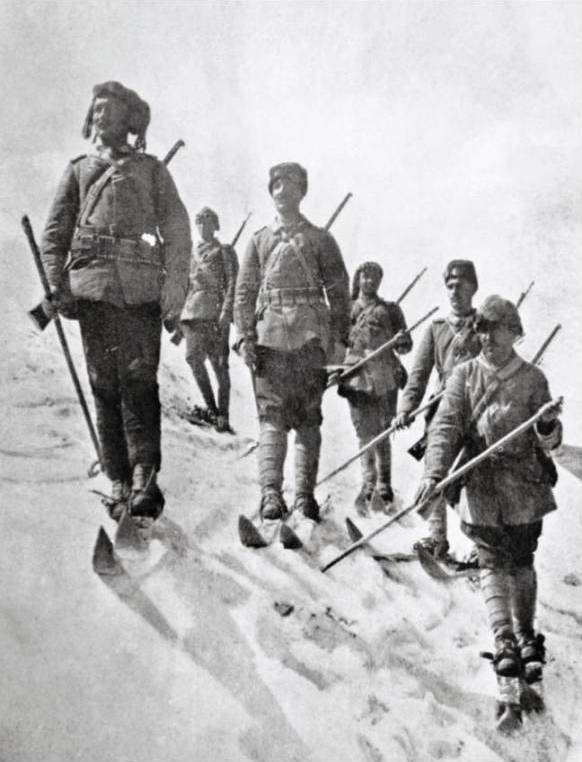

Ottoman 3rd Army winter gear

With the Ottoman assault on Sarikamish having stalled, General Yudenich, Chief of Staff of the Russian Caucasus Army, senses an opportunity to deliver a devastating counterattack. The Ottoman IX and X Corps at Sarikamish are dependent on a single line of communication back to Ottoman territory running through Bardiz, and Yudenich concludes that if the bulk of I Caucasian and II Turkestan Corps can hold the line against the Ottoman XI Corps, IX and X Corps can be encircled and annihilated. To this end, he has ordered two regiments from II Turkestan Corps at Yeniköy to move north towards Bardiz, and today they are able to bring the town under artillery fire.

For the past several days, the Ottoman X Corps has been moving south towards Sarikamish, but marching across mountain peaks and through waist-deep snow has seen it lose a third of its strength to the elements. When it arrives at Sarikamish today alongside IX Corps, the two units can muster only 18 000 soldiers to attack a Russian garrison that now numbers 14 000. Though the Ottomans manage to sever the rail connection between Sarikamish and Kars, and though elements of 17th Division break into the town after dark, the Russians are able to rally and repulse the enemy assault.

With the arrival of 17th Division today, Enver Pasha orders IX Corps to attack Sarikamish, even though X Corps has not yet arrived, and despite IX Corps having lost 15 000 of its starting 25 000 men over the past five days to the weather. Moreover, since December 25th the Russian garrison of Sarikamish has grown from two battalions of infantry to ten, and though the Ottomans press their attacks with great courage and tenacity, they are unable to break through the Russian lines and occupy the town.

In the Caucasus the occupation of Bardiz today by the Ottoman 29th Division of IX Corps masks growing problems with Enver’s offensive. Moving through heavy snow and in frigid conditions, thousands are already being lost to the elements; 17th Division of IX Corps reports that as much as 40% of its soldiers have fallen behind, some undoubtedly disappearing into the drifts of snow. X Corps to the north, meanwhile is exhausted, but two of its divisions are pushed northwards towards Ardahan before Enver orders it to redirect itself westwards to cover IX Corps left flank. 29th Division, meanwhile, is given no rest – Enver instructs it to march immediately on Sarikamish, not only to complete the envelopment of the Russian forces facing XI Corps but because the Ottoman units need to seize Russian supplies if they are not to run out of food and starve.

On the Russian side, I Caucasian and II Turkestan Corps are in the line facing XI Corps when Enver begins his offensive, the former to the south of the latter. The first response of General Bergmann, commander of I Caucasian Corps, had been to order his force to advance westward in an attempt to threaten the rear of the Ottoman IX and X Corps. General Nikolai Yudenich, Chief of Staff of the Russian Caucasus Army, is better able to understand the threat the Ottoman advance poses to Sarikamish, and orders I Caucasian Corps to instead withdraw today while moving reinforcements to concentrate at the threatened town.

What will become the Battle of Sarikamish begins today when Enver Pasha orders the Ottoman XI and X Corps of his 3rd Army to begin their advance into the Russian Caucasus. Enver’s objective is the town of Sarikamish, which sits at the head of the main railway supplying Russian forces in the Caucasus, but his plan bears the strong imprint of German thinking and the influence of 3rd Army’s Chief of Staff Baron Bronsart von Schellendorff. Of 3rd Army’s three corps, XI Corps, reinforced by two divisions that had been originally bound for Syria and Iraq, was to frontally attack the two Russian corps southwest of Sarikamish in order to fix them in place. This was no small task for XI Corps, given the two Russian corps number 54 000 men and the Ottoman unit would have been outnumbered by just one of the enemy corps. The key maneouvre, however, is to be undertaken by IX and X Corps. The former, sitting on XI Corps’ left, is to advance along a mountain path known as the top yol towards Çatak, from which it can descend on Sarikamish from the northwest, outflanking the two Russian corps pinned by XI Corps. Though the top yol is known to the Russians, they believe it was impractical to move large bodies of troops along it. Enver, for his part, believes that not only is the path useable but its high altitude and exposed position would ensure that high winds kept it swept of snow, as compared to the valleys below. Finally, X Corps, on the left of IX Corps, is to advance and occupy the town of Oltu, from which one portion of the corps can move to support IX Corps’ move on Sarikamish, while another portion can continue northeastwards towards the town of Ardahan. If successful, the plan promises the envelopment and annihilation of the two Russian corps southwest of Sarikamish and the opening of the way to Kars.

With its emphasis on outflanking the enemy position, it has the obvious imprint of the thinking of Schliffen and the German General Staff. Further, Enver’s plan involves precise timetabling of the advance of IX and X Corps (necessary given the lack of communications between the three corps of 3rd Army) which removes all possibility of improvisation and does not allow for any unit to fall behind schedule. Finally, there is the emphasis on speed – the soldiers of IX Corps, for instance, are told to leave their coats and packs behind to quicken their advance. This ignores the obvious reality of conducting operations in the Caucasus in December and January – temperatures are consistently below -30 degrees centigrade and the snow on the ground is measured in feet, not inches. This ignorance of the human element, also a conspicuous reflection of pre-war German planning, is to be of decisive import in the days ahead.

By choosing to enter the war on Germany’s side, the Ottomans were tying the fate of their empire to Germany’s. It was a calculated risk. Germany stood an excellent chance of winning the war, and it had no immediate designs on Ottoman territory. Its victory would provide the outcome most conducive to affording the breather they needed to implement the reforms to rejuvenate their empire. From the German perspective, the Ottoman empire could fulfill three functions. It could cut Russia’s communications through the Black Sea to the rest of the world, tie down Russian forces in the Caucasus, and “awaken the fanaticism of Islam” to spark rebellions against British and Russian rule in India, Egypt, and the Caucasus.

Around the time of the signing of the secret alliance, Enver and the Germans had discussed a number of speculative war plans, most involving offensives in the Balkans. In the middle of August Enver ordered his German chief of staff to draw up a formal plan for the opening of the war. The plan identified the main axis of effort to be an attack on the Suez to cut British communications to India and left open the option of an amphibious landing in the vicinity of Odessa. Another possibility the plan offered was a joint offensive against Serbia and Russia in the Balkans. Throughout the opening months of the war Ottoman and German planners remained committed to a passive stance in the Caucasus. Indeed, the August mobilization deployed the bulk of the Ottoman army in the west in Thrace, not in the east. The Ottoman force facing the Caucasus, the Third Army, was to brace for an attack and mount a defense around Erzurum. Only in the event of a decisive defeat of the Russians was the Ottoman army to go on the offensive.

When Russian forces began to close in on the Austro-Hungarian city of Lemberg (Lviv), Vienna urged the Ottomans to launch an amphibious invasion near Odessa to relieve the pressure. The initial enthusiasm for the idea of Enver and Austrian and German planners, who entertained ideas of inciting not just Muslims but Georgians, Jews, and even Cossacks to rebel against the Russians, faded once the enormous logistical difficulties involved became clear. They did not give up the idea of an amphibious operation altogether. Major Süleyman Askerî Bey, the chief of the Tekilât-ι Mahsusa, envisioned smaller clandestine landings of Ukrainian and other partisans along the Black Sea coast to spark rebellions.

The Tekilât-ι Mahsusa and the Program of Revolution

Enver Pasha had founded the Tekilât-ι Mahsusa in November 1913.59 The experience of fighting against insurgents in the Balkans and as an insurgent against the Italians had impressed upon Enver and other officers the utility of an organization for irregular warfare. Moreover, an organization that could act in secrecy and lend the Ottoman state “plausible deniability” had obvious utility in the cutthroat yet diplomatically bounded international environment in which the Ottomans were forced to maneuver. Enver and his German advisors hoped to use the Tekilât-ι Mahsusa to spark uprisings behind the lines of their foes. In August Tekilât-ι Mahsusa operatives formed units in Trabzon, Van, and Erzurum to carry out clandestine and guerrilla operations inside Russia and Iran. Bahaeddin akir took command of the unit in Erzurum, the Caucasus Revolutionary Committee. The committee recruited heavily among Circassians. For purposes of internal security and secrecy, it required two current members to attest to a candidate’s trustworthiness. By mid September they had formed several bands of Circassians and Iranians armed with pamphlets as well as small arms and grenades. Addressed to “our brothers in faith,” the appeals of the Caucasus Revolutionary Committee called upon the Muslims of the Caucasus to rise up against the “Moskof” oppressor and to drive the “unbeliever” from the Caucasus entirely. Several operatives left for the North Caucasus and Azerbaijan, where they made contact with locals, including Mehmed Emin Resulzade of the Musavat Party.

The Kaiser was not the sole German holding high hopes for the revolutionary possibilities of pan-Islam. Extrapolating from the conviction that Islam was a martial religion that could not countenance the rule of unbelievers over Muslims, German policymakers presumed that Muslims under Entente rule were essentially obliged by both belief and psychological constitution to revolt. With much encouragement from them, Ali Haydar Efendi, the Ottoman sheikh ul-Islam – the most senior religious authority in the Ottoman state – proclaimed a jihad on 14 November, three days after the Porte’s declaration of war. The proclamation summoned all Muslims, Shii as well as Sunni, to war against Russia, Britain, and France. The call to jihad had little to no effect, except perhaps among the Kurds of Iran, among whom more immediate factors were at work. The idea of waging a holy war in alliance with the infidel powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary was dubious at best. Rumors that Germany had paid for the proclamation circulated inside even the Ottoman empire. Most Muslims did not find that their own circumstances merited war, regardless of what a religious scholar in Istanbul might declare.

The Germans’ ardor for pan-Islam loomed greater than their competence or common sense, and they often worked at cross-purposes with their Muslim Ottoman allies, who viewed German efforts in the Middle East with suspicion. The presence in the German effort of unqualified specialists and outright charlatans did not improve matters. The German Foreign Ministry hired a journalist, Max Froloff, to go to the Red Sea region to recruit Muslim holy warriors. Froloff opted to make a shorter trip to Holland where he wrote an account of his imagined experiences. The publication of his book nonetheless had an impact. Its descriptions of Froloff’s visits to Mecca and Medina, holy cities strictly barred to non-Muslims, sullied the Ottomans’ reputation as guardians of the sacred sites and consequently incensed them. Another German project bordering on the surreal was the dispatching, over the objections of Enver and the Ottoman Interior Ministry, of an Austrian orientalist and Catholic priest, Alois Musil, to inspire Muslim Arabs to embark on jihad. Notably, after returning from Arabia, Musil testified to the “complete indifference of the tribes toward holy war and Pan-Islamic ideas.” The belief that the Germans were using such missions to prepare the ground for the postwar expansion of German influence haunted the Ottomans, who obstructed German efforts at holy war at several junctures. Frustrated, the Germans moved the center of pan-Islamic operations in 1916 from Istanbul to Berlin.

Perhaps precisely because they themselves were Muslims, many Ottoman officials had been skeptical about the possibilities of pan-Islamic revolution from the beginning. Consular officers in Taganrog, Odessa, Novorossiisk, Batumi, and Tiflis all reported that Russia’s mobilization had only caused people, including Muslims, to rally around the tsar. In Tiflis Muslims were praying for Russia’s victory. The chargé d’affaires in St. Petersburg Fahreddin Bey predicted that in the event of war the vast majority of Russia’s Muslims would not only fail to take active measures on the Ottomans’ behalf but would probably fight alongside the Russians as in the War of 1877–78. Most were living in poverty and uneducated, he explained, and those with some education tended to be even more pro-Russian. Indeed, Enver himself advised his subordinates that most of Russia’s Muslim Circassians would fight on Russia’s side and that the “Türkmen” (by which he probably meant Azeri Turks) and Muslim and Christian Georgians would merely refrain from actively supporting Russia.

The war opens

Before their respective governments had declared war, Russian and British armed forces initiated combat operations against the Ottomans along the Iranian border, in the Persian Gulf, and in the Levant. Russia’s initial war plan for the Caucasus provided for an active defense with limited local offensives. Encountering only light resistance, however, Russian forces from Iran pushed further into Ottoman territory to occupy Köprüköy and threaten Erzurum. The Ottoman army then struck, however, and within two weeks had driven their foes back. To the north, where the Tekilât-ι Mahsusa raised a force of some 5,000 Laz and Ajar irregulars, Ottoman forces managed to take the towns of Artvin and Ardanuch. They announced their entrance into the formerly Ottoman town of Ardahan toward the end of December by firing off a telegram to Istanbul boasting simply, “Greetings from Ardahan!” These victories had not been easy, and rifts between the Tekilât-ι Mahsusa and regular army led Enver to dismiss Bahaeddin akir from command, but in the initial confrontations the Ottomans had bested the Russian Caucasus Army.

Sarikamish: gamble and disaster

These early successes emboldened Enver to plan a major offensive to envelop and crush Russian units in the vicinity of Sarikamish (Sarιkamι). In view of the rugged terrain, the winter weather, and the balance of forces, the plan involved tremendous risks, which Enver’s subordinates brought to his attention. Enver, however, was not one to fear risk. His meteoric rise had taught him to embrace it. The hero of 1908 had gone from junior officer to minister of war in a mere five years. Moreover, his German chief of staff, Bronsart von Schellendorf, was encouraging him to undertake a major offensive. With Germany’s armies bogged down on two fronts and Austria-Hungary on the defensive, the short victorious war the Central Powers had wagered on was growing into a stalemate. If the Ottomans could envelop the Russians on the Caucasian front and inflict a stunning defeat on them as the Germans had done at Tannenberg, the war effort would regain momentum. Enver had no experience commanding large units but, ever self-confident, he arrived in Erzurum to take personal command of the operation.

The offensive commenced on 22 December. Unseasonably warm weather boded well. In the initial days the 95,000-strong Third Army made good progress. By coincidence, the tsar had appeared in Sarikamish on a morale-building mission, and some Russians now feared the advancing Ottomans might capture him. The population in Sarikamish and even some Russian generals panicked. But in the meantime the weather shifted dramatically. Temperatures plunged to −36°C and blizzard conditions set in, trapping tens of thousands of poorly clothed Ottoman soldiers in the mountain passes. Most of these were without winter gear and some were without even footwear. Meanwhile, newly arrived reserves enabled the Russians to counterattack. The result was a calamitous rout from which the Ottoman army would never fully recover. Not until 1918 and the disintegration of the Russian army would the Ottomans again be able to go on the strategic offensive on the Caucasian front.

As bad as it was, the disaster of Sarikamish later acquired mythical proportions as part of an effort to discredit the Unionists and Enver in particular. Thus Enver’s decision to launch a wintertime offensive with ill-clothed troops in the mountains is often presented as the epitome of stupidity and fanaticism. Total Ottoman losses were crippling, but closer to 60,000 than the 130,000–140,000 of popular legend. One explanation advanced for Enver’s otherwise seemingly ineffable heedlessness for entering both the war and the offensive at Sarikamish is a deep-seated pan-Turanism, a grand desire to unite the Turkic and Muslim peoples of the Caucasus, Russia, and Central Asia with those of the Ottoman empire. Such an explanation is not convincing. As noted earlier, Ottoman mobilization plans deployed the army in the west, not on the Caucasian front. Despite the fact that an invasion of the Caucasus was the most obvious and straightforward way to bring the war to Russia, Enver settled on a Caucasian offensive only after discarding for geographic and logistical reasons other options of attack through the Balkans or across the Black Sea. The military stalemate in Europe led Germany and Austria-Hungary to press the Ottomans to launch an offensive against Russia sooner. Enver’s concept of encircling Russian units at Sarikamish and cutting them off from their rear was daring but not hare-brained, and in accord with standard military doctrine. Finally, the Ottomans made no effort even to present the operation as pan-Turanist. Liman von Sanders does recollect that Enver commented that he “contemplated marching through Afghanistan to India.” A conversational aside is hardly conclusive evidence, and it is notable that Enver stated the objective was India. India was not an objective of pan-Turanism, but British India had long been an objective of Britain’s rivals, including Germany and Russia.

Given that the advice of Enver’s Ottoman and German staff officers alike was split regarding the proposed operation, Enver’s personality became critical to the decision to attack. Personal experience had taught the youthful war minister that boldness pays. The Third Army executed the first half of the operation well, but the drastic shift in the weather and the uncommonly swift Russian counterattack sealed its fate; its fate was not sealed from the beginning. The tactical blunder committed by Enver at Sarikamish – emphasized so often to underscore the alleged irrational pull of pan-Turanism upon Enver and the Ottomans in general – is less remarkable when compared with the record of British, French, and German generals fighting on the western front in France, who sacrificed far greater numbers of lives over a longer period of time for no strategic advantage.

Shortly after it had commenced its offensive on Sarikamish, the Ottoman army launched a probe into northern Iran. The idea was that a relatively small force led by the Unionist and Tekilât-ι Mahsusa commander Ömer Naci Bey, who had fought alongside Iranian constitutionalists in 1907 and knew the region, would rally the Muslims of Iran to rebel against the Russians, stir problems in the Russian rear, and perhaps even facilitate a drive toward Baku, the center of Russia’s oil industry. The probe initially made rapid headway when General Aleksandr Myshlaevskii, panicked by the advance at Sarikamish, ordered the abandonment of Urmia and Tabriz. The Russians’ sudden withdrawal inspired the Kurds of Iran, including the Russians’ erstwhile ally Simko, to swell the ranks of the Ottoman force. The Ottomans and their local allies entered Tabriz on 14 January, looting and wreaking terror upon Assyrian and Armenian villagers along the way. After Russian defenses at Sarikamish had stabilized, however, the chief of staff of the Caucasus Army General Nikolai Yudenich ordered General Fedor Chernozubov immediately to retake Tabriz and secure the northern Iranian plateau. The return of the Russians in force caused the Ottoman offensive in Iran promptly to collapse.

Attack on the Suez

At the same time that Enver was presiding over the disaster at Sarikamish, Cemal Pasha was readying forces for an offensive on the Suez. The offensive aimed at cutting Britain’s lines of communication to India and inciting the Muslims of Egypt and North Africa to rebel against their British and French overlords. Berlin assigned tremendous importance to attacking the British in Egypt and from the beginning of the war had been eager for an attack across the Suez Canal. The Ottomans had not foreseen a multifront war in which Britain was an adversary and so formed a new army, the Fourth, with its headquarters in Damascus. Cemal arrived on 18 November to take command of the offensive. Due to the long distances involved and the poor state of the roads and communications his army was ready only in the middle of January. The Ottoman and German planners hoped to exploit religious sentiment against the British and included in the 4th Army a number of imams for this purpose. A German advisor made the fantastic prediction that 70,000 “Arab nomads” would join their invading Ottoman co-religionists when they reached the canal. The inclusion of a company of Druze, a sect whose beliefs are anathema to mainstream Sunni Islam, however, belies the notion that Sunni fanaticism inspired the offensive.

After skillfully executing a difficult advance across the Sinai to the Suez, the 4th Army launched their attack across the canal on the night of 2 February. Although they achieved tactical surprise, they ran into difficulties at the canal due to improper equipment and a lack of training in water crossings. The British on the opposite bank rushed in reinforcements and repelled those who had made it across. After two days of fighting, Cemal pulled back, having suffered roughly 1,300 casualties.

The offensive had failed in part because Berlin pressured the Ottomans to attack prematurely. Nonetheless, it is doubtful that the offensive would have achieved major results even if the initial assault force had established a bridgehead on the western bank. Ottoman supply lines were long, Ottoman forces limited, and British military and naval power in and around Egypt was substantial. The outbreak of a rebellion in the British rear perhaps could have assisted the assault, but precisely to preclude such a possibility the British had withdrawn their native Egyptian troops to Sudan and deployed British and Indian troops to the canal. Because the Suez offensive resembled the Sarikamish operation in its timing, ambition, and mismatch between objectives and available resources, historians have tended to locate its origins, too, in an emerging ideology of pan-Islam. They overlook the Central Powers’ common interest in cutting British lines of communication and the Ottomans’ particular interest in expelling the British from Egypt, a land to which they had strong historical and cultural ties, and which had formally remained part of their empire until the outbreak of the war. The scale of defeat at the Suez was nothing like that at Sarikamish. The Germans, in fact, were satisfied with the operation despite its collapse because it had compelled the British to retain in Egypt troops they could have deployed to Europe.

The crushing defeat of Sarikamish and the failure at Suez deprived the Ottoman army of any offensive capability at the strategic level. The spring 1915 Anglo-French amphibious assault at Gallipoli, British thrusts into Mesopotamia and Palestine, and the steady advance of the Russian army across Anatolia would keep the Ottomans hard-pressed throughout the next two years. They would manage only limited counteroffensives in Anatolia and Mesopotamia, while also contributing substantial forces to joint operations in the Balkans. Deprived of an army and resources, pan-Islam, too, lost whatever strategic significance it may have possessed. In Iran, the Ottomans, backed by the Germans, made appeals to Muslims to join them in the struggle against the infidel Russians and British, but the larger legions and greater resources of the Entente proved to be more persuasive stimuli for the Muslims of Iran. Following their defeats there was little the Ottomans could do beyond backing the activities of a few individuals, such as Enver’s younger brother Nuri Pasha, who assisted the Sanussi tribesmen’s resistance to the Italians in Tripoli.91 The fact that pan-Islam exerted little pull on Muslims outside the reach of Ottoman or German material support is not insignificant, as it highlights yet again the ideology’s slight power.