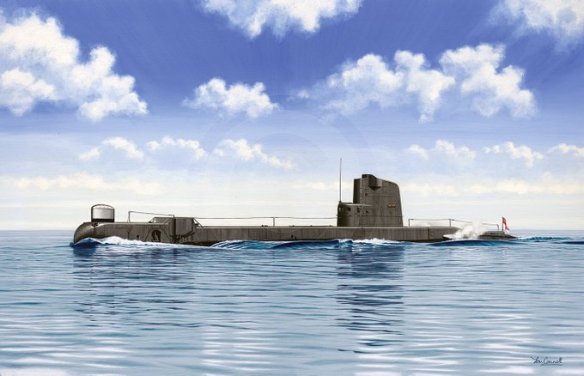

HMS Taciturn, one of the ‘Super T’ conversions, by Tom Connell.

Forays by British submarines into dangerous waters off northern Russia could only happen thanks to Hitler’s scientists and engineers.

In the closing weeks of the Second Word War a special commando unit, which boasted James Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming, as one of its operational planners, had raced for Nazi technological secrets. It wanted to secure them before they were destroyed or the Soviets got them. One of the key achievements of 30 Amphibious Assault Unit (30 AU) was capturing snorkel technology and also advanced submarines at Kiel on Germany’s Baltic coast. The British amassed nearly 100 surrendered German submarines at the Northern Irish port of Lishally, near Londonderry.

The Type XXI U-boat was a revolutionary kind of submarine, with high-speed batteries providing up to 17 knots submerged. This was extraordinary when the most Allied boats could manage submerged was 9 knots. Snorkel masts enabled Germany’s advanced diesel submarines to stay submerged – and safe from enemy attack – while venting generator fumes, recharging their batteries and sucking in fresh air.

Capable of impressive submerged endurance, via use of the snort mast (as the snorkel became known), the Type XXI had a sleek, supremely hydrodynamic hull form, with no external guns other than cannons mounted within the fin.

Combined with boosted battery power delivering high underwater speed a Type XXI did not have to surface to attack a convoy. It could fire 18 torpedoes (three salvoes) in around 20 minutes, which was as long as it took any other submarine to load a single torpedo.

The Type XXI could manage 50 hours submerged on batteries at full capacity (charged), an endurance that could be doubled by reducing energy consumption by 50 per cent. Other submarines could only achieve half an hour submerged on battery power, or 24 hours if they shut almost all equipment down. Using the snort to recharge the batteries, the prime objective for a Type XXI was an entire patrol submerged (and it took only three hours’ snorting to recharge batteries). It was also very stealthy at low speeds, using what were called creeping speed motors (on rubber mountings) to absorb noise. The Type XXI could safely dive up to 440ft (90ft deeper than the most modern Second World War-era British submarine), with a crush depth of more than 1,000ft.

Fortunately for the Allies only two ‘electroboots’ ever deployed on combat patrol during the Second World War. Crew training, technological defects common to any cutting-edge technology, and intensive bombing kept the majority of the 120 ‘electroboots’ non-operational. They were captured or destroyed. Even more remarkable were Type XVIIB boats, which used air-independent hydrogen peroxide propulsion, removing the necessity to even poke a snort mast above the surface.

Following a series of top-level meetings, it was decided the British, Americans and Russians should each have ten U-boats of all varieties, the remainder to be scuttled in Operation Deadlight.

The Soviets had limited contemporary experience on the open ocean in any kind of warship – during the Second World War the Red Navy fought mainly in littoral waters or operated along rivers and other inland waterways.

As a result the Russians requested that Royal Navy crews sail their allocated U-boats to Leningrad. The Soviets hid their lack of confidence on the high seas behind claims that they were being given defective submarines. The British had, though, delivered detailed seaworthiness assessments of the boats to their new owners.

The Americans, who took two XXIs, would base the design of their new Tang Class upon the Nazi boat type. They also reconstructed some of their newer Second World War-era submarines, under a programme entitled Greater Underwater Propulsive Power, or GUPPY, to incorporate German innovations.

Some Type XXIs were even pressed into service, the British operating two. While one was scrapped in 1949 after running on trials, the other was given to the French. They commissioned seven ex-German U-boats into their fleet, one of the Type XXIs seeing service into the late 1960s.

Even the Swedes, neutral during the conflict, recognised the necessity of acquiring revolutionary U-boats if their own navy was not to lose its status as a leading submarine operator. They raised U-3503 – scuttled inside their territorial waters – from the bottom of the Baltic and towed her to a naval base. Experts carried out a dry-dock inspection of her innovations before the submarine was scrapped. In the mid-1950s, when they needed to revive their submarine arm as part of NATO, the West Germans adopted a similar practice, locating U-boats sunk during the war and raising them.

A Project 611/Zulu IV showing the clean lines of this submarine. Production of this class as a torpedo-attack submarine was truncated, with the design providing the basis for the world’s first ballistic missile submarines.

Faced with a sudden need to match the West’s operational capability the Russians made the most of their inherited U-boats. Four of the ten they received from the British were Type XXIs, seeing service in the Soviet’s Navy’s Baltic Fleet for nine years. They also wasted no time in replicating the Type XXI in the Zulu and Whiskey classes of diesel boat. The British decided to implement what they had gleaned from the XXIs in a radical reconstruction programme for some of their T-Class submarines. Eight boats, including HMS Taciturn, were taken in hand between 1950 and 1956. Cut in two, they had a whole new section inserted containing two more electric motors and a fourth battery. It gave them a submerged top speed of between 15 and 18 knots but this could only be maintained for a short period. There were no external guns – these were removed as part of the rebuild – for they were given sleek streamlined outer casings. A large fin enclosed the bridge, periscopes and masts. Space was also made for specialist intelligence-gathering equipment.

Even as the Project 613/Whiskey design was being completed, in 1947-1948 TsKB-18 undertook the design of a larger submarine under chief designer S. A. Yegorov. 77 Project 611-known in the West as the Zulu-had a surface displacement of 1,830 tons and length of almost 297 feet (90.5 m). This was the largest submarine to be built in the USSR after the 18 K-class “cruisers” (Series XIV) that joined the fleet from 1940 to 1947. The Zulu was generally similar in size and weapon capabilities to U. S. fleet submarines, developed more than a decade earlier, except that the Soviet craft was superior in underwater performance- speed, depth, and maneuverability.

Taciturn and her reconstructed sisters were known as the ‘Super-Ts’. Externally she bore little, if any, resemblance to the submarine that had emerged from the Vickers yard at Barrow-in-Furness in the north-west of England in 1944. Taciturn was blooded in action against the Japanese. She sank a number of small vessels and also joined forces with her sister submarine Thorough, both using their 4-inch deck guns to bombard shore targets. The first to receive the Super-T conversion, Taciturn was a perfect solution for cash-strapped Britain, almost bankrupted by the Second World War, yet needing to match the rising threat of Russian naval power. Construction of brand-new boats was not possible for some years. Submarines built to combat Hitler’s Germany and militaristic Japan were refashioned using the fruit of Nazi science to become the best Britain could send against the Soviets.

It was Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Oliver who proposed the Royal Navy’s much reduced submarine force should take the war to the enemy.

Staking out Soviet submarine bases in the Kola Peninsula and on the shores of the White Sea, they would eliminate the threat before it could break out into the vastness of the Atlantic. Oliver, who first went to sea as a midshipman in the battleship Dreadnought in 1916, also saw action in the Second World War as a cruiser captain. He had even commanded carrier strike forces, so was a well-rounded tactician, though never a submariner. His April 1949 paper – written when Oliver was Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (ACNS) – gave impetus to the conversion of Taciturn and her seven sister boats into Super-Ts. If things turned hot they would sink Soviet boats in the Barents Sea, hunting down and killing them with torpedoes, or laying mines.

The precedent for using submarines to destroy other submarines had been set in the recent world war. British boats sank 36 enemy submarines, while the Americans claimed 23 Japanese. All but one of the targets was sunk while on the surface. The distinction of hunting and killing an enemy submarine while both were submerged fell to Lieutenant James Launders in HMS Venturer. His successful attack on U-864 off Norway, on 9 February 1945, remains the only one of its kind and was achieved after Venturer trailed the zig-zagging enemy boat for some hours. Having fixed the German’s position – and likely future track – via ASDIC, Launders fired a spread of four torpedoes, at 17-second intervals. U-864 managed to evade three, but steered into the path of the fourth and was blown apart.

By the mid-1950s Britain’s navy simply had to be more aggressive and push its submarines forward, to repeat Launders’s remarkable feat in order to make up for withered global sea control capability. It had not only ceded supremacy on the high seas to America, but was facing relegation into third place by the burgeoning maritime might of the Soviets. Even before the Second World War Stalin had been urging Red Navy chiefs to build a battle fleet that would break free of the traditional coast-hugging role. Within three months of the fighting in Europe ending, Stalin decreed the USSR should create a powerful ocean-going navy. Unfortunately, the vessels that started to come off the slipways, such as Sverdlov Class cruisers, were outmoded before they were launched. They replicated Nazi technology without taking it much further.

May 1955 saw the creation of the Warsaw Pact, which militarily melded the USSR with its satellite states in Eastern Europe to counter NATO.

Emboldened by Kremlin concessions to protests for more freedom in Poland, on 23 October 1956 200,000 Hungarians took to the streets, objecting to the presence of Russian troops in their country. Their revolution was brutally suppressed by the Red Army. Around 20,000 Hungarians paid with their lives for daring to try and cast off the Soviet yoke.

Even as Russian tanks crushed dreams of democracy on the streets of Budapest, the Soviets were threatening nuclear war against Britain and France in response to an invasion of Egypt.

The Americans did not back their Second World War allies’ bid to take back control of the Suez Canal by force, while the new Soviet overlord, Nikita Khrushchev – supporting the fervent Arab nationalist leader Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser – warned he would unleash ‘rocket weapons’ against London and Paris.

Despite a measure of military success, it was President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s fury at his allies going it alone that forced them, ultimately, to withdraw from Suez. The Cold War had turned nasty, but open warfare between the two armed camps had been avoided. Beyond confrontations on land, lethal shadow boxing between the naval forces of East and West was already a facet of the Cold War confrontation.

In April 1956 the mysterious disappearance, and probable murder, of a frogman trying to spy on Soviet warships within sight of Taciturn’s home base in Gosport heightened tension.

The Russians were returning the courtesy of a British naval diplomatic mission to Leningrad the previous year. As the aircraft carrier HMS Triumph and her escorts sailed up the river Neva, they passed building yards containing dozens of surface warships and submarines in various states of completion. Many in the British naval community had refused until then to believe the Soviets really were undertaking such an ambitious programme. Their hosts had not actually meant to leave so much on display. When the British naval squadron sailed back down the Neva, smokescreens were generated in front of the building yards. With Triumph’s height as an aircraft carrier, it was still possible for naval intelligence specialists to take photographs.

When the Russian Navy sent the cruiser Ordzhonikidze to Portsmouth she carried no less a person than Nikita Khrushchev. On the British side there was a great desire to learn as much as possible about the Russian warship – a temptation too hard to resist, especially as she was parked in the centre of the Hampshire harbour.

Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb

Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb, a well-known veteran of daring underwater exploits in the Second World War, was ordered by M16 to see what he could find out about the Ordzhonikidze. Crabb had already covertly inspected the propulsion of a Sverdlov Class cruiser in 1953 -Sverdlov herself, when the vessel was anchored at Spithead for the Coronation Review of Queen Elizabeth II – discovering an innovative bow thruster. Three years later it was worth seeing what else might be below the water-line. Crabb stayed at the Sally Port Hotel in Portsmouth with his MI6 handler, who signed the register as ‘Mr Smith’. After the former naval officer departed to carry out his dive, ‘Mr Smith’ cleansed the room of Crabb’s civilian clothes and other belongings. Newspapers were soon carrying stories about Crabb disappearing on an espionage mission. The Navy maintained he was testing new diving equipment in Stokes Bay, just down the coast, rather than diving in Portsmouth Harbour. Soviet sources said sailors aboard the cruiser had spotted a frogman. An official complaint was lodged with the Foreign Office. Nobody publicly admitted to anything. The head of MI6 was forced to resign by the Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, for launching an ill-advised mission without specific authorisation by the government. The Navy had allegedly assisted MI6, providing a boat and a naval officer to support Crabb’s dive.

It was claimed the local Special Branch squad sent someone to rip out relevant pages in the hotel register.

The furious British government cancelled various military intelligence-gathering operations, including deploying submarines into the Barents Sea. This caused massive loss of face for the Royal Navy but in the absence of British boats taking part, the Americans received a confidential briefing on surveillance skills from Cdr John Coote. He had captained the Super-T boat HMS Totem on at least one recent spying mission in the Arctic. At one stage Totem had to surface so one of her officers, Peter Lucy, could carry out temporary repairs to a defective S-band search-receiver. Mounted in the periscope it picked up potential threats by detecting radars of searching aircraft and surface vessels. Normally such a procedure required a workshop, but Totem was hundreds of miles from home. Lucy would be working solo in the housing at the top of the fin and if the Russians loomed over the horizon Coote would dive the boat under him. Lucy would have to swim for his life and, if captured, probably suffer a grisly fate at the hands of Soviet interrogators. Several months later, Cdr Coote told senior British naval officers and the US Navy that intelligence gathered on the Soviet Navy in the Barents had revealed a weakness in its AS W capabilities. To gain such an edge risks were justified.

Not long after Coote showed the Americans how valuable Royal Navy missions in the Barents were, the British PM was warned that without them the US-UK defence relationship was at risk. It was felt the Americans would press ahead with the submarine surveillance programme anyway, denying the British access to data collected. Eden was still worried about the possibility of such forays sparking a hot war, so he remained true to one of his favourite sayings: ‘Peace comes first, always.’

Eden’s subsequent Suez misadventure led only to national humiliation and his resignation, in January 1957. Harold Macmillan, a firm supporter of the Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’, succeeded him. The new PM authorised resumption of British participation in submarine deployments to the Barents. He was only too well aware that Soviet military doctrine was following a new direction that would require intelligence gathering in Northern seas. For while Khrushchev agreed with the need for a powerful global navy he saw there was no point in trying to match Western strength, but rather to outflank it. A battle-cruiser programme was cut, the number of Sverdlovs under construction revised downwards. Khrushchev announced a ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’, which sought to steer the Russian armed forces away from huge, lumbering conventional formations, to smaller high-tech units. They would deploy missiles with nuclear warheads.

Many of these new weapons would, from the 1950s onwards, be tested at firing ranges and detonation test sites located on the island of Novaya Zemlya. The Barents, Arctic and Kara seas washed its shores, but it was from the western side that it was most approachable by submarines.

To Khrushchev nuclear weapons were a means to achieving superpower punch while enabling a reduction in military spending, diverting resources instead to the civilian economy. Submarines armed with missiles would be a key component of the USSR’s defence revolution. To enact this element Khrushchev turned to a man he had served alongside during the 1941–45 war, Sergei Gorshkov, making his old comrade in arms Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy in 1957. The ascent of Gorshkov would reinvigorate the Soviet Union’s naval forces and make them more aggressive, both in home waters and overseas.

On 9 June 1957, what remained of a corpse in a diving suit – minus head and hands – was found in the sea off Chichester. It was difficult to identify, although a scar on a knee was supposedly a match for Crabb. While an inquest recorded an open verdict the coroner decided that, on balance of probability, it was him. One popular theory was that Crabb had been spotted by the Russian cruiser’s own frogmen on security duty. He had either been captured alive and taken aboard ship or killed in the water. More recently it has been suggested Crabb was sucked into the Ordzhonikidze’s screws. When at anchor in a foreign port, the cruiser turned them vigorously from time to time as a standard counter-measure against snooping frogmen.

With Crabb apparently suffering a grisly fate at the hands of the Soviet Navy – during a spying mission just a few hundred yards from Taciturn’s home berth at HMS Dolphin – did any submariner need to be reminded the Cold War could be fatal?