A Lancastrian army of some 6-14,000 men under James Touchet, Lord Audley, intercepted a Yorkist force of just 3-5,000 men (more probably the higher of these figures) under Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, marching to join the Duke of York at Ludlow. It would seem that Salisbury drew up with his left and part of his front secured on a stream with steep banks and marshy ground at the edge of a wood, and his right, which was otherwise exposed, protected by a laager made up of his baggage wagons. Three Lancastrian charges, one with cavalry and two on foot, were repulsed with considerable losses after being disordered crossing the ditch to Salisbury’s front, Audley being killed. After most of the afternoon had been spent fighting the Lancastrians broke in rout at 5 p. m. and were closely pursued by the victorious Yorkist. 2,000-2,400 Lancastrians died in the battle and a further 500 defected to Salisbury, while the Yorkists lost only 200 men.

23 September 1459

Later in 1458 Warwick deigned to answer a royal summons to explain his assault on the Hanse ships. In London the Earl’s party became involved in a fracas with royal retainers. This swiftly degenerated into a brawl and the Neville party claimed they were obliged to fight for their lives, to break free and escape by water. From now on Warwick held his post in Calais in defiance of the King. Battle lines were drawn once again.

Moderation was the first casualty; the middle ground was completely eroded. Buckingham, no admirer of Warwick, with whom he was personally at odds, refused to shift his core loyalty away from the throne. When Margaret summoned a council to Coventry in June, prominent Yorkists were pointedly excluded, including George Neville and Bourchier. Richard, Duke of York, was fully aware of this manoeuvring and prepared to resist what he perceived as the inevitable application of force to reduce his affinity. He planned to gather his strength in the Yorkist heartland at Ludlow; Warwick would bring over a strong detachment from the Calais garrison, whilst Salisbury would muster his northern retainers.

Even at this stage York did not necessarily intend to fight. He and those of his fellowship were painfully aware, however, that only a strong show of force would deter the Lancastrians who now viewed themselves as being in the ascendancy. The court faction could still emerge victorious from a confrontation if it could prevent the Yorkists from achieving their full muster, defeating their presently scattered detachments in detail. Warwick’s Calais contingent had to run the full gauntlet of England but did so with elan, neatly sidestepping Somerset’s attempt to block them. The main Lancastrian force, mustering in the Midlands, was commanded by Buckingham, whilst Queen Margaret had moved to Eccleshall to join the strong detachent under James, Lord Audley, fast approaching Market Drayton. This was a very substantial force. Jean de Waurin, our most complete chronicler, puts Audley’s numbers at 10,000, the majority mounted.

Salisbury was marching for Ludlow; with him his sons Sir John and Sir Thomas, together with Sir John Conyers, Sir Thomas Harrington and Sir John Parr. His numbers were considerably inferior to the Lancastrian contingents that were poised to intercept him, though, as skilful on the march as his son, he avoided Buckingham. If Margaret was to frustrate a full Yorkist muster she would have to deploy Audley’s army to stop Salisbury. By the chill dawn light on 23 September, the two forces were already jockeying for position, prickers on both sides covering the ground. The Yorkists were advancing along the line of the road that runs from Newcastle-under-Lyme to Market Drayton, their movement screened by Burnt Wood straddling the highway. The Lancastrians marching to meet them. As the Yorkists passed through the belt of trees, scouts brought intelligence that the Queen’s forces were near, marshalling in battle array behind a substantial `forest hedge’.

With the woodland to their rear, also protected by a hastily dug trench, Salisbury’s officers completed their deployment. As their right flank was `in the air’, the Earl commanded a wagon leaguer be positioned so as to create both an anchor and obstacle. Knowing the odds were unfavourable, Salisbury intended to stand on the defensive and threw out a line of stakes along his front. A stream, the Wemberton Brook, ran along the left flank then bore diagonally through a valley running between two shallow ridges; it was along the line of the easterly eminence that the Yorkists had taken position. During the remainder of the morning there was something of a stand-off. It would be obvious to Audley that, though his force was the greater, the Yorkists were strongly posted. Besides, Salisbury and his officers were seasoned soldiers and their men, in many instances, veterans. The situation changed in the early afternoon when the Lancastrians appear to have come to the erroneous conclusion that the Yorkists were seeking to disengage.

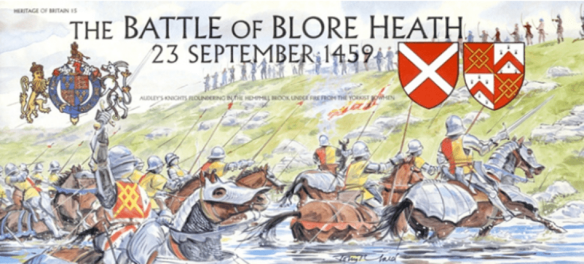

This, as Colonel Burne, writing in More Battlefields in Britain in the 1950s argues, was purely a ruse, intended to prompt Audley into attacking. Whether it was only the centre of the Yorkist line that was involved in this Parthian retreat, or whether the flanks also showed signs of withdrawal, is unclear. The impression was convincing enough to persuade Audley it was time to advance his cavalry – there are certainly similarities between Blore Heath and some of the battles of the Hundred Years War. The Lancastrians trotted down the slope and negotiated the stream, by no means a major obstacle, but a distinct hindrance to so great a press of mounted men. With no attempt at manoeuvre, Audley cantered toward the Yorkist line. Salisbury and his men, having received the unction and commended their souls to God, strung their bows and began to shoot. Audley may have been supported by a contingent or contingents of his own archers but the cavalry fared badly, perhaps as many as 500 falling to the arrow storm.

Disconcerted, Audley’s survivors from the first wave fell back, leaving a field piled with fallen riders and horses. He re-formed and came on again, with similar consequences, except that Audley himself also fell dead (the spot where he died now the site of the battle stone). With their commanding general lost, the Lancastrians experienced both a change of commander and a shift in tactics: John, Lord Dudley dismounted his horsemen and formed a foot column which he led to renew the attack, skirting or stumbling over the mounds of dead or moaning men and mounts. This field, uncannily similar to Poitiers, now became a slogging match, an infantry melee of hacking bills, the noise of battle rolling like thunder over the ground. The fight dragged on for several bloody and exhausting hours, neither side gaining significant advantage, men swaying in the ritual dance of slaughter, the lines shifting and heaving. The Lancastrians’ final reserve was a mounted rearguard that could be thrown in to exploit any gaps that the foot might open in the Yorkist line – the day could yet be won.

For whatever reason, perhaps a failure of morale, the rearguard chose to quit the field as lost, their defection spreading like a contagion to the infantry who now gave way. A body of the defeated avoided the horrors of pursuit by a timely shift of allegiance; the rest were harried mercilessly. The Yorkists were particularly energetic in the chase, the hunt becoming confused and disorganised. Squads of the victors looted the dead, pelted after fresh victims, and generally engaged in indiscriminate pillaging. A number of the vanquished were brought to ground some two miles west of the main fight, at a place known as `Deadman’s Den’, by the little River Tern. Aside from Lord Audley himself, a rash of knights were slain – Sir Hugh Venables of Kinerton, Sir Thomas Dutton of Dutton, Sir Richard Molineux of Sefton, Sir John Dunne and Sir John Haigh, with perhaps as many as two thousand of the commons. The Yorkists escaped without the loss of any gentry and with only a handful of dead amongst the rank and file.

This intemperate pursuit proved unfortunate for Sir Thomas Harrington and the two Neville knights, who ran into a rearguard the next morning by Tarporley Bridge and were all captured, destined to spend the next nine months incarcerated in Chester Castle. First blood in the campaign thus went to York. All of his contingents, though widely disparate, succeeded in gaining their objective, destroying a Lancastrian army en route. For the Queen, this was both a tactical reverse and a strategic setback. She had previously summoned the Stanleys, Lord Thomas and his brother Sir William. The former was Salisbury’s son-in-law and, despite protestations of loyalty, he avoided the muster. Sir William, less vacillating, threw his lot in with the Yorkists. With their available forces concentrated at Ludlow the Yorkists had successfully frustrated attempts to prevent a full muster. York was at the heart of his dominion, with his affinity in numbers and under arms, a notable victory under their collective belt. He could, perhaps, look forward to the outcome of any further stand-off with some degree of equilibrium. Yet if this was the case, he would have cause to regret his complacency.

York’s manifesto was in the form of an apologia to Henry, excusing his and his fellowship’s outwardly treasonable actions. The Yorkists were on very uncertain ground; however real the perceived threat, they had taken up arms in defiance of their sovereign and had made war on his appointed officers. Margaret riposted by offering a general amnesty, only excluding those who had had a hand in Lord Audley’s destruction. As a war of words bickered, the Lancastrians assumed the tactical initiative, advancing northward towards Ludlow.