As in no other air war in recent history, the Korean War was fought by opposing combatants who had no stake whatsoever in the territory in dispute. When the North invaded the South, Americans entered the battle openly and with heavy commitment. The Soviets elected to go undercover with limited aid in material and especially in manpower. For whatever reason, neither side expressed a specific goal or objective, other than to fight one another and to hopefully bring the whole sad affair to an end. Unfortunately, the war never officially ended. In spite of over a half century of negotiation, neither side has surrendered or agreed on a formal truce to end the armed conflict. Instead, both sides signed a tenuous cease-fire agreement and technically the combatants remain in a state-of-war.

By the end of October 1950, the Korean and Chinese aviation assets had been combined into a single Unified Air Army (OVA) to protect a limited number of rear area resources. Short of equipment and lacking combat experience, they were unable to overcome UN air superiority and fulfill even this limited role. It soon became clear that unless the Soviet Union became involved, the Americans and their Allies would dominate the skies over Korea.

In November 1950, Lt. Colonel Alexandr Pavlovich Smorchkov was flying a MiG-15 when the commander of the Moscow Air Defense, General Colonel K. Moscalenko, informed him that he was to initiate “Polikarpov Po-2 in Flight,” a top-secret deployment. Without delay, Smorchkov’s regiment boarded a secret night train to travel to the Far East to fight in the Korean War. Days later, the Soviet 64th IAK (Istrebitel’niy Aviatsionniy Korpus or Independent Fighter Aviation Corps), arrived at their destination, greeted by tropical downpours so heavy that ducks were swimming on their airfield.

The regiment first operated from the airbase at Mukden. A few days later they transferred to Antung Airbase where they joined other regiments. The primary mission of Smorchkov’s regiment was to protect the bridges across the Yalu River and the Antung power station, which supplied electrical power to North Korea.

In his autobiography, In the Skies of Two Wars, Sergey Makarovich Kramarenko details his experiences as a MiG commander in the 176th Regiment from March 1951 until early February 1952. The Soviet involvement, he wrote, came as a complete package that included not only fighter units but also anti-aircraft artillery, air traffic control, communications, and support. In December 1950 the 28th IAD (Istrebitel’naya Aviatsionnaya Diviziya or Fighter Aviation Division) was relocated to Xingdao to train Chinese and Korean jet fighter pilots. The Russians implemented rigid training in air-to-air and air-to-ground combat. They also increased the number of radar and visual observation posts in the air defense network. While part of the OVA went out to destroy UN bombers before they reached their targets, reserve units were assigned to repulse surprise attacks and cover the landing of their own aircraft. Aircraft were dispersed and concealed, and organized for quick turnaround and takeoff.

Given the magnitude of their mission, one would assume that the logistics of supporting a brand new jet fighter in a combat environment at so great a distance from the source of supplies would be insurmountable. Although various reports written at the time suggests that the Soviets periodically ran out of fuel, ammunition, and most of the other materials necessary to conduct a successful combat operation, when queried, the pilots of the 64th IAK could not recall ever having to cancel a combat sortie because they lacked airplanes, spare parts, ammo, or fuel. The only materiel shortage mentioned in Russian archives was a lack of drop tanks in November 1950. This forced Soviet fliers to retain them except when under attack, and limited maneuverability when they were attacking UN bombers. The problem became more critical as the distance to the combat zones over Uiju, Sinuiju, and Sonchon increased. When Soviets moved their aircraft forward to Antung, wing tanks ceased to be a major problem because of the decreased distance to the combat zone,.

Although materiel support is not generally acknowledged to have been a serious problem, between November 1951 and January 1952 the 303rd and 324th IAD ran short of an even more important commodity, pilots. This was due in part to combat attrition and in part to illnesses. To make matters worse, the replacement pilots that arrived in early November were, in Kramarenko’s words, “rookies”. While most of Kramarenko’s pilots were WWII veterans with over three hundred hours piloting jet aircraft, the replacements had only 50-60 hours in jets and little combat experience.

Feelings among the older pilots of the both Soviet combat divisions were that General Yevgeny I. Savitskiy, Commander of Fighter Aviation and Anti-Aircraft Defense (and one of Stalin’s favorites), felt envious of their successes in the Korean theater. Much like their US counterparts, who glorified competition between the Army and Navy, and more recently the Air Force, the Soviet military thrived on competition between the VVS and the PVO. By sending rookie replacements to the elite 303rd and 324th IAD, their success rate was sure to suffer and provide General Savitskiy with a valid argument to replace them with divisions of his own force, the 97th and 190th IAD. Whether this was fact or rumor has never been ascertained.

In his book, Neizvestnaya Voyna (The Unknown War, translated by Stephen “Cookie” Sewell) veteran 196th IAP MiG pilot, Captain Boris Stepanovich Abakumov describes what everyday life was like for the Soviets in far-off Manchuria:

“We ate at a mess hall. For the first few days we only had Chinese cooking to eat. Their dinner consisted of 7-8 courses, but all of them were simple. They made them very tasty, and we had many different dishes on the table but their portions were very small, and after dinner we were still somewhat hungry and wanted just a bit more to snack upon. For example, the course portion of roast potatoes amounted to five large spoonfuls of potatoes and that was it. That was the way with every course—well prepared and tasty but skimpy. Chicken was dark gray, since we only got it several days after we requested it for our table, but we could see that it was cured and then even the legs were cut into several pieces. The same sort of thing happened with veal medallions. Veal was cut up and cured by medallions. This habit was odd to us (and) was why the chicken had such a strange color—curing was no different than the same method the Chinese used to cure pork. Frequently we could hear the “squeals” of pigs from the village near our garrison. These were not pleasant to hear. We asked ourselves, ‘What’s the matter?’ It turned out that this method was the way that they drove the ‘evil spirits’ out of the pigs… The command, noting our insufficient provisions, moved to have food prepared by our cooks … The Chinese cooks were stunned to see the size of our portions, which we freely devoured. They began to shake their heads and click their tongues. Of course, none of them had to fly jet aircraft (in) combat. We needed high calorie chow, or we would not be able to handle the stress.

“We had two ‘mustachios’ in our regiment, that is, two men with large mustaches. They were Volodya Alfeyev and Lev Ivanov. Each of them had a personal score of ten victories … and they had been recommended for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union… I also had a mustache up until I could not get it to fit under my oxygen mask in flight, and as a result I had to trim it back. But these boys would not shave theirs off until our combat tour was over… (and) brought great delight to the local residents, who could seldom get them to “sprout” on their faces. Their admirers attempted several times to grow a mustache, which brought about lots of exclamations and head bobbing in some kind of clattering language. On occasion one of them would begin to sprout a mustache and the ‘attention’ would fall on them, and they, completely satisfied, would begin to move with outthrust jaws, supposing that they now had a sting in their arms. This would bring out gales of laughter… We had our own ringleaders, as one has in any collective. Lev Ivanov was one such ringleader, as he was an outgoing, sympathetic comrade. He had a lot of different facetious sayings, which he was perfect at choosing the time and place to say them… It was no accident that he loved to play chess, too … the games often took on a merry nature, if one of the participants was Aleksey Ivanovich Mitusov, who… played chess in every free moment that he was not in the air, and frequently bantered with his partners …

“We occasionally got movies at the airfield, which we would play when we went down into the bomb shelter. The greatest hunter we had—Vasya Fukin—would do his best between flights to bag ducks with a shotgun. This is how we kept up our normal routine. The pilots were enterprising and cheerful people. During the rains, when the airfield flooded with water from the ‘opening of the heavens’ and the pumps were not able to get it over the berms, the fishermen among us would then carry out their skills. Using just their hands they would catch rather large fish, like you see in the cowboy movies, but it was unknown how they got into the deep basins that fed the pumping stations.

“We received a 30% bonus, which we dubbed ‘field money’ as it was paid in local currency, and which we could use to purchase various items in a specialty store in the village. We attempted to turn our mess hall into a local hall with everything there. Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub (CO of the 324th IAD, top allied WWII ace with 62 aerial victories) and his assistants also ate here in this hall.

“Once Ivan Nikitovich was walking among the tables in the mess hall when he spotted Sasha Litvinyuk sitting rather sadly. Kozhedub went up to him and asked, as he placed his hand on Sasha’s shoulder, what was bothering him and what he could do to make things better. During the conversation, which we recall to this day, Sasha will always recall the warmth of the conversation with him.

“Eight men sat around our round table. We ate here in the mess hall twice a day, (first, breakfast) in the mornings long before dawn, when there was no hint of sunlight. We would pour down cups of coffee or cocoa; eat bread covered in pear butter and cookies or chunks of chocolate bars. Before dawn we just had no appetite for any other food.… In the evenings, after our missions, we could safely eat hearty meals: up to two portions of meat and two portions of vegetable, and then after some great warm Siberian dumplings, of course, we would receive 100-150 grams of spirits. At the mess hall we each received a bottle of beer, and also a bottle of cognac or port wine. But, as we held ourselves to account, nobody ever exceeded his limit. We still held this though: at home we kept full bottles, but here they would remain in the mess hall. And functionally everyone knew that tomorrow the combat missions with their great stress on the body were coming, and nobody wanted to fail to make correct reactions in a complicated aerial situation.

“Korean and Chinese pilots frequently ate with us, so that they got to eat our food, and not just rice. They knew how to fight well in combat; their rations just would not support them. On occasion we would also invite them to eat our hearty meals as well as to share our cognac. After lights out the flight personnel went to sleep, but the technicians and service personnel went to watch movies.

“About 0900 hours we would have breakfast at our airfield. After breakfast almost nobody was relaxed. The same happened with dinner. Before a mission you just lost your appetite. The Americans specially organized their raids to coincide with our meal times (assumption probably not true—author). They knew that carrying out high stress maneuvers with a full stomach created a very large weight on the body, and subsequently shifted the center of gravity, and that had a negative effect on health and self-awareness; therefore, we consumed the majority of the calories we needed at supper, and got the ‘combat ration’ of one hundred grams to settle our nervous system down. This helped us quickly fall asleep. On occasion we would go over and pick up some vodka from the store and just before supper drink it with a small group of comrades. This was a forbidden situation, as they say, which we did on the run like swiping apples from a tree. But I have no idea why this was accepted, as we kept the bottles quite openly on our tables, free for all who shared the same spirit. Of course, even after such a procedure at your table in the mess everyone remained pretty close to sober. No one demanded you stay close to the norms. It was more a fact of strict self-control. Perhaps there was some sort of psychologically thicker side to the required amount of spirits you could intake with a narrow circle of comrades.”

Abakumov recalled that the area around the air bases at Antung, Myaogou and Dapu in China contained numerous fruit orchards. At the right time of year the pilots would find baskets full of fruit at their tables and during their free time between flights, some pilots picked fruit for themselves.

Boris Abakumo piloted a MiG-15 in the battle on 12 April 1951, and probably shared the shootdown of the B-29A # 44-62252 with his buddy Boris Obratsov. Later, on 21 July 1951, he also downed the F9F-2 of Lt. Richard W. Bell and damaged Kenneth H. Rapp’s F-86A on 27 September 1951.

Although one might assume that Chinese rations would be insufficient for the Russian appetite, the pilots say they always got enough food and considered their rations more than adequate, even though they believed that the poor initial performance of their Chinese counterparts was due, in large, to inadequate nourishment. Sergey Kramarenko, who instructed Chinese pilots, recalls, “The main difficulty for us was the unimpressive physical condition of the students. After a flight in the zone they were completely fatigued and could just barely crawl out of the aircraft. It came to pass that a great deal of serious attention was paid to the rations of Chinese pilots, who were being fed a low-calories diet (of) three bowls of rice a day and a small bowl of soup made of cabbage. After several weeks of increased rations at Soviet jet pilot norms, the Chinese were able hold their own in flights in the zone with our pilots.”

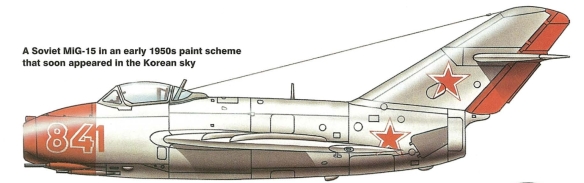

Initially, Soviet combat formations were made up of 24 MiG-15s in three groups of eight aircraft. For reasons of secrecy, all aircraft carried Chinese insignia. Soviet pilots dressed in Chinese uniforms and were even assigned Chinese pseudonyms. They were instructed to speak Chinese or Korean over the air and personal conversations were forbidden. The Soviets believed that if UN listening posts picked up Russian spoken on combat frequencies it would have alerted the UN to their presence.

G. K. Kormilkin, a Soviet MiG pilot, recalled classes for memorizing basic commands in Chinese. Because most Russian pilots had to use Korean dictionaries for even simple phrases, the order was soon abolished. In fact, from the first encounter, most American airmen were convinced that veteran pilots from the Soviet Union flew the MiGs. It is also widely accepted that the United States was engaged in a cat and mouse game and refused to admit how good its communications intelligence was, presumably for the same reasons that the best US bombers were kept in reserve, to monitor and prevent a much more serious nuclear war. A number of American-employed Russian linguists monitored MiG transmissions and, although the Russians were supposed to speak Chinese, they soon learned that it was not an easily assimilated language or suitable for an air-to-air battle command and control.

Radio chatter, the Soviet planners also believed, denied regimental commanders the ability to control the air battle. Only group leaders had the right to transmit over the air, either the regimental commander or, and if the squadrons were operating independently, the squadron commander.

Eventually, the basic Soviet formation in Korea became an element of two aircraft. Two elements made up a flight, two or three flights a squadron. There were three squadrons in a regiment and two to three regiments in a Division. At the top of the organizational ladder was the Corps, made up of two or more Divisions. This particular organization was unique to Soviet forces in Korea. A division would often consist of as few as 48 aircraft rather than the 108 found elsewhere in the Soviet organizational structure.

Although radar simplified the search for the enemy, especially when operating at great altitude or in the soup, the placement of pairs of fighters along the front at different depths and altitudes produced the best results when searching for UN bombers. Opposing enemies in air combat generally saw each other at about the same time. This made the most important factor, the Soviets understood, the fighter pilot’s ability to think. In this respect, Soviet and American fighter pilots shared the same belief.

In a post-glasnost, Russian newspaper interview, Lt. Colonel Smorchkov told the reporter, “Our attitudes towards the American pilots were complicated. During the Second World War, we had been allies against Hitler. Therefore, in Korea, we did not view the Americans as enemies, but only as opponents. Our motto in the air was ‘Competition—with whomever.’”

Before long, the regiment was up against North American-built F-86 Sabres. Their first aerial victory was scored by a Soviet pilot named Akatow, who shot down an F-86 but died of wounds received in combat after only one aerial victory. A short time later, Smorchkov said, his friend, Valentin Filimonow, was shot down by two F-86s.

Other Soviet pilots, including his friends Vladimir Voistinnykh and Pete Chourkin, shared Smorchkov’s opinion that the American pilots were very good. He ranked the F-80 Shooting Star as not very good, the F-84 Thunderjet, average, but the F-86 Sabre, he conceded, was very good. He thought the Soviet MiG-15 was the better aircraft, admitting, however, it had one big problem. The engine would sometimes stop abruptly during a sharp turn.

“One day we attacked a group of Australian Gloster Meteors. They were big, easy targets for us. My friend Os’kin and I destroyed five Meteors during this one fight,” Smorchkov continued. “One night we intercepted B-29 Superfortresses. I was listening to my radio and heard, ‘Group of B-29s in front of you!’ I dove my MiG-15 with my heart pounding. Soon I saw the B-29s with many protecting fighters. I attacked and destroyed two B-29s and one of the escorting Sabres. Over my radio came the question, ‘Alexandr! How are you getting on?’ I answered with a furious, ‘Victory! It’s O.K!’ That night our regiment destroyed five B-29s.” Smorchkov’s newspaper interview concluded: “Before my last flight of the War, my division commander ordered that we were to attack Sabres and then fly back to the USSR. On this flight, I was wounded in the leg. Back in the USSR, I learned that an American pilot with the Russian name, Makhonin, had been captured along with his brand new F-86. It was interesting to study his aircraft up close. Thus, the war was finished for us. However, many of my good friends had perished in Korea and were buried at Port Arthur.”

Smorchkov finished the Korean War credited with twelve victories, five B-29s, two F-86s, and five Meteors.