The forty-three-year-old Gruppenführer Hermann Priess commanded the I SS Corps, formerly Sepp Dietrich’s old formation, which contained 1st and 12th Panzer Divisions, totalling around 240 panzers on 16 December. We have seen via Dietrich’s career how the Leibstandarte expanded from a motorised regiment in 1939 to the largest division in the armed forces by December 1944. Priess himself had joined the nascent SS in 1934 and fought in Poland, France, Russia, where he led the 3rd SS-Panzer Division Totenkopf (Death’s Head), and in Normandy leading a corps. Agile and clever, he took over his formation on 30 October. Even though an SS panzer corps sounded the very epitome of a ruthless, fully motorised formation that would slice its way through any opponent or terrain in Herbstnebel, Priess was allocated three infantry divisions in addition; their job would be to carve their way through American positions to allow the following panzer divisions unimpeded passage.

The infantry included the 277th Volksgrenadiers of Oberst Wilhelm Viebig, an artilleryman by background, who had served in Russia on Field Marshal von Manstein’s staff, and assumed command of his division on 4 September. Though formed from the pitiful remnants of a formation that had crawled out of Normandy, few of Viebig’s headquarters staff, officers or NCOs were battle-hardened. Many of the replacement grenadiers were Volksdeutsche, hailing from Croatia, Alsace (whose loyalty was tested, holding French sympathies), and Vienna, then under threat from the Soviets. Their crest (a ‘V’ crossed with a sword, referring to Viebig) was painted on their few vehicles, but most mobility rested on bicycles and horses. Field Marshal Model, who inspected them on 28 November around Dahlem, was well aware of their deficiencies but insisted they would perform well through ‘ardour and spirit’. At only 80 per cent strength, and with one of their eight battalions already committed to defending a portion of the Siegfried Line elsewhere, the 277th’s mission was to break through to the Elsenborn Ridge, north of the Losheim gap.

Alongside Viebig was the 12th Volksgrenadier Division, under Generalmajor Gerhardt Engel, an impossibly distinguished combat commander and already holder of a Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, an adjutant on Hitler’s staff from 1938 to 1940, and possessing high decorations from Italy, Serbia, Romania and Finland. A high-flying officer, he had taken over his Volksgrenadiers on 9 November and received advancement to Generalmajor on 15 November, only three months after his promotion to Oberst. One of the best Volksgrenadier units allocated to Herbstnebel, their badge of a shorting bull reflected the aggression and confidence of its commander – which was mirrored throughout the formation; unlike most of the other Volksgrenadier divisions, the 12th was highly experienced, efficient and possessed most of its authorised equipment.

Their role was to punch through the American lines along one of the routes assigned to elements of the 12th SS Division, through Büllingen towards Malmedy, working ahead of the panzers. Helmut Stiegeler of the 12th remembered the night of 15 December when he and his mates received a rare hot meal, and a bottle of schnapps each. Then they began to advance through the hills in the darkness. ‘The villages through which we marched lay peaceful in the December night. Perhaps a dog barked here and there, or people were talking and looking at the passing soldiers. Out of an imperfectly blacked-out window a vague light shone out. With all these sights, most of our thoughts were of home in our warm houses with our families.’

The third infantry unit under Priess was the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division under the bespectacled forty-eight-year-old Generalmajor Walther Wadehn; this was an old veteran unit that no longer contained any veterans. Completely destroyed in the fighting around St Lô in July and Falaise in August, its numbers had been made up with Luftwaffe ground personnel, like the 5th Fallschirmjäger Division further south. Most of the old jump-trained Fallschirmjägers, veterans of Crete or Russia, had already been sacrificed in combat and their replacements were relatively unfit with little understanding of ground combat. Photographs of the division in action show most of its men wearing the ordinary coal scuttle-shaped Wehrmacht helmet, rather than the signature cut-down Fallschirmjäger version, which indicated a veteran paratrooper and was only worn by the German parachute force.

Johannes Richter was a not untypical platoon commander in the 3rd Fallschirmjägers. He had enlisted as a twelve-year army man in 1932, but was transferred to the Luftwaffe at its creation, and served with the Condor Legion in Spain. He spent nearly ten years with a Fliegerhorst (aerodrome) Company, responsible for general supply, maintenance and guarding duties, reaching the rank of Oberfeldwebel. That easy life ended when he was transferred to a parachute school in September 1944, where his training lasted six weeks (without any parachuting), before being posted to the division on 11 November. Promoted to Fahnenjunker/ Oberfeldwebel (Senior Cadet Officer/NCO) in the 6th Company, Richter and his regiment were almost immediately pitted against the US 1st Infantry Division in the Hürtgen fighting, where he was wounded twice and his formation suffered 1,658 casualties in two weeks. Some of them were still in combat around Düren when the rest of the division transferred south for the start of Herbstnebel.

This is why the Sixth Army chief of staff, Krämer, assessed the 3rd Fallschirmjägers ‘at only 75 per cent strength’ on 16 December, an optimistic rating in itself, given they had no armoured vehicles (StuG assault guns) in their anti-tank battalion. Although Wadehn, its commander, had taken over back in August, his chief of staff was so clueless about land operations that Wadehn had to request his immediate replacement. By Null-Tag, only two of the division’s three regiments were assembled, with the third disengaging from the fighting in Düren. The Fallschirmjäger’s task was to dislodge the US 14th Cavalry Group from the Losheim gap, overwhelming it in the towns of Manderfeld and Holzheim, and opening up routes for the 1st SS Panzer Division.

While also controlling four army Nebelwerfer and two army artillery regiments attached for fire support, the undoubted mainstay of Preiss’s corps were his two crack SS panzer divisions, and the 501st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion (Schwere-SS-Panzer-Abteilung) of around thirty monster sixty-nine-ton King Tigers, although only half of the latter were fully operational on 16 December. Despite the ravages of war, ‘crack’ was still an appropriate word to describe the combat power and efficiency of the men and equipment they contained. The youthful Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, aged thirty-three, commanded the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte. He had joined the Nazi Party in September 1931 and been one of the original 120 members of Dietrich’s SS Watch-Battalion-Berlin, formed to guard Hitler’s Chancellery in March 1933. Mohnke saw action in France, Poland and the Balkans, and was eventually given command of a regiment in the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend.

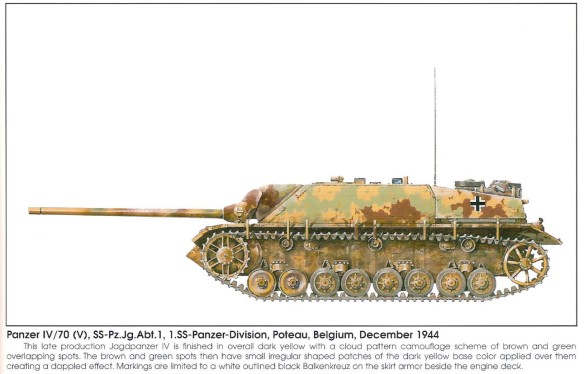

After leading his regiment through the attritional Normandy campaign, on 20 August Mohnke was awarded his original division, the Leibstandarte, which he would take to the Ardennes. Normandy had been in every way a killer for his division, from which no tanks or artillery returned at all; in a typical 1,000-man battalion only fifty escaped to fight again in the Ardennes. Yet, by December, it managed to boast a formidable complement of armoured vehicles and half-tracks. Its panzer regiment, led by Joachim ‘Jochen’ Peiper (one-time commander of der Lötlampe Abteilung, Blowtorch Battalion), a former adjutant of Himmler’s and recently recovered from wounds received in Normandy, fielded thirty-eight Panthers and thirty-four Panzer IVs. Along with the King Tigers, Panthers and Panzer IVs, the division’s anti-tank battalion boasted ten Panzerjäger IVs, a grand total of nearly one hundred tanks and tank destroyers, over 19,000 officers and men and nearly 3,000 vehicles.

It was in the Leibstandarte’s panzer regiment that Hans Hennecke served, leading a platoon of tanks from his mount, Panther No. 111, driven by Rottenführer Bahnes. ‘Peiper was the most dynamic man I ever met. He just got things done,’ Hennecke told me. ‘He was not much older than me, but seemed to belong to another generation. He was mature, spoke languages, was clever,’ Hennecke remembered, still in awe of his former comrade.

In 1944, according to Hans Bernhard, then a twenty-four-year-old Hauptsturmführer and Wilhelm Mohnke’s 1c (intelligence officer), their men responded to the ‘guiding principles of duty, loyalty, honour, Fatherland, comradeship’.

Duty. Honour. The Bulge gave rise to much debate about the brutality of Waffen-SS units towards American prisoners, and one commander consistently close to such accusations was Mohnke. On 28 May 1940, he had led an SS company which murdered eighty British prisoners of war at Wormhout, near Dunkirk. On 8 June 1944 his regiment was implicated in the killing of thirty-five Canadian prisoners in Normandy. We will never know how many Russians had disappeared under similar circumstances in the east. Carl-Heinz Bohnke remembered in Russia ‘We saw endless lines of prisoners. We couldn’t look after them. The later units did. We couldn’t.’

Oberst Bernd Freytag von Loringhoven (an Ostfront veteran who would command the Bundeswehr’s 19th PanzerBrigade in the 1960s) also recalled seeing ‘a line of Russian prisoners and a group of SS soldiers getting ready to shoot them. The SS sergeant said, “They’re just sub-humans, colonel”. And it was absolutely typical of the ideology that leaders in the Waffen-SS had told the simple man, the NCO, that prisoners of war without weapons were simply to be shot whenever necessary.’ The Russians themselves were already used to similar treatment from Stalin’s own thugs, but the consequences would be vastly different when organised murder met a democracy in war. It was this kind of unrestricted, premeditated horror, practised routinely by Himmler’s henchmen in Russia, which the Waffen-SS would bring to the Bulge. In short, murder and mayhem was the business of Mohnke and his men, as we shall discover shortly.

Such Nazi brutality was, and remains, beyond comprehension, except in one area. Ever since the RAF’s first thousand-bomber raid on Cologne of 30–31 May 1942, German soldiers and civilians had witnessed the terrible destruction of their own cities with consequential horrendous casualties, from which no one in the Reich was immune – except Hitler, of course, who refused to acknowledge or visit the stricken areas. On 16 November 1944 the city of Düren had been attacked by 485 Lancasters and thirteen Pathfinder Mosquitoes of the Royal Air Force. Sirens sounded and residents went down into the cellars. ‘When we emerged to clear up the mess, there was no mess to clear up because there was no town. There was just rubble. Düren was no more. The whole thing had taken about forty minutes,’ remembered one resident. Of 22,000 inhabitants, over 3,000 were killed and Obersturmbannführer Peiper and some of his men had been among those detailed to help rescue the survivors. After the war, the SS officer recounted how ‘the civilians had to be scraped from the walls’, and in response he swore he ‘would personally castrate the men who did that – with a piece of broken glass – blunt at that’. The Leibstandarte’s, and Peiper’s, viciousness could never be justified or forgivable, but the suffering of Düren, and other German cities, made it slightly more understandable.

Although Mohnke consistently denied he had issued orders to mistreat or murder captives, a similar pattern of deaths followed his military career wherever he served. In an organisation of thugs and murderers, with such ‘form’ Mohnke seems to have been near top in terms of nastiness. ‘After several years [of war] they were so desensitised,’ reflected Gerhard Stiller, a panzer commander with Mohnke’s division, ‘they didn’t even notice it any more. They’d bump someone off just like that. They had to develop humanity again, and that takes time.’ Perhaps Mohnke and his crew echoed the conversation that an army officer, Leutnant Freiherr Peter von der Osten-Sacken remembered with some SS officers, ‘who more or less told me, yes, things are pretty bad, but we have to win. We have so many bad things on our conscience that we have no choice but to hold out.’ Eduard Jahnke of the 2nd SS Das Reich Division admitted the same in a different way: ‘We were sure, we Waffen-SS men, they’d take no prisoners, just put us up against the wall. So it was “fight to the last bullet’’.’

The second armoured formation under Priess was Brigadeführer Hugo Kraas’s 12th SS-Panzer-Division HitlerJugend, which grew out of a cadre of the 1st SS Division in late 1943. Like his compatriot Mohnke, Kraas was born in 1911, joined the Nazi Party in 1934 and the SS the following year. He followed a similar career path in the Leibstandarte, fighting through Poland, France, the Balkans and Russia, but was wounded in January 1944 and missed the gruelling Normandy campaign which killed so many of his colleagues – the 12th left Normandy with 300 men, ten tanks and no artillery. It had commenced that campaign with a strength of over 20,000 men, many of them extremely experienced NCOs and veterans of Russia, and 150 tanks. Having recovered and passed a division commander’s course, Kraas stepped up to lead the 12th SS on 15 November when its former commander, Fritz Krämer, resigned to head Dietrich’s staff.

Assessed at 90 per cent strength in manpower and 80 per cent in equipment, on 10 December its Panzer Regiment included 38 Panthers and 37 Panzer IVs, the anti-tank battalion possessed 22 Panzerjäger IVs, while another 28 Panzerjäger IVs and 14 Jagdpanthers (‘hunting panthers’) served in attached formations, a total of 139 tracked, armoured vehicles. The forty-five-tonne Jagdpanther tank destroyer combined the 88mm gun carried in the Tiger I and King Tiger, with the excellent suspension and sloping armour of the Panther. Army Hauptmann Erwin Kressmann of the 519th Schwer Panzerjäger-Abteilung (Heavy Anti-tank Battalion) took his Jagdpanthers to the Ardennes, remembering, ‘With the enormous penetrating power of the eighty-eight we were able to effectively fight American tanks … We were able to let the enemy come fairly close, first of all because of our own armour and because of the strength and impact of the eighty-eight gun.’

Among the Panzergrenadiers serving in the 12th SS was Werner Kinnett, of Duisburg, who had turned seventeen in 1944. In April that year, two officers from the 12th HitlerJugend Division had arrived at his school and shown a propaganda film depicting various Waffen-SS heroes on the Eastern Front; they followed it with a recruitment talk, ending with ‘Raise your hand if you want to join’. They all did, some out of enthusiasm, others probably because of peer pressure. A couple had wanted to join a Wehrmacht unit; the recruiting officer cleverly warned them they must wait a further year, but the Waffen-SS would take them immediately. Werner asked if he should get his father’s permission, but the officer again had a ready answer: ‘If it’s alright by the Führer, then it will be alright by your father’. He joined the division in April 1944, and eight weeks later found himself on the Invasion Front at Caen, where he was soon wounded. He remembered that at the front other SS units got beer in rest areas, but the boys of his unit were given only milk. In hospital he was poached by an officer from the Das Reich Division and joined its Aufklärungs Abteilung (Reconnaissance Battalion), training in the Eifel in readiness for the Ardennes.

The nineteen-year-old Unterscharführer Hans Baumann, who would command a Hitlerjugend assault gun in the Ardennes, had already experienced combat with the Allies in Normandy. He observed: ‘We had already found out about the American army during the invasion. We were impressed by the high numbers of people and amount of matériel. We couldn’t keep up with that. You could be as brave as you wanted, but no soldier can endure that. We were simply overwhelmed by the vast amount of matériel. Even at that point our fight was basically already useless.’ Nineteen-year-old Bernard Heisig also fought in its ranks, recalling, ‘We didn’t like the name Hitlerjugend at all, as it made us sound like boys. We wanted to be real soldiers. The youngest ones weren’t given cigarettes. They didn’t smoke. They were actually given sweets instead.’

Dietrich possessed an even more powerful armoured formation, equipped with around 280 panzers, commanded by the victor of Arnhem, fifty-year-old Willi Bittrich. The history of the latter’s II SS Panzer Corps was a short and violent one. It included the 2nd SS Division Das Reich, led by Brigadeführer Heinz Lammerding, aged thirty-nine, who took command of his division on 23 October. It, too, was rebuilding after Normandy, where it was recorded as losing all but 450 men, fifteen tanks and six guns.40 Assessed at 80 per cent strength on 10 December, Das Reich fielded 58 Panthers, 28 Panzer IVs and 28 StuGs, with 20 Jagdpanzer IVs in the anti-tank battalion, totalling 130 armoured vehicles. Commanding a company of Das Reich’s Panthers was Obersturmführer Fritz Langanke, who at twenty-five had already been awarded a Knight’s Cross for his leadership in Normandy. He enthused about his mounts: ‘The Panther was the most functional and best tank in the world until the very end of the war. This was based on three components: velocity, cross-country mobility and tank protection. The Panther definitely achieved the best results in all three. The Sherman was an easy opponent for us. They could fire at us, but couldn’t penetrate our tanks. They had to come close within a few hundred metres to stand a chance.’

Bittrich’s second formation was the 9th SS Hohenstaufen Division, under the capable Brigadeführer Sylvester Stadler. The title came from a noble dynastic family who produced a number of kings and emperors in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The thirty-four-year-old Stadler, an Austrian, was another pre-war SS recruit who had fought in most campaigns prior to the Ardennes. In December 1944, the Hohenstaufen possessed 151 tanks and assault guns, distributed throughout the division: an impressive turnaround for a division reduced to 460 men, twenty-five tanks and twenty artillery pieces after Normandy, although it had fought more recently at Arnhem. Both the 2nd and 9th Divisions had followed the bloody trail of combat in Russia and Normandy and their few surviving officers and NCOs were very experienced indeed. With these two divisions, Bittrich’s strong corps was considered the most militarily professional in the Waffen-SS.

Full of young fanatics as all these Waffen-SS divisions were, in December 1944 it would not be correct to call all Dietrich’s men ‘true believers’. Until 1941 the SS was an entirely voluntary organisation, but after the invasion of Russia the original SS formations began receiving small numbers of Volksdeutsche replacements as the supply of German volunteers became exhausted. Serving under Jochen Peiper in the 1st SS Division, for example, was twenty-two-year-old Georg Fleps, tall, blond-haired and known as ‘a bit of a hot-head’; he was in fact a Romanian volunteer.

Although Himmler’s divisions still had the pick of Germany’s manpower, at the same time they began to rely on draftees, in competition with the army. Two of the last prisoners brought into American lines before 16 December were from the 12th SS Division. One had stepped on a mine and caused quite a stir among the US medics treating him, as their first SS casualty. The second, unwounded, prisoner was Polish, recently drafted into the SS from a part of western Poland absorbed into the Third Reich. He and his mate were far from home, had no wish to fight the Americans and wished to desert, hence his friend colliding with a shu-mine in no man’s land at night. Both Hitlerjugend Division conscripts recounted a story to the medical staff, delivered via an interpreter, of how their division were assembling opposite for an attack, using searchlights to illuminate their advance, which – sadly – was not relayed to VIII Corps headquarters as the divisional intelligence officer concerned wished to talk personally with the prisoners.

By 1944, it had become commonplace for Luftwaffe and naval personnel to be reassigned to the Waffen-SS, without any say in the matter. Although he did not fight in the Ardennes, the German writer and future Nobel Prize-winner Günter Grass was typical of this latter group, applying to join the submarine force on his seventeenth birthday in 1944, but on rejection was drafted into the 10th SS Panzer Division instead. Among numerous others in Kampfgruppe Peiper, for example, Rottenführer Heinz Schwarz, commander of a half-track in the 2nd SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment, was one of many in the formation to have been forcibly transferred from the Luftwaffe that summer.

In the Ardennes, out of 150 personnel in one sample company of the Leibstandarte (10th Company of 2nd SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment), 10 per cent were Normandy veterans, 15 per cent came from the Luftwaffe (aged between eighteen and thirty), and 60 per cent were seventeen-year-old youths, all born in 1927, drawn straight from the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD), who had received at most three weeks of training. The remainder were new recruits from a variety of backgrounds with different levels of training. Himmler’s desperate drive for recruits in 1944 – whether into the Volksgrenadiers or the Waffen-SS – had completely broken the system for recruitment and training in the Reich. In overall terms, of all the military recruits born in 1928, some 95,000 (17.3 per cent) were drafted into the SS. Few of these had received any meaningful military training, yet they made up the bulk of manpower within the SS divisions in the Ardennes. A GI on the receiving end may have viewed these statistics in a different light – each one would have seemed a potential killer – but youth and enthusiasm alone do not make a soldier.

This analysis is very much at odds with that of Hugh Cole, who in the US Army Official History of 1965, wrote, ‘The 1st SS Panzer Division … was the strongest fighting unit in the Sixth Panzer Army. Undiluted by any large influx of untrained Luftwaffe or Navy replacements, possessed of most of its T/O&E [Table of Organisation and Equipment], it had an available armored strength on 16 December of about a hundred tanks, equally divided between the Mark IV and the Panther, plus forty-two Tiger tanks belonging to the 501st SS Panzer Detachment.’ Cole was writing from the best available data twenty years after the Bulge, but far more detailed information has surfaced since then.

Given that the Volksgrenadier infantry divisions were composed of many similar individuals, what set the SS divisions apart? It was the effort made to teach these new recruits, whether volunteers or conscripts, ex-Luftwaffe or Kriegsmarine, that they were an elite. Training times were ludicrously short, and the men themselves were not always as enthusiastic as the earlier, more impressionable youngsters, but veteran soldiers and NCOs were sprinkled at every level in all units, specifically to engender the SS ethos. The cavalry officer Philipp von Boeselanger realised, ‘They almost took it for granted that they would die; but they were also brutal in their killing’, while Rottenführer Jürgen Girgensohn later mused, ‘In retrospect I believe there was a strong esprit de corps based on a common attitude. We were convinced it was a just struggle and that we were a master race. We were the best of the master race – that does unite people.’

However, this much is also clear: all the four SS panzer divisions were a shadow of their former selves in terms of personnel and equipment, when compared to the same formations that had fought in Normandy just six months earlier. Himmler had restored their numbers, but the replacements were immature, lacked experience and in some cases had received no meaningful combat training whatsoever. Whatever they were, they certainly weren’t superhuman. Some of the Waffen-SS troopers who fought in the Bulge were undoubtedly brainwashed thugs and fanatics, but many were ordinary conscripts, new to war and caught in a brutal system.