In March 1860, exile Rosolino Pilo exhorted Giuseppe Garibaldi to take charge of an expedition to liberate Southern Italy from Bourbon rule. At first, Garibaldi was against it, but eventually agreed. By May 1860, Garibaldi had collected 1,089 volunteers for his expedition to Sicily.

Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had learnt revolutionary guerrilla tactics while fighting to liberate South America before returning to his fatherland. At the lowest ebb of his fortunes, was expelled from Piedmont-Sardinia and was forced to lead the life of an exile once more. He worked briefly as a candle-maker in Camden, New Jersey, before returning to Europe in 1854. He established himself in a house on the Sardinian Island of Caprera and gradually became more politically realistic. Under Camillo Benso di Cavour’s influence, Garibaldi accepted that the Piedmontese monarchy offered the best hope of unifying Italy. This renunciation of his Mazzinian and revolutionary principles restored him to favor in Turin, and in 1859 Garibaldi was made a general in the Piedmontese army.

Garibaldi was violently critical of the Treaty of Villafranca. In January 1860, he endorsed the latest venture launched by Giuseppe Mazzini, the “Action party,” which openly espoused a policy of liberating southern Italy, Rome, and Venice by military means. To this end, in the spring of 1860, Garibaldi led a corps of red-shirted patriots from Genoa to the assistance of a Mazzinian uprising in Palermo. The “Expedition of the Thousand” is the most famous of all Garibaldi’s military exploits. After landing near Palermo with the support of ships from the British fleet, Garibaldi swiftly took command of the island. On 14 May 1860, he became dictator of Sicily and head of a provisional government that was largely dominated by a native Sicilian who would play an important role in the political future of Italy, Francesco Crispi.

Garibaldi’s legendary Expedition of the Thousand that sailed from Piedmontese territory in May 1860 in support of the Sicilian insurgents presented Cavour with the most serious challenge of his political career. He opposed the expedition, but did not dare prevent it for fear of offending patriotic sentiment, losing control of parliament, antagonizing the popular Garibaldi, and crossing Victor Emmanuel, whom Cavour suspected of secretly backing Garibaldi. The government therefore adopted an ambiguous policy that allowed volunteers to sail for Sicily and avoid interception at sea. Garibaldi’s unexpected battlefield victories changed Cavour’s mind: he allowed reinforcements to go to Sicily, but also tried, unsuccessfully, to wrest control of the island from Garibaldi to prevent him from invading the mainland. When his attempt failed and Garibaldi marched triumphantly into Naples, Cavour sent the Piedmontese army to finish the fight against the Neapolitans, and to disarm and disband Garibaldi’s. The papal territory that the Piedmontese army occupied on its way to Naples was added to the rest of the booty and became part of the Kingdom of Italy that was formally proclaimed on 17 March 1861.

The Campaign

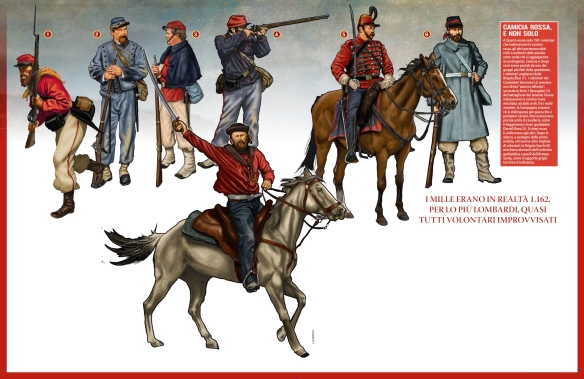

In one of the most dramatic moments of Italy’s unification, the revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi led an army of over 1,000 guerrillas to support a revolt in Sicily against their Neapolitan ruler, Francis II. While Garibaldi was a seasoned general of proven ability, the odds were stacked against him. His army – known as the Redshirts – was made of mostly untrained young idealists armed with rusty rifles. Meanwhile, Francis II boasted more than 20,000 highly skilled troops. However, the scarlet fighters quickly took the town of Marsala when they landed on Sicily’s west coast. As they made their way to Palermo, hundreds of Sicilian rebels joined them. The Redshirts won further Sicilian support after Garibaldi had the Neapolitan troops running scared at Calatfimi. By July, they had seized nearly all of Sicily and by September, crossed the water and captured Naples itself. Though Garibaldi’s efforts to march on Rome were checked, his ally King Victor Emmanuel II invaded the Papal States. Following a plebiscite, Garibaldi surrendered all of Sicily and Naples to Victor Emmanuel.

4 April 1860

Hearing that a revolt has broken out in Sicily, Garibaldi decides to attack the Bourbon regime.

5 May 1860

Garibaldi recruits more than 1,000 northern men for his expedition to Sicily. Their ships land at the port of Marsala a week later.

15 May – 20 July 1860

Over the next two months, the Redshirts win a series of victories over the Neapolitan forces at Calataimi and Palermo and capture the island.

7 September 1860

Garibaldi triumphantly enters Naples, where he is greeted as a hero by huge crowds. King Francis II led before the liberator arrived, heading by sea to Gaeta.

1 October 1860

King Francis II makes a final stand against Garibaldi at the Battle of Volturno, but Piedmontese troops arrive to support the Redshirts.

26 October 1860

Garibaldi meets Victor Emmanuel II at Teano and hands him control of the region. By March 1861, the Kingdom of Italy is finally established.

Giuseppe Garibaldi was marching north from Naples when he was attacked in a strong position at the Volturno, outside Capua, by the Neapolitan army of Francis II under General Giosue Ritucci. Aided by Piedmontese, fresh from victory at Castelfidardo, Garibaldi drove off the Bourbon forces with heavy losses on both sides. He then captured Capua and advanced on Gaeta (1-2 October 1860).

Battle of the Volturno, 1 October 1860

Giuseppe Garibaldi was marching north from Naples when he was attacked in a strong position at the Volturno, outside Capua, by the Neapolitan army of Francis II under General Giosue Ritucci. Aided by Piedmontese, fresh from victory at Castelfidardo, Garibaldi drove off the Bourbon forces with heavy losses on both sides. He then captured Capua and advanced on Gaeta (1-2 October 1860).

The Army of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was divided among the large garrisons of Gaeta, Capua, and Messina and the field army of 25,000 men. The Neapolitan Army held a strong position on the Volturno. Two infantry and one cavalry division camped outside Capua, with a third infantry division spread upstream holding the fords and bridges across the river. Garibaldi’s army had advanced to positions from Santa Maria to Caserta and Maddaloni a week earlier. His army now boasted 22,000 men divided among four divisions. Most of these men had served in Sicily, now supplemented by more volunteers.

Garibaldi despised positional warfare. The skirmishing between the armies had agitated the general. He determined to pin the Neapolitan Army under the walls of Capua, while crossing the Volturno and cutting off the king at Gaeta from his army. Simultaneously, the Neapolitan generals concurred that Garibaldi had placed his army in a precarious position between the divisions at Capua and the brigades of Mechel and Ruiz at Dugenta. They saw an opportunity to destroy Garibaldi’s forces by conducting a double-envelopment of the Southern Army.

On October 1 the armies moved in chorus. The Neapolitans struck first. Before 6am, General Anfan de Rivera’s division attacked Giacomo Medici’s 17th Division at Sant’Angelo. To the south, General Tabacchi’s and General Ruggeri’s divisions advanced on the 16th Division under General Milbiz at Santa Maria. Mechel’s brigade pushed in the lead battalions of Bixio’s 18th Division northeast of Maddaloni.

From Caserta Garibaldi was able to dispense the reserve to either flank. Garibaldi properly assessed the threat to his left, and moved reinforcements to support Milbiz and Medici. He went to Santa Maria in person, leaving Türr with the 15th Division at Caserta. On the right, some of Mechel’s battalions lost their way during their march on Maddaloni. This allowed Bixio to concentrate his forces and repel the initial attacks. Fighting raged throughout the day, but by 2pm Medici and Milbiz had determined that the Neapolitans were spent, and issued a counterattack. The renewed vigor of the Garibaldini forced the Neapolitans back to Capua. The success came just in time, as Ruiz’s brigade moved directly upon Caserta. Türr held the town until Medici sent aid. On the far right, Mechel’s uncoordinated attacks stalled, and he withdrew by the late afternoon.

Garibaldi narrowly won the battle of Volturno. He lost 2,000 killed, wounded, and prisoner, while the Neapolitans suffered 3,000 casualties and prisoners. The day after the battle, the Savoia Brigade of the Piedmontese army landed by sea north of Capua. Over the next several weeks Della Rocca’s V Corps crossed the Neapolitan frontier, followed by the rest of the Piedmontese Army. The Southern Army placed Capua under siege, and Piedmontese forces marched on Gaeta where the erstwhile Neapolitan king had taken refuge.