Hitler envisaged the star turn of his Ardennes offensive to be the Sixth Panzer Army, an entirely new creation. That it was to be led by the Waffen-SS’s senior field commander, and contain four SS panzer divisions, was no accident. This was another of the Führer’s responses to 20 July: thereafter the only organisation with which he felt safe, on which he could rely, was Himmler’s SS. Heinrich, Graf von Einsiedel, a great-grandson of Otto von Bismarck and a young lieutenant in 1944, observed, ‘The generals kept on assuming that the army was the only arms-bearer of the nation. But it was quite clear that another force was being built up that wanted to compete with the army for power’. It was almost as though Hitler built the Ardennes offensive around the capabilities of his Sixth Panzer Army, created expressly for the purpose on 14 September 1944 and bulging with SS troopers, rather than the force being harnessed to Hitler’s master plan.

Obersturmführer Hans Hennecke, wasa tank commander who had served in Russia, Normandy and the Ardennes. Born in August 1920 in the northern spa town of Waren, Hennecke spent his spare time in the HitlerJugend while at school, and after six months compulsory service in the Reichsarbeitsdienst he volunteered for the Waffen-SS. ‘I was lured,’ he remembered, ‘partly by the snappy black uniform and also by recruiting posters.’ The clothing was designed by the fashion consultant Hugo Boss, and the posters were the work of Ottomar Anton, an SS officer who produced pre-war art deco-style travel advertising for the Hamburg-Amerika, Cunard and White Star shipping lines and the Berlin Olympics. By using top designers, the Nazis showed an appreciation of the importance of branding and image, which appealed domestically to millions of Germans like Hennecke, and overseas to many who frankly sympathised with Germany’s ideals, at least until war came.

He was immediately accepted, volunteering just as the Waffen-SS had started to expand following the fall of France; with a possible invasion of England looming, they needed to fill their ranks. Pre-war volunteers for the SS had to be perfect physical specimens, to show proof of pure Germanic ancestry back to 1800, while those who became officers had further to demonstrate their ancestry to 1750; all signed on for an initial period of four years, but under wartime conditions all these requirements were gradually relaxed.

‘Our training,’ Hennecke remembered, ‘stressed three points: physical fitness, weapons proficiency and character. Our days began at 06.00 a.m. with a rigorous hour-long physical training session, a pause for a bowl of porridge, then intensive weapons training, followed by target practice on the ranges and unarmed combat lessons. We continued after a hearty lunch with a drill session, followed by cleaning duties and finished off with a run or a couple of hours on the sports field.’ He thought it was ironic that he spent relatively little time on drill and more on tactics, because the unit he served with, the Leibstandarte, ‘originated as Hitler’s personal body guard and, spending most of their time on the parade square, had acquired the derisory nickname of asphaltsoldaten (asphalt soldiers)’. Nevertheless, thanks to athletics and cross-country running every day, Hennecke and his SS comrades developed levels of fitness and endurance enabling them to cover half a mile in full kit in twenty minutes, which far surpassed the requirements of conscripts in the Heer, the German army.

On qualifying as an SS-Schütze (private), Hennecke and his class were awarded their SS walking-out daggers during a ceremony at the Feldherrnhalle Memorial in Munich. This annual ritual, steeped in mysticism and intended to reflect the traditions of medieval Teutonic knights, was held each 9 November, the date of the unsuccessful putsch of 1923 (and later, ominously, of Kristallnacht). Etched on his dagger’s blade, he remembered, was the SS motto, Meine Ehre Heisst Treue (My Honour is Loyalty). On 20 April (Hitler’s birthday), they had each taken their oath of loyalty to the Führer.

After gruelling service in the ranks in Russia, Hennecke was selected for officer training and sent to a Junkerschule in 1943. The Waffen-SS offered advancement to promising candidates regardless of their education or social background, and named their academies Junkerschulen (schools for young nobles). ‘We were even issued an etiquette manual that included a chapter on table manners,’ he recalled. ‘In the middle of the war we were being taught “champagne glasses to be parallel to the third tunic button, arm extended at forty-five degrees, white wine to be drunk from tall glasses, red from short”. I’ve never forgotten that … In the middle of the war!’ Hennecke broke off, shaking his head in mirth. ‘Off-duty, officers and men were obliged to address each other with the classless title of “Kamerad”, as you would say “mate”, or “buddy”. We were forbidden padlocks on our lockers to build the mutual trust necessary in a combat unit, whilst unconditional obedience was required at all times. Such obedience was embodied in the term Führerprinzip (leader principle), which essentially meant that Hitler’s word was above all written law and therefore refusal of orders from him or his delegates was not an option.’

Evening sessions concentrated on Nazi ideology, the evils of Bolshevism, Aryan genealogy and Nordic mythology, all now exposed as bogus. Hennecke observed of those times, ‘we lapped it up, knowing nothing else’. They had to study Hitler’s book Mein Kampf, and he recalled that during his five-month course, one officer candidate in three was rejected for failing the ideology examination. Simultaneously, field exercises were designed to turn Hennecke and his generation into not just leaders, but an elite. Even before the war, SS schools were producing more than 400 officers a year, but by 1942 nearly 700 Waffen-SS officers had been killed in action, and Hennecke remembered fellow officer candidates from several occupied countries. Most foreigners who volunteered for service in the Germanic legions enlisted to fight Communism, but still had to be able to prove Aryan descent for two generations, and to possess a ‘good’ character, whatever that meant by SS standards.

Leadership training groomed them to notions of individual responsibility and military teamwork. At the heart of Waffen-SS doctrine, reinforced by Russian Front experiences, were combat concepts born of the final year of the Great War, when Sturmtruppen (elite storm troop units) were raised and trained for trench raids. Here, the need for speed, shock and surprise was paramount, all of which required strong leadership skills, the ability to employ initiative when circumstances dictated, and exhaustive training to be able to use any weapon, fight at night and cope with being surrounded and cut off. Leaders were trained always to take immediate, aggressive action, counter-attack without thinking and induce fear in the enemy. Such Great War combat was unconventional and necessarily ruthless, employing knuckle-dusters, trench knives and bayonets, grenades and entrenching tools with edges sharpened to razors. Under these circumstances the taking of prisoners was often regarded as an inconvenience.

Though the scale and technology had changed from 1918, such extreme ruthlessness and fitness, when fused with ideology, made the Waffen-SS a lethal opponent. Taught to believe that the Russians were subhuman and that they were embarking on a crusade to save Western civilisation, Hennecke and his colleagues were indoctrinated to achieve victory at whatever cost. On the Eastern Front, Hennecke remembered his battalion’s motto, Wir nehmen Tod, Wir teilen Tod Aus (We accept death, we hand out death). Nearby in Russia, he reminisced, was a unit (III Battalion of the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment) which acquired the nickname of der Lötlampe Abteilung (Blowtorch Battalion) because of the speed with which they burned through Soviet formations and torched villages. Such concepts the Waffen-SS brought to the Western Front and would employ against their American foes in the Ardennes: they knew no other way.

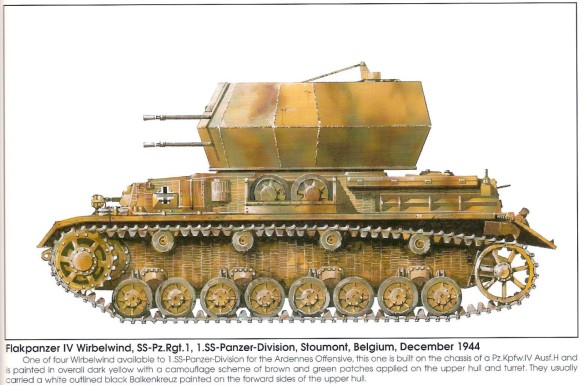

Hennecke could still recite his SS serial number (363530), and proudly recounted that by 1944 he had become a seasoned veteran of the Russian Front, won the Iron Cross, gained a commission and was commanding a tank platoon in the 1st SS Panzer Regiment. He proved very adaptable and served as a platoon leader (Zugführer) of tank, anti-aircraft and combat reconnaissance units, which was his role when an Untersturmführer in an SS Kampfgruppe during the Battle of the Bulge, aged twenty-four.

Hans Hennecke’s story was typical of many ‘true believers’ in the formations which comprised Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army. The potential presence of Dietrich, as we have seen, greatly worried Allied intelligence because of the unique reputation he had accrued to this date, for he was no ordinary military commander but one of the original Nazis. In contrast to the younger and immature Himmler, he was a colourful character, said to be ‘larger than life’ and one of the closest men to Hitler, who had won over many contemporaries with his sheer military competence during the Second World War; Rundstedt called him ‘decent but stupid’. His several biographers agree that his rise to prominence was not necessarily due to Nazi fanaticism, acceptance of unsavoury National Socialist racial policies or political beliefs, but from blind, stubborn loyalty, as well as tactical military skill. Perhaps Hitler identified with the mustachioed, stocky, five-foot-six Bavarian ex-sergeant-major, with blue eyes and brown hair, who had a strong, square jaw and spoke with a broad accent. By all accounts, he was extraordinarily brave, had an infectious sense of humour and enjoyed his drink.

Possibly aware he was overpromoted, Dietrich relied heavily on his chief of staff, Fritz Krämer, a former Wehrmacht officer, to run his command on a day-to-day basis, while – ever the sergeant-major – he spent time with his troops, for example visiting tank repair workshops where he distributed Iron Crosses to the mechanics who kept his panzers on the road.6 Although Dietrich was liked by many non-SS personnel, the panzer staff officer Oberst Bernd Freytag von Loringhoven observed, ‘We weren’t impressed with his talents as a commander. He had no prior training at all. He’d been a sergeant in the First World War and after that he never had any kind of advanced military training whatsoever.’ The Jesuit-educated cavalry officer Oberstleutnant Philipp Freiherr von Boeselanger (who with his brother was part of the Stauffenberg circle of plotters) agreed: ‘Dietrich had a strange way of giving orders. I heard several of his during the war. He’d say “You attack this, you that, then sort it out”. It wasn’t the way we gave orders in the army, with clear aims and limits and so on. His method was simply “Well do it this way. You left, you right”.’

The final instructions for Herbstnebel issued to Dietrich and Krämer renamed their command the innocuous-sounding Auffrischungstab 16 (Refurbishment Staff No. 16), in a final attempt at operational deception (Manteuffel’s Fifth Army was similarly retitled as the meaningless Feldjäger-Kommando z.b.v) – though Bletchley Park saw straight through these half-hearted ruses. Model’s orders, issued via Rundstedt’s OB West headquarters, were that they should ‘break through the American front to the north of the Schnee Eifel, and resolutely thrust forward with their fast-moving units [i.e. panzers] on their right flank, towards the Meuse crossing points between Liège and Huy, in order to capture these in conjunction with Operation Greif [Skorzeny’s commandos]. Following this, Sixth Panzer Army will drive forward to the Albert Canal between Maastricht and Antwerp … As soon as the Sixth Army has secured the Meuse crossings, this defensive flank will be placed under command of Fifteenth Army. Operation Strösser will be carried out with 800 paratroopers at 07.45 a.m. on Null-Tag … should this operation [Strösser] not take place because of unfavourable weather conditions, it will take place 24 hours later …’

Privately, Dietrich felt the plan was doomed, but his political nose had taught him to keep his reservations to himself and do what he was told. In a famous September 1945 interview with the Canadian intelligence officer Milton Shulman, all Dietrich’s tensions about the offensive bubbled to the surface, with Shulman witnessing him flinging out his arms and puffing out his cheeks. He was under investigation at the time for war crimes against murdered GIs; nevertheless Shulman recorded Dietrich’s outburst, expressed in the following dramatic terms:

‘All I had to do was cross a river, capture Brussels and then go on and take the port of Antwerp. And all this in December, January and February, the worst three months of the year; through the Ardennes where snow was waist deep and there wasn’t room to deploy four tanks abreast, let alone six armoured divisions; when it didn’t get light until eight in the morning and was dark again at four in the afternoon and my tanks can’t fight at night; with divisions that had just been reformed and were composed chiefly of raw untrained recruits; and at Christmas time.’ The crack in Dietrich’s voice when he reached this last obstacle made it sound like the most heartbreaking of all.

We have to take it at face value that these were Dietrich’s private thoughts at the time, and there seems no reason to doubt the victor of endless fights under mountains of Russian snow in much worse sub-zero conditions. Hitler’s favouritism towards the SS was reflected not only in the strength and equipment of those individual units committed to battle, but in the size of Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army itself. With five infantry and four panzer divisions distributed over three corps, plus substantial artillery, Nebelwerfer and engineer units, the formation was the size of Fifth and Seventh Armies combined, and clearly designed to be the Schwerpunkt, or main effort. He had nearly 700 tanks, tracked tank destroyers and assault guns at his disposal, 685 artillery pieces and 340 Nebelwerfers.

None of Dietrich’s infantry divisions belonged to the SS, although they came under his command for the offensive. In contrast to Manteuffel’s approach in the Fifth Panzer Army’s sector, of advancing on a wide front on the basis that ‘if we knock on ten doors simultaneously, several will open’, Dietrich and Krämer proposed to move along narrow attack corridors, echeloned in depth, which the Fifth Army commander felt inappropriate in the treacherous Ardennes region with its poor roads, numerous rivers and challenging terrain.

Manteuffel argued with much logic that such a tactic offered endless opportunities for the ardent defender to slow down his attacker with well-sited roadblocks and ambushes. The baron would prove correct, as did his map appreciation of the Herbstnebel battlefront. Sixth Panzer Army, with the most powerful forces, had been allocated the most difficult terrain. It would not matter how much combat power Dietrich possessed; if the Americans chose to block him, there was no power in the Reich that could force a passage through what was termed the ‘northern shoulder’. Manteuffel argued with great foresight in December 1944 that just a little of Dietrich’s combat power transferred south to Brandenberger (who had no tanks and too few bridging units) and to his own Fifth Army would yield much greater opportunities than being stuck in traffic jams north of the Schnee Eifel. This was not sour grapes; hindsight has proved Manteuffel right.

Dietrich’s Sixth Army included three corps, only two of which were staffed by the Waffen-SS. The exception was that of Generalleutnant Otto Hitzfeld, bearer of the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, five times wounded and known as the ‘Lion of Sevastopol’ for his victory there in 1942. He had taught infantry tactics at the Infantry Kriegsschule in Dresden alongside Rommel in the 1930s, later commanding units in France and Russia, before being appointed to lead LXVII Corps on 1 November. Then forty-six, Hitzfeld commanded two horse-drawn Volksgrenadier divisions, whose appearance was in total contrast to the usual image one might have of an SS panzer army.

Knight’s Cross holder and Eastern Front veteran Oberst Georg Kosmalla commanded the 272nd Volksgrenadiers, which had been engaged in heavy fighting against the American 78th Division in the Hürtgen Forest.12 One of his officers, Leutnant Günther Schmidt, a survivor of the original 272nd Division which had been badly mauled in Normandy, returned to Germany as the only officer left in his battalion. His experience of preparing for Herbstnebel was like that of so many other junior leaders: ‘Every day more newcomers came; many in grey-green Kriegsmarine uniforms, or in the blue-grey of the Luftwaffe. Most of them had only short and insufficient training.’

Another Normandy survivor was Obergefreiter Otto Gunkel of the 981st Volksgrenadier Regiment, who remembered the replacements, ‘well-fed guys equipped as if it was peacetime, and who were not very happy about a duty as infantry. They had first to resign themselves to their fate and then they would become good and loyal infantrymen’. In overall terms, Kosmalla’s division, recalled Schmidt, included about 20 per cent skilled infantrymen and the rest were former Kriegsmarine or Luftwaffe personnel. On 30 October they boarded a train in the dark heading westwards; at Cologne they stopped while an air raid was in progress. ‘The train stopped between houses, no one was allowed to get out of the train. The Flak started to shoot and some bombs fell in the distance.’

Echoing the experience of the US 4th and 28th Divisions, the Hürtgen soon reduced the much-battered 272nd Volksgrenadiers to a ‘sad little group of tired soldiers, with dirty, unshaved and torn uniforms, one third of our original strength,’ remembered Obergefreiter Gunkel. ‘Our company HQ detachment had only four men. Both our heavy-machine gun platoons were decreased to squads. The 5th company was wiped out – wounded, dead, or taken prisoner. This was the horrible result of only ten days in the Hürtgen Forest, even higher losses than during the first ten days in Normandy. I walked behind the horse-drawn cart that was loaded with our dead of the day before.’ As they withdrew from the Hürtgen to prepare for Herbstnebel, Gunkel saw that the woods around Gemünd and all the other small villages were full of soldiers from newly arrived units.

‘These men were well equipped with winter camouflage uniforms, winter-boots, fur-hoods, etc. Long convoys of armoured vehicles, assault guns and artillery were standing along the roads. But we did not then know that these troops were preparing for the Ardennes Offensive.’ Arriving after the Hürtgen was seventeen year-old Grenadier Andreas Wego, apprenticed to a mason by trade, who was inducted into the Kriegsmarine in July 1944 for three months’ basic training. This included ‘half-mile forced marches with a sixty-pound pack and combat gear while wearing a gas mask, followed by classroom training back at the barracks’. At the end of September, when he received his last monthly naval pay of 30 Reichsmarks, his whole class was transferred into the army and the 272nd Volksgrenadiers. He then had a month at the divisional battle school near Berlin before heading for the front in November.

Many histories of the Ardennes campaign have alleged the Germans were better-equipped and trained than the opposing US forces. Here is evidence which suggests a different overall trend. German infantry divisions in the Bulge were in nearly every case inferior to their American counterparts and some, such as the 272nd Volksgrenadiers, had already taken huge casualties in the Hürtgen, with a consequent effect on morale.

General Hitzfeld’s other division was the 326th Volksgrenadiers, reformed from another formation annihilated in Normandy and partially containing ethnic Volksdeutsche from Hungary. It was commanded by Generalmajor Dr Erwin Kaschner, who had been captured by the British in the First World War and served in France and Russia from 1940 to 1943. His division was originally slated for Manteuffel’s Fifth Army, but due to its lack of mobility (it was 400 horses short), it was transferred to the Sixth for operations to protect Dietrich’s right flank, where there was less call for movement. Both the 272nd and 326th Volksgrenadiers had a largely static role, not unlike Brandenberger’s Seventh Army in the south, of seizing the high ground of the Elsenborn Ridge and protecting the flanks from counter-attacking US divisions.

Gelinenkirchen-born Josef Reinartz was a twenty-eight-year-old platoon commander with the 326th in the Ardennes. He had been conscripted in 1938, seen action in France where he was wounded, and Russia where he survived the awful 1941–2 winter before being discharged with severe exhaustion and the effects of frostbite (missing toes) in June 1942. Reading between the lines, his discharge may also have been connected with combat stress (PTSD). He worked on the Deutsche Reichsbahn as a locomotive engineer until being recalled to the colours in September 1944 under Himmler’s recruitment schemes. He was attached to the 753rd Volksgrenadier Regiment and moved to the front with his unit on 26 November, being promoted Unteroffizier on 1 December. Combat experience like his – Reinartz had been awarded an Iron Cross and Infantry Assault Badge in Russia – would make a huge difference in the coming days.

Another Landser in the 326th was Alfred Becker of Köln, a twenty-year-old Gefreiter, who still sports a purplish-red letter ‘A’ tattooed on his left shoulder blade because ‘my Erkennungsmarke (dog tags) omitted to indicate my blood group, so I had it done on my shoulder’. In the Ardennes, Becker wore ‘an overcoat with a Kopfschutzer (toque), mittens with a trigger finger and a sweater with a high neck. Some in our division had camouflaged snow suits.’ At the front, Becker smoked a pipe, observing, ‘pipes were popular with young men back then. They were better for the front lines. You can see a cigarette burning and so they tend to draw bullets to your face. This is not good for your teeth.’ Becker carried a carbine and a smoke grenade. ‘The smoke grenade was to hide you if you wanted to attack or get away. Later on, when I became the squad leader, I carried a sub-machine-gun.’ He remembered of his days in the Ardennes, ‘We thought we could beat the English and Americans in a fair fight, but they had more matériel than we did, so the fights were very uneven. If you shot at an American infantry unit, they would blow you to bits with bombs or artillery shells. This was very frustrating. The Americans were very spoiled. Lots of good food, good clothing, nice boots. But they were very humane.’

Despite the fact that Hitzfeld’s LXVII Corps mission was to help clear the way for the 1st and 12th SS Panzer Divisions, then contain the ‘northern shoulder’ of the Bulge, his two divisions wholly, or in part, would fail to achieve even that. Due to the unexpected US V Corps (78th and 2nd Divisions) attack to reach the Roer dams on 14 December, some of the 326th Volksgrenadiers would be tied down fighting the US Army at Wahlerscheid. At the same time, Kosmalla’s 272nd Division, also embroiled in the same battle, were likewise too preoccupied to shift south and take a full part in the Ardennes assault. Both found themselves fighting hard to retain the village of Kesternich because it was a transit point for Herbstnebel units heading south for the concentration areas in the Eifel. Though the pressure on the Germans eased on the days after 16 December, when the US V Corps withdrew south to aid their comrades, the damage had been done. Hitzfeld’s divisions had been unable to contribute to the start of the Ardennes attack, besides losing badly needed personnel. The failure of Hitzfeld’s corps to support Sixth Panzer Army was not his fault, but further evidence that Hitler had thrown together his Ardennes plan without any real reference to what the US Army might do to thwart him.