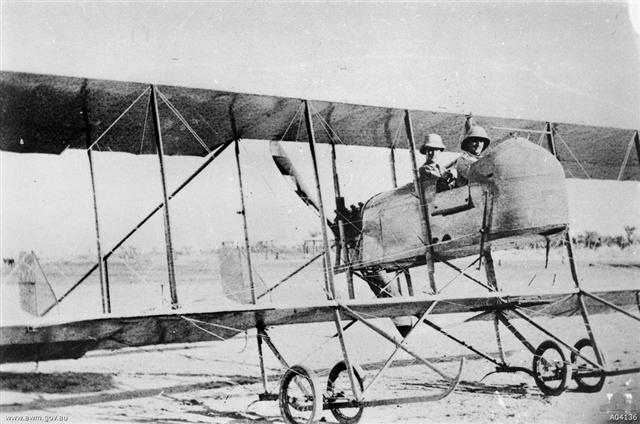

Maurice Farman Shorthorn of the Mesopotamia Half Flight in 1916 (Photo Source: Australian War Memorial)

By David Wilson

On 8 February 1915, the Government of India sought the assistance of Australia to supply trained airmen, aircraft and transport for service in Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Australian Government replied that men and transport would be provided, but that aircraft could not. The unit (known as the Mesopotamian Half-Flight, Royal Flying Corps) was quickly raised from senior non-commissioned officers serving at the Central Flying School and from volunteer trainee riggers and mechanics from the staff of the motor-engineering shops at the army depot at Broadmeadows. Captain Petre, the commander of the force, departed for Bombay on 14 April to make arrangements for the Half-Flight’s arrival, leaving Captain T.W. White in temporary command. White, Lieutenant W.H. Treloar, an officer from the 72nd Infantry Battalion who had learned to fly in England before the war, and 37 men departed from Melbourne aboard the Morea for Bombay six days later. The premonsoonal heat, oppressive to Australians used to moderate climates, engendered in them an unquenchable thirst. The culture and sights of Bombay took a toll on the Australians’ three months’ advance pay before they boarded the SS Bankura. The vessel was bound for the town of Basra on the Shatt el Arab, downstream from the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in south-eastern Mesopotamia.

The Australians arrived at Basra on 26 May, joining two Indian Army officers, Captains P.W.L. Broke-Smith and H.L. Reilly, and nine mechanics from the Indian Flying Corps. A New Zealander, Lieutenant W.W.A. Burn, completed the Dominion nature of the Half-Flight.

An Indian Army pioneer unit had completed a road made of date palm logs from the waterway to an Arab cemetery, the only high ground in the area suitable for an airfield. The surrounding swampland was a breeding ground for mosquitoes, forcing the troops to take quinine twice daily to counter the insidious effects of malaria. The novelty of Basra, its culture unchanged from biblical days, was a marked contrast to the Australian lifestyle. The clay buildings offered little relief for the Half-Flight members toiling in the oppressive summer heat to prepare the aircraft for operations.

Even by the standards of 1915, the aircraft initially supplied to the Half-Flight were not modern. With two Maurice Farman Shorthorn and a single Longhorn aircraft, with a maximum speed of 80 kph on a calm day, the Half-Flight was ordered to fly reconnaissance missions in support of the advance of forces under the command of Major General C.V.F Townshend along the Tigris River to Amara. Operations commenced on 31 May when two crews (Petre and Burn, and Reilly and Broke-Smith) flew from a landing ground south of Kurna and supplied useful intelligence to the force commander. Below them, the infantry force advanced upstream through the saturated landscape by using 500 Arab war canoes, supported by artillery mounted on barges and steamers. They succeeded in forcing the defending Turks to retreat. White and Reilly, who had battled a dust storm for two hours to fly the Shorthorn the 100 kilometres from Basra on 1 June, reported the fact to navy authorities. En route, the airmen attempted to drop three 20-pound bombs on one of the Turkish paddle steamers that was retreating in disarray. Although the bombs missed the intended target, they exploded ahead and astern of one of the smaller ships, the crew of which, having interpreted this action as the aerial equivalent to a naval ‘shot across the bows’, drew into shallow water where they waited and later surrendered to the first British vessel that appeared. Townshend took advantage of the Turkish confusion and, in company with Captain W. Nunn, Royal Navy, and 22 men, accepted the surrender of Amara in the early hours of 3 June.

To guard the left flank of the advance up the Tigris River toward Kut, a force was drawn from the 6th and 12th Divisions to capture Nasiriyah, on the Euphrates River. Reilly, Treloar, Petre and Burn were again instrumental in the capture of this township. They flew Caudron aircraft that had been ordered forward from Basra over the Euphrates marshes. The capture of Nasiriyah paved the way for the advance on Kut.

Although more suitable for training than active service, the Caudron was an improvement on the Shorthorn and Longhorn aircraft. Despite the construction of a brick engine-overhaul workshop (augmented by the repair-shop lorries that had been supplied from Australia) and an iron hangar at Basra that improved maintenance facilities, the unreliability of the aircraft engines had fateful repercussions. During the first reconnaissance flights towards Nasiriyah, Reilly had force landed in the floodwaters near Suk-esh-Sheyukh, where, with the assistance of the garrison, he was able to save the aircraft. Reilly and Merz planned to fly their aircraft back to Basra in company on 30 July to try to overcome engine problems. But the two aircraft became separated, with Reilly and his mechanic being forced to land 40 kilometres from a refilling station established at the island of Abu Salibiq. Merz and his companion, Burn, pressed on alone. They were never seen again.

Eyewitness evidence suggested that Merz and Burn had landed 35 kilometres from Abu Salibiq, where a well-armed force of Arabs attacked them. The two Australians attempted to retreat to Abu Salibiq, using their revolvers in a spirited defence, killing one and wounding five of the Arab assailants, before one of the Australians was wounded. Gallantly, the two officers fought together until the end, showing great personal commitment and devotion to each other. Search parties, sent out from Basra and Abu Salibiq, found that the Caudron had been reduced to matchwood, but discovered no sign of Merz or Burn.

Engine failure was a common occurrence for the Half-Flight with, as will be seen, dramatic and tragic ramifications. For the members of the Half-Flight it was a period of frustration, with tent hangars being destroyed by the ubiquitous hot, sandy winds, leaving frail aircraft subject to the vagaries of an insatiable climate. Moreover, the poor standard of workmanship at the maintenance facilities in Egypt and England meant that the engines required considerable upkeep. And yet it was also a period of innovation—to enable the Half-Flight to operate in the watery maze of the Mesopotamian river system two barges were constructed: one on which two aircraft could be transported and the second to serve as a floating workshop. Given the terrain, floatplanes would have been an asset, but attempts to modify one of the Maurice Farman aircraft to fly with floats proved unsuccessful. In August the nucleus of a seaplane flight, under the command of Major R. Gordon, was transferred from East Africa and proved its worth in the reconnaissance before and after the attack on Kut.

Four Martinsyde single-seat scouts also reinforced the unit, now known as 30 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC), in August. The first of these aircraft was test flown by Petre on 29 August, who found the performance of the aircraft a disappointment—it took the aircraft 23 minutes to reach an altitude of 2000 metres, and the maximum speed of 80 kph was only a marginal improvement on the Maurice Farman and Caudron types that it supplemented.

Early in September, 30 Squadron concentrated at Ali Gharbi, halfway between Amara and Kut. The squadron, due to aircraft unserviceability, could only deploy a single Maurice Farman, a single Caudron and two Martinsydes to support the Indian 6th Division’s attack on Kut. However, a series of accidents, and the capture of Treloar and Captain B.S. Atkins of the Indian Army after they suffered an engine failure while reconnoitring Es-Sinn on 16 September, reduced the aircraft strength to a single Martinsyde. To reinforce the aerial component four aircraft (all that were available) were ordered upriver from Basra on two seaplane barges. One Maurice Farman was damaged on an overhanging tree after a strong wind blew the barges into the riverbank. This aircraft was repaired in time for battle where, based at Nakhilat, it joined a Martinsyde to participate in the attack on Es-Sinn.

Commencing on 27 September, Townshend instigated a flanking manoeuvre, made possible by air reconnaissance, which discovered a practical route through the marshes for elements of the 17th Infantry Brigade and cavalry to deploy against the left flank of the Turkish position. The action of this force, combined with an infantry bayonet charge, culminated in the rout of the Turkish defenders and the fall of Es-Sinn and Kut. The two 30 Squadron aircraft played a crucial role in these events, maintaining communications between Townshend and Brigadier W.S. Delamain, the commander of the flanking mobile column, before bombing the retreating enemy.

With the fall of Kut, the aircraft sought indications of the enemy strength located at Nasiriyah, on the Shatt el Hai (an ancient waterway linking the Tigris and Euphrates rivers), in the marshes to the north of Kut and along the Tigris river approaches to Baghdad. These operations were hampered by the difficulty of supplying replacement aircraft and supplies from Basra, and by the fragility of the Martinsyde. Difficulties aside, Reilly found that the Turkish defence of Baghdad centred on strong entrenchments at Ctesiphon, with an advanced guard twenty kilometres distant at Zeur. A second force of 2000 cavalry and camel-mounted troops at Kutaniyeh required constant surveillance to warn of any threat to the British position at Aziziyeh, only eight kilometres distant. In addition the enemy defences at Ctesiphon and Seleucia had to be carefully mapped, a task that was undertaken on a daily basis by White and Major E.J. Fulton. These flights, due to a combination of strong winds and the slow speed of the aircraft, took about two and a half hours, and engine failures (despite regular overhauling every 27 hours), were frequent.

White and Captain F.C.C. Yeates-Brown, Indian Army, undertook a photographic reconnaissance of Ctesiphon one early autumn morning. After flying at 1500 metres and evading Turkish anti-aircraft fire, the two airmen completed their mission, and turned for home and breakfast. Then the aircraft engine lost power. White opened the throttle and dived steeply for 60 metres in an attempt to remedy the problem. Initially, engine revolutions increased. White was forced to use a combination of prevailing wind, judicious use of available power and gliding to clear the general Ctesiphon area before landing adjacent to the Turkish redoubt at Zeur. The arrival of the aircraft confused the defenders long enough for White and Yeates-Brown to attempt to seek safety. Yeates-Brown, rifle in hand, stood in the observer’s seat to warn off possible pursuit and to indicate a safe passage through the broken terrain. Taxiing at speed over the cracked earth and aware of the possibility of pursuit, the airmen approached the vicinity of Kutaniyeh with some trepidation—White had dropped bombs on the troops during his previous return flights from Ctesiphon. By continuing in their sputtering aircraft along a roadway over a ridge some distance from the Tigris River, the airmen were able to bypass Kutaniyeh. Jolting overland for a further 25 kilometres, the obstruction to the fuel line or carburettor cleared, and the aircraft became airborne, miraculously enabling the crew to keep its breakfast appointment.

The seaplane flight also had its share of engine failures, one of which also involved White when he flew a Maurice Farman in the search for another flown by Gordon. Gordon’s absence was particularly distressing because with him was the Chief of the General Staff in Mesopotamia, Major General G.V. Kemball. The aircraft they were flying had suffered engine failure en route from Kut to Aziziyeh, and was discovered near the river by White, close to a large Arab camp. Circling the downed Farman, White came under attack by ground fire from the camp. It damaged an aileron rib and the propeller of White’s aircraft before he landed about a thousand metres from the downed seaplane. The Australian pilot ran to the riverbank with a spare rifle, located Kemball and returned to the aircraft to take flight for Aziziyeh. Gordon, who had left the site of the downed Farman, was saved by an Indian cavalry patrol that had noticed the descent of the floatplane.

White was not so fortunate on 13 November. He and Yeates-Brown volunteered to attempt to destroy telephone lines to the north and west of Baghdad before the British attack on Ctesiphon. The task involved the two airmen flying a round trip of 200 kilometres, meaning they had to carry cans of fuel on the aircraft. After bypassing the Turkish defences, White and Yeates-Brown discovered that their target ran parallel to a main thoroughfare used by bodies of soldiers in formation. The two airmen planned to land fourteen kilometres from the city where the telegraph line was within two hundred metres of the road. Locating the site, White circled to land. As he made his final approach he sighted a uniformed Turkish horseman calmly noting the landing of the aircraft, which could indicate the presence of enemy troops. Unfortunately the aircraft landed with the wind astern, forcing White to turn sharply to prevent damage to the front elevator. Despite judicious use of aileron and rudder, the pilot could not prevent the lower left mainplane colliding with a telegraph pole.

White traded shot after shot with the approaching Arabs, while Yeates-Brown successfully cut the wire by igniting several necklaces of gun cotton around two of the telegraph poles. The first explosion gave the Australians a brief respite from the advancing Arabs. Returning to the Maurice Farman under Arab crossfire, the airmen decided to attempt to taxi to safety. As they started the aircraft engine, a second charge exploded, snapping the telegraph wire and causing it to flail about. As they watched in horror, the wire swung around and coiled itself onto the aircraft. The only option for the airmen was to surrender. Both men were roughly handled and only the presence of a body of Turkish gendarmerie prevented them from being severely beaten. Both men became prisoners of war.

After the Turkish first and second defensive lines at Ctesiphon had been captured by Townshend’s force on 21 November, Turkish reinforcements forced the attackers to withdraw down the Tigris to Kut, where 13 000 British and Indian troops were surrounded. Two damaged BE-2C aircraft, half of the squadron reinforcements that had been sent from England, and a damaged Martinsyde remained at Kut. These had been operated and maintained by the British aircrew and the noncommisioned officers and mechanics, who joined their army colleagues in captivity. Nine Australians, of which only Flight Sergeant J.McK. Sloss and Air Mechanic K.L. Hudson subsequently survived captivity, also remained at Kut. Petre made flights from Al Gharabi over the beleaguered township to drop bags of grain (and a millstone to grind it) before he was posted to Egypt and, subsequently, to command a training squadron in England. The eight Australians at Basra were also sent to join the newly formed Australian Flying Corps in Egypt early in 1916.