, the first instantaneous destruction of a warship, an all-too-common event in the twentieth century’s naval battles. Tecumseh was also the first ironclad to be sunk in battle, if one discounts two federal riverine armorclads sunk earlier at the Battle of Plumb Point Bend in May of 1862.

In fact, although the monitors might have been impervious to any Confederate gunnery, Southern mines destroyed the only three such warships sunk by the enemy: Patapsco, Tecumseh, and Milwaukee.(Monitor Weehawken foundered on a relatively calm sea in Charleston Harbor.)

The monitors also suffered from an extremely slow rate of fire; Monitor itself could get off only one shot about every seven minutes. Each shot required that the monitor’s turret revolve to where its floor ammunition hatch matched that of the hull; when firing, the two hatches were out of alignment to protect the magazine. And if an enemy shot hit where the turret met the upper deck, the turret could jam, something that apparently never happened to the many turrets built with Coles’s system.

In 1865, the U. S. Board of Ordnance obtusely argued that warships intended for sea service would be best with no armor at all. Yet at that very moment the Royal Navy had deployed five seagoing ironclads, including the magnificent pioneering Warrior and Black Prince, both warships with truly oceanic range, not to mention Defence, Resistance, and the timber-hull Royal Oak, Prince Consort, and Hector. The French, of course, years before had commissioned the seagoing La Gloire as well as Magenta and Solferino, the latter two the only ironclads ever to mount their main battery on double gun decks. (Magenta also has the melancholy distinction of being the first of the capital ships to be destroyed by mysterious explosion, a fate followed by about a score of such warships in the succeeding decades.)

In view of their design faults, plus their inferior and extremely slow firing guns and laminated armor, the monitors were a dead end in naval architecture from the start. The fact that Washington would consider the British sale of just two Coles turret rams to the Confederacy as grounds for war is a strong indication that the administration of President Abraham Lincoln realized the superiority of British-built turret ships to Union monitors.

Confederate Ironclads

Confederate secretary of the navy Stephen Mallory also wanted another type of ship for something far different from commerce raiding, one inspired by the old ship-of-the-line but possessed of some modern twists: an ironclad, steam-powered warship with rifled guns. He believed technological superiority would allow the South to overcome the disparity in numbers. “Such a vessel at this time could traverse the entire coast of the United States,” Mallory insisted, “prevent all blockades, and encounter, with a fair prospect of success, their entire navy.” They would allow the South to seize the naval initiative from its hidebound opponent. He eventually followed two routes to obtaining ironclads—buying them abroad and building them at home.

The Confederate Congress proved very receptive to Mallory’s ideas, voting $3 million to buy warships, including $2 million for ironclads. Mallory dispatched Lieutenant James North to Europe with instructions to try to buy a ship of the Gloire class, the innovative French ironclad commissioned in 1858. If this proved impossible, he should try to have one built. North, though, proved more interested in sightseeing than in doing his job. Mallory’s agents tried buying ironclads in Europe from May to July 1861, without success. The Confederate navy secretary decided to build them at home and signed deals for a few ships.26 Mallory also decided to build flotillas at various ports for their defense and gunboats for the Mississippi.

Building ironclads consumed most of the South’s naval effort. Mallory began studying the possibility of their construction in Southern yards in early June 1861. The first one arose from the burnt-out hulk of the USS Merrimack at Hampton Roads. The Confederacy had to do it this way because the South lacked the ability to build the ship it wanted from scratch. Mallory planned to use this new vessel, which became CSS Virginia, to clear the Union navy from Hampton Roads and Virginia’s ports. He generally believed that ironclad rams (which Virginia became) would be most useful for coastal defense. By late 1861, the Confederates had five ironclads in the works.

The Confederacy built ironclads to compensate for the enemy’s great numbers of warships. The South could not build oceangoing armored ships like Britain’s Warrior and France’s Gloire, but it could build slower, coastal ones like Virginia. These would, Mallory insisted, “enable us with a small number of vessels comparatively to keep our waters free from the enemy and ultimately to contest with them the possession of his own.” Mallory envisioned great but ultimately unrealistic achievements for Virginia. He believed that with a calm sea it could sail up the coast and attack New York City, causing such a panic that it would end the war. The Virginia’s success at Hampton Roads—ramming and sinking the USS Cumberland, then setting ablaze and driving aground the USS Congress—spurred Mallory to press the building of the CSS Louisiana in New Orleans, remarking that the “ship, if completed, would raise the blockade of every Gulf port in 10 days.”