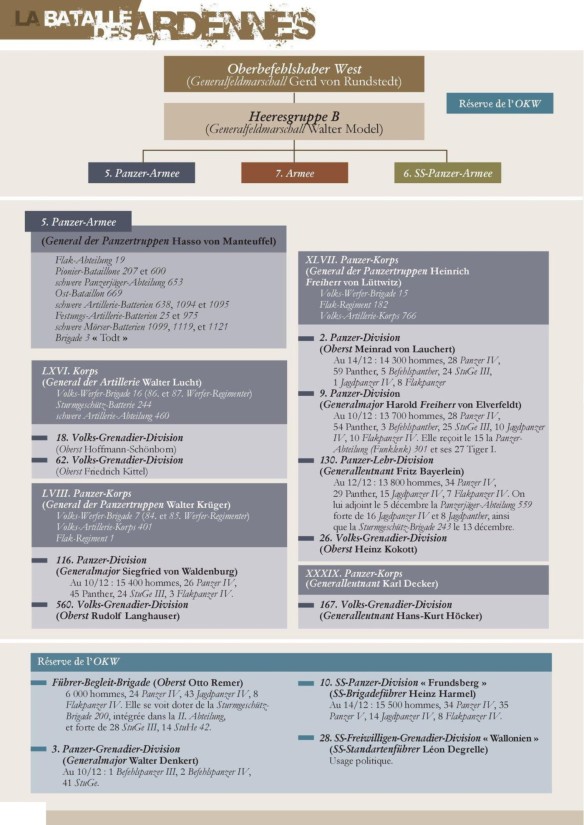

Today Bastogne is less than an hour’s drive from Dasburg, which straddles the Our. In 1944, those same twenty-five miles were narrow, twisting, largely unpaved and particularly muddy; the road network only improved west of Bastogne. Lüttwitz’s mission boiled down to one essential: Bastogne had to be taken if the Meuse was to be reached. Should his panzers fail to take the town, the Volksgrenadiers were to besiege it, leaving the tanks free to continue their dash to the Meuse, which they were ordered to reach by the end of the second day. With his corps advancing on two axes, Lüttwitz envisaged Panzer Lehr as being able to reinforce or relieve 2nd Panzer, or the 26th Volksgrenadiers, and to exploit any opportunity that arose.

An important German figure in the story of the Bulge was General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, a baron, like his army commander. This old school aristocrat was yet another example of an individual who epitomised all that Hitler loathed nevertheless doing well in the classless Third Reich. With his monocled right eye, peaked cap and huge Iron Cross swinging from the neck, Lüttwitz looked like the stereotypical German officer from central casting. Looks can be deceptive: he was clever and an instinctive leader. He had been appointed Ensign of a smart Uhlan cavalry squadron in October 1914, served in mounted regiments on the Eastern Front from 1915 to 1917, fronted a reconnaissance battalion in Poland in 1939 where he was wounded, missed the French campaign but recovered in time for Operation Barbarossa in 1941.

Two years later Lüttwitz had risen to command a panzer division, and on 5 September 1944, the bearer of a Knight’s Cross and Oak Leaves, he was promoted to lead the XLVII Panzer Corps. On 27 October, as we have seen, he had already caught the British napping in his two-division attack further north, at Meijel in the Peel Marshes, and the lessons of stealth, surprise, speed and momentum in difficult country cannot have been lost on him. Although Lüttwitz turned forty-eight just ten days before he led his formation into the Ardennes, there is evidence that he was physically exhausted, having commanded formations in action almost without a break for nearly three and a half years. Photographs of him at this time show a man looking far older: evidence of the strain of continuous fighting, surely shared by many of Hitler’s combat leaders.

Oberst Heinz Kokott’s 26th Volksgrenadier Division was a ‘hollowed out’ formation, retaining a few veterans from the Russian and Normandy fronts, but mostly Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine replacements. Like all Volksgrenadier units, their mobility was hampered by total reliance on horses, some of which were a tough Russian breed, used to winter. Nevertheless, they were up to strength with an outstanding cadre of sub-unit leaders and experienced troops, on whom the new arrivals could lean for experience. Its Panzerjäger (anti-tank) battalion had its full complement of fourteen tracked Hetzer tank destroyers, and an impressive forty-two 75mm anti-tank guns, making the 26th one of the best-equipped Volksgrenadier units in the Ardennes.

Though protected by the opening bombardment and in the dark, before they even reached the river Kokott’s Volksgrenadiers had to penetrate hundreds of felled trees, copious barbed wire entanglements and large areas of mines, all left behind by retreating German troops earlier in the year. Next, they had to navigate the fast-flowing Our by rubber assault craft, climb the not inconsiderable far slopes, and overwhelm the forward American lines. Meanwhile, bridging units were to prepare crossing sites for the waiting 2nd Panzer Division. Superbly able and energetic, the bespectacled, buck-toothed Kokott had joined the German army on 1 October 1918 just before the Armistice and had carried on as a career officer, mostly serving in Russia, where he won a Knight’s Cross in 1943. An unlikely brother-in-law of SS chief Heinrich Himmler, in late 1945 the distinguished American historian Colonel S.L.A. Marshall found him ‘a shy, scholarly and dignified commander who never raises his voice and appears to be temperate in his actions and judgments’.

The 2nd Panzer Division was Lüttwitz’s old division, which he had led in Normandy. Raised in Austria by its first commander, Heinz Guderian, in 1935, and known as the Wiener (Vienna) Division, it had fought in Poland, France and the Balkans. In Russia its forward units had witnessed the winter sun glinting off the onion domes of the Kremlin on 2 December 1941: the high tide of the Wehrmacht’s advance into Russia. Later it was transferred to the west before D-Day in 1944. On the eve of the Normandy invasion, the formation was several hundred men over-strength and reported ninety-four operational Panzer IVs and seventy-three Panthers: a very strong unit.

Fighting at Mortain alongside the 116th Greyhounds, both divisions lost heavily in the Jabo Rennstrecke (fighter-bomber racecourse) that was Normandy. By 21 August, they had escaped from the Falaise Pocket with little more than an infantry battalion left; it possessed not a single surviving tank. Although refitted and re-equipped, its War Diary indicates that on 10 December it could boast only 49 Panthers, 26 Panzer IVs and 45 StuG assault guns.

It was still powerful, at 120 tanks and assault guns, but far less so than its peak Normandy strength of 167, and half the size of the US Third Armored Division. Nevertheless, some Panthers were the latest factory-fresh model, equipped with novel infra-red optics for night-fighting. Noteworthy was the high number of turretless assault guns, rather than true tanks, that 2nd Panzer deployed and more evidence of the dilution of its strength. By 1944 German armoured doctrine was to break down into self-contained Kampfgruppen (battlegroups) for combat, which comprised tanks, engineers, artillery and mechanised infantry in half-tracks, each named after its senior commander.

Until 14 December, Generalmajor Henning Schönfeld had led 2nd Panzer Division, since taking over from Lüttwitz on the latter’s elevation to corps command. However, the fifty-year-old Schönfeld, like many of his contemporaries, felt the resources allocated to him were woefully inadequate to the task and voiced his opinion too vociferously to his superiors, Lüttwitz and Manteuffel. It cost him his division. In the post-20 July atmosphere, where a lack of enthusiasm could be misconstrued in some quarters as treason, Manteuffel felt he had no option but to remove him immediately. A promising young colonel, who had attended a divisional commander’s course and recently relinquished leadership of a panzer regiment in Russia, was found and the thirty-nine-year-old Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert found himself the new commander of 2nd Panzer, appointed on the day before the offensive was launched.

The official reason for the departure of Schönfeld, an infantryman by background, was stated to be his lack of experience with armour, but that was clearly nonsense. It underlined the extreme anxiety that was attached to executing Hitler’s pet project as well as possible. These were the days anyone could face a firing squad if the Führer or Himmler perceived in them a lack of vigour. Being appointed the day before to lead a division at the spearhead of a major offensive must have been nerve-wracking for Lauchert, but on the other hand that is the nub of the military profession – coping with the unexpected quickly – and he managed well although, as he later complained, he hadn’t even time to meet his regimental commanders.

Lüttwitz’s other tank unit was the 130th Panzer Division, better known by its designation Panzer Lehr (the ‘Panzer Instruction’ unit). Its task was to reinforce the advance wherever Lüttwitz saw an opportunity. It had been formed in France that January by combining the staff and instructors of the Wehrmacht’s panzer training schools and demonstration units into a combat formation, which made it something of an elite, highly experienced unit from birth. The Lehr had served in Normandy where, like so many armoured formations, it had been almost annihilated, fielding just eleven tanks, no artillery and fewer than 500 men by 1 September. Its commander later described the experience of being under Allied air attack, which underlined how battle-hardened the division was by December 1944. Other veterans fighting in the Ardennes would echo this, where the same punishment was repeated:

The duration of the bombing created depression and a feeling of helplessness, weakness, and inferiority. Therefore the morale of a great number of men grew so bad that they, feeling the uselessness of fighting, surrendered, deserted to the enemy, or escaped to the rear, [in] as far as they survived the bombing. The shock effect was nearly as strong as the physical effect. For me, who, during this war, was in every theatre committed at the point of the main effort, this was the worst I ever saw. The well-dug-in infantry were smashed by heavy bombs in their foxholes and dugouts or killed and buried by blast. The whole bombed area was transformed into fields covered with craters, in which no human being was alive. Tanks and guns were destroyed and overturned and could not be recovered, because all roads and passages were blocked.

This was the story of Allied air supremacy for the rest of the war – unless the fog of an Ardennes winter could intervene.

Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein, as we’ve seen, was the popular, high-profile commander of Panzer Lehr, both in Normandy and the Ardennes. One of Germany’s younger divisional generals at forty-five, he just caught the end of the First World War, being drafted in 1917. After the war he went through officer training in 1921 and was lucky to be one of the 4,000 officers retained in the reduced Reichswehr. The invasion of Poland saw Oberst Bayerlein as chief of staff in Guderian’s panzer corps, and he continued as Guderian’s right-hand man for the invasion of France the following year, crossing the Meuse at Sedan on 14 May. He had drafted Guderian’s corps operations order to undertake that opposed river crossing with three divisions (over 20,000 men) – it came to a succinct two pages. Bayerlein gained a high profile and he was next posted as chief of staff to Rommel’s Afrika Korps during 1941–3.

His appointment to Panzer Lehr in 1944 was Guderian’s doing; the war required that the Wehrmacht’s elite armour training and demonstration units be broken up and drafted into a division. Guderian (as Inspector-General of Armoured Troops) wanted to protect this investment of his finest personnel with a brilliant commander. He chose Bayerlein, who had served in every theatre (east, west and Africa), experienced Allied tactical air power at first hand, and worked as chief of staff to the key exponents of armoured warfare, Guderian and Rommel. Before Herbstnebel Bayerlein was concerned at operating with Kokott’s 26th Volksgrenadiers who were to precede his advance, due to the differential mobility of Panzer Lehr with the almost medieval Volksgrenadiers, equipped with horses and bicycles; his anxiety would prove justified. However, as Manteuffel and Lüttwitz soon came to realise, Bayerlein was also exhausted and past his best by December 1944.

Although re-equipped when earmarked in September for the Ardennes, Panzer Lehr was deployed to counter Patton’s thrust into the Saar region, and had to be refitted again in early December. Then its tank commander, Oberst Rudolph Gerhardt, reported 23 Panthers, 30 Mark IVs and 14 assault guns operational – a far cry from the 14,699 personnel, 612 half-tracks and 149 panzers of its peak strength in June 1944.27 In terms of armoured infantry, both Panzergrenadier regiments were between 40 and 50 per cent under their authorised strength, though more replacements were ‘promised’. As the assault guns came from an attached brigade, this meant that Panzer Lehr was actually at, or below, half-strength and should not have been deployed at all, even though Manteuffel felt all of his three panzer divisions ‘very suitable for attack’ in mid-December, even if lamentably short of equipment.

From this roll-call of German commanders it becomes clear that a majority of Hitler’s panzer commanders seemed to be Freiherren (barons), Ritteren (knights) or have acquired the suffix ‘von’ after their name, meaning they or an ancestor owned the terrain after which they took their surname. Hitler may have been suspicious of his aristocrats, but there were a surprising number in the Wehrmacht, and particularly in the Panzerwaffe (tank arm). As in most European nations, medieval landowners had ridden into battle, which evolved into their descendants joining cavalry regiments. With the decline of the horse for offensive and shock action (as opposed to logistics), cavalry officers adapted by crewing armoured cars and tanks, hence most German mounted units became part of a panzer division. As many of these officers had been brought up together, were educated as the same schools or interconnected by marriage, such informal familiarity often helped command and control in battle.

All these divisions constituted the ‘shock wave’ of Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army. However, if necessary, the baron could – and, indeed, did – request reserve formations from Army Group ‘B’ or OKW. Several were committed to combat in the later stages of Herbstnebel, though permission to do so had to be granted at the highest level. They included the Führer-Begleit (leader’s escort)-Brigade, an expansion of Hitler’s personal bodyguard battalion – not an SS formation, but one filled by the army. In 1939–40 this had been commanded by an obscure colonel named Rommel, but it had gradually been enlarged to become an elite formation which fought on the Eastern Front. When refitting after battling the Soviet steamroller in East Prussia, Hitler had ordered it to head west in early December 1944 to prepare for the Ardennes. We have already seen how Ultra had detected its presence and considered it a combat indicator of ‘trouble brewing’. This was because it was really a mini-division rather than a brigade, and comprised just over 6,000 battle-hardened personnel, including 200 officers. A very powerful formation, it included a armoured regiment of two battalions (nearly 100 tanks) and Panzergrenadier regiment of three battalions, with around 150 half-tracks, a Flak regiment and an artillery battalion.

Fully motorised, it reflected Hitler’s bizarre favouritism – showering equipment on some units at the expense of others: the formation had more vehicles than all the Volksgrenadier divisions combined. Its presence in the Ardennes was undoubtedly political: Hitler expected another of his favourites – like the Sixth Panzer Army – to shine with National Socialist fervour in the forthcoming battle. In background, experience and equipment it was on a par with Waffen-SS formations, and its presence was also a reward for its commander. Oberst Otto-Ernst Remer was another of Hitler’s protégés, who had played a key role in foiling the 20 July 1944 Stauffenberg plot in Berlin. As a result, on 21 July Major Remer had been promoted straight to Oberst. With the Knight’s Cross and Oak Leaves glinting at his throat, the tall, athletic Remer, thirty-two, was resourceful, highly dangerous and had already proven himself rabidly National Socialist.

It would not be until 4.00 p.m. on 18 December that he was ordered to join the battle and take his Führer-Begleit-Brigade to the St Vith front under Lüttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps; Manteuffel, though glad of its combat power, also felt Remer to be Hitler’s personal spy in his camp.30 Also in OKW reserve was the Führer-Grenadier-Brigade, which sprang from similar origins, and likewise was considered an elite and equally unusual formation, very similar in size and capability to its twin, the Begleit-Brigade. Not released from OKW until 22 December, this powerful unit was scattered along march routes in traffic jams, when it was ordered south to face the US Third Army.

As we consider Manteuffel’s Fifth Army, several themes emerge. All his four infantry divisions, the Volksgrenadiers, were new formations which had undertaken little training, and none as divisions. If their leaders were experienced, the vast majority of grenadiers were new to combat. One Volksgrenadier commander, Bader, was in hospital and the battle run initially by one of his sub-unit colonels, Langhäuser. If the panzer divisions were formed of veterans, they were hopelessly under- strength, and two of the three divisional commanders, Waldenburg and Lauchert, were new. The third, Bayerlein, was tired. We have seen how General Baptist Kneiss, a corps commander in Brandenberger’s Seventh Army, took a month’s leave and returned the day the offensive began, which hardly seems professional. Perhaps Kneiss was making the same point as the sacked Generalmajor Schönfeld of 2nd Panzer – but in a subtler way – that he, like Field Marshal von Rundstedt, had little faith in the offensive and thus wanted no part in planning it.

All of this put the attacking force at an enormous disadvantage, with little pre-battle training and none at higher formation level. Few of the commanders had worked together, so could not guess their superiors’ or subordinates’ intentions; combat flows more smoothly when commanders instinctively sense their colleagues’ movements, the result of months or years of fighting together.

This was in great contrast to Middleton’s VIII Corps. Although many were tired and degraded because of the Hürtgen battles, the Americans had been campaigning together since June in Normandy, and even the newcomers, such as Jones’s 106th or Leonard’s 9th, had trained together for longer than any of the Volksgrenadier units. The US Army – whether experienced but tired, or green and nervous – were vastly better resourced than their Wehrmacht counterparts. Manteuffel’s army alone boasted over 15,000 horses, whereas the Americans relied entirely on wheeled and tracked mobility, with unlimited fuel, now that Allied logistics flowed from Antwerp and the Red Ball Express had build up a reserve of combat supplies close to the front.

All the panzer divisions were woefully understrength; many of the anti-tank battalions were deficient in tracked tank destroyers, air defence units reported shortages of Flak guns, and ammunition and gasoline were in critically short supply. As Rundstedt admitted to the historian Liddell Hart in 1945, ‘there were no adequate reinforcements, no [re]supplies of ammunition, and although the number of armoured divisions was high, their strength in tanks was low – it was largely paper strength’.

The morale of German troops picked up when they saw the extent of resources carefully husbanded and camouflaged all around them. Perhaps they could win, after all? Gefreiter Hans Hejny, with 2nd Panzer Division, mirrored the experience of any soldier who has had to drive with minimal lighting in a convoy at night. It is exhausting on the eyes (the consequence is usually the ‘bug-eyed’ look tired soldiers exhibit in daylight), for a moment’s lapse of concentration can lead to a wrong turning or worse. Hejny remembered a trek to the concentration area, at the head of his armoured engineer battalion: ‘Orders were given quietly, and lights were dimmed. Only a thin ray of brightness came from the convoy-light made the lane even barely visible. It was hard to see the roads and we had to concentrate to avoid falling into the trackside ditches. We reached the top of a hill and could see the vague outlines of Luxembourg. The road extended from a forest into a plain and ahead were the tail-lights of another column gliding downwards and disappearing into the woods.’