Also known as Nomonhan, the eastern tip of Mongolia saw a clash between the Soviet Union and Japan beginning on 10 May 1939 as a minor border disagreement and escalating to involve multidivision forces on both sides before ending on September 16. Although the Soviet ground forces decisively defeated the Japanese army, the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force managed to dominate the Red Air Force.

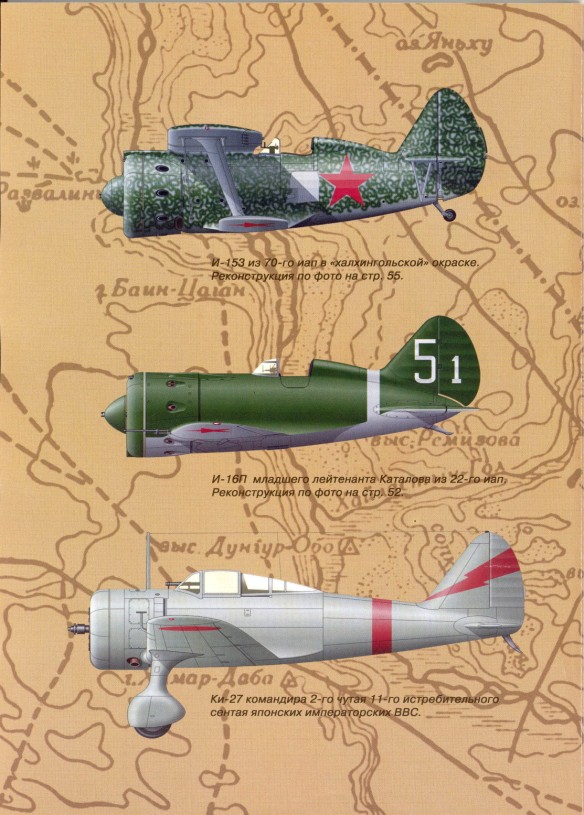

Initially, the Soviets had only 82 aircraft in Mongolia; the Japanese had about 500 aircraft available, but they committed only 32 at the start. Both sides rushed in reinforcements, leading to the largest air battles since 1918, often involving more than 100 aircraft on each side. The Soviets found they were suffering a 3:1 loss ratio and dispatched their most successful veterans of Spain. During the fighting the Soviets introduced the I-153 biplane, the cannon-armed version of the I-16, and made the first ever use of the RS-82 rocket in an air-to-air role.

At first, the JAAF was able to inflict serious losses on Soviet air forces operating over the front; for example, Japanese troops advancing toward the Halha river on July 3

saw Japanese fighters protect infantrymen from about twenty Soviet aircraft which were trying to bomb and strafe the ground troops at low level. When one Soviet aircraft exploded and crashed, the rest fled across the Halha. Encouraged by this successful conclusion to the first clash of arms they had ever witnessed, the troops picked up their pace and covered the ground along the ridgelines more rapidly despite scattered sniper fire.

Although one has to be careful accepting outright victory/loss figures from Japanese and Soviet accounts, it is worth noting that the Japanese claimed to have shot down 481 Soviet aircraft for a loss of 41 of their own during July, a 12: 1 kill ratio. But this dipped even by Japanese sources to slightly less than 6: 1 during August. Soviet figures differ greatly, admitting a 4: 1 loss ratio to the Japanese for May, a 3: 1 victory ratio in June, a 4: 1 victory ratio in July, and a 10: 1 victory ratio in August. The truth, of course, necessarily lies between the two sets of figures; presuming an equal tendency to exaggerate, one may conclude that the true July figures were probably about 3.25:1 in favor of the Japanese, while August was about 1.57: 1 in favor of the Russians. Thus, while the Japanese shot down more aircraft at Nomonhan than did the Soviets, over time they began to lose the air superiority war, and with it the opportunity to ensure that their own bombardment forces could participate in the air-land battle. Further, Japanese forces had to draw upon units and equipment in China, and upon new production straight from Japan, substantially lessening their chance for winning the China war. With a smaller pool of available airmen, losses had a greater impact than with Soviet air forces, while the Soviets had the opportunity of rotating in large numbers of fresh aircrew built around a core of veterans of the Spanish war and utilizing the latest production models of the 1-16 and 1-15 family, including ten I-16’s capable of firing 82mm RS 82 solid-fuel air-to-air/air-to-ground unguided rockets, and the new-and ultimately disappointing-1-153 biplane. These aircraft had little difficulty gaining superiority over the older Kawasaki Ki-10 fighter biplane, and their numbers advantage helped overcome the performance advantage of the later Nakajima Ki-27 fighter monoplane.

Zhukov’s aggressive command style, coupled with the infusion of air and armor personnel with combat experience in Spain (and serving under Spanish war veterans such as air chief Schmutchkievich and armor expert Dimitri Pavlov), quickly resulted in Japan’s offensive being blunted and reversed. While Japan had done well in the initial air war, Japanese ground units were roughly handled by their Soviet opposites, and as fighting extended into July and August, the pace of war intensified, particularly as the Russians resorted to combined armor and air attacks such as one on July 3, when a Japanese regiment was attacked by tanks and seventeen I-16 fighters. By the end of the month, Japanese division commanders were openly admitting the superiority of Russian low-level ground-attack tactics to those of the JAAF. Typically the Soviets would use combined artillery and air assault to fix the enemy and hold him until Soviet infantry-armor forces could fight and finish him.

When the massive Russian-Mongolian offensive of August 20, 1939 began, Zhukov started artillery preparation at 5:45 in the morning, with the guns concentrating on Japanese antiaircraft and machine gun positions. At 6:30 (with, as Zhukov recalled, “the roar of our aircraft . . . becoming ever more deafening”), 150 bombers and 100 fighters attacked Japanese positions between the Halha and Holsten rivers, occasionally bombing on smoke markers fired by Soviet artillery. The bombardment and ground-attack operations paused for an intensive artillery and mortar assault at 8: 15; at 8:30 the air assault resumed and continued when, at 8:45, red signal rockets announced the advance of Soviet ground forces. Zhukov recollected:

The strike of our air force and artillery was so powerful and successful that the enemy was morally and physically suppressed and during the first hour and a half could not even open artillery fire. The observation posts, communications lines and fire positions of Japanese artillery were destroyed.

Zhukov’s memoir likewise quotes from the diary of a certain Japanese officer Fakuta, who perished in the attack:

The fighter and bomber planes of the enemy, some fifty of them, appeared in the air in groups. At 6:30 a. m. the enemy artillery opened massive fire. It is horrible. The observation posts are doing everything possible to spot the enemy artillery, but without any success, because enemy bombers and fighters bomb and shell our troops. The enemy is triumphant all along the front. . . .

[On August 21] A multitude of Soviet-Mongolian aircraft are bombing our positions, their artillery is worrying us all the time. After the bombing raids and artillery fire the enemy infantry charges to attack. The number of the killed is increasing. During the night the enemy aviation bombed our rear positions.

The ferocity of the Soviet assault stunned the Japanese, who wondered where their own aviation and armor forces were; so unexpected was the attack that Japanese reconnaissance pilots had difficulty persuading their headquarters that a Soviet infantry-armor assault was underway, recollecting Hans Kundt’s unwillingness to believe his own air recon during the Chaco war. After an abortive attempt to neutralize Soviet air power by striking at Soviet bases, the JAAF played an increasingly ineffectual role in the battle. Zhukov’s forces rapidly turned the southern Japanese flank, destroying the Japanese Army’s 23d Division in the process, fought a more protracted northern battle before rolling up the right flank, and might well have destroyed the entire 6th Army, except that Soviet forces were under orders not to extend their assault beyond the recognized border between Mongolia and Manchukuo. As at Changkufeng the previous year, a cease-fire on September 16 brought Nomonhan to an end. It had been a brutally instructive lesson for the Japanese government which sought, from that point onward, to do everything possible to ensure peace with the Soviets-a fact that the Sorge spy ring in Tokyo picked up subsequently and transmitted to Stalin, easing his concern over fighting a two-front war once Germany invaded Russia in 1941. For the Soviets, Nomonhan confirmed in a way that Spain had not-and could not-the basic soundness of evolving Soviet air-land battle strategy. Zhukov’s next command following Nomonhan was command of the Kiev Military District; following an influential war game in December 1941 (where Zhukov played the role of an attacking German force, uncannily highlighting some of the very problems Soviet defenders would encounter six months later), the Politburo appointed him as Chief of the General Staff. He would subsequently have numerous opportunities to duplicate his pattern of attack-and his success at Nomonhan-in a game of far higher stakes.

I-16

From 1937 onwards the I-16 was supplied by the Soviet Union to China, which was fending off Japanese aggression; 216 examples were delivered by September 1939. Initially the I-16s were flown by Soviet pilots but gradually, Chinese airmen took over as more converted to the type. Air engagements were fought with mixed results but, following the arrival of the Nakajima Ki-27 in 1939 and the Mitsubishi A6M Zero in 1940, the Japanese turned the tide of battle. By this time, Soviet pilots had been recalled from the country. Meanwhile I-16s continued to operate in small groups as well as singly in China until 1944.

At the height of battle during 1939, Soviet pilots encountered the Japanese at Khalkin-Gol in Mongolia. This short war became well known due to the mass deployment of aircraft from both sides, in the hope of attaining the upper hand in the skies. During the first clashes, the Japanese gained superiority, but this soon swung in favour of the Soviets, who had an advantage over the Ki-27 up to an altitude of around 13,000ft.

The Khalkin-Gol conflict ended with a resounding victory for the Red Army after an effective ground-based offensive. Despite this, the Soviets lost 207 aircraft, half of those being I-16s. The Japanese had 162 aircraft destroyed – with 74 written off as a result of battle damage.

#

Throughout the battle both sides exaggerated their claims. The Soviets claimed 645 victories for 207 losses, and the Japanese claimed 1,260 victories 162 losses.

Japanese aircraft losses

| Ki-4 reconnaissance aircraft | Ki-10 biplane fighter | Ki-15 reconnaissance | Ki-21 high speed bomber | Ki-27 fighter | Ki-30 light bomber | Ki-36 utility aircraft | Fiat BR.20 medium bomber | Transport aircraft | Total | |

| Aerial combat losses | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 62 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 88 |

| Write-offs due to combat damage | 14 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 34 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 74 |

| Total combat losses | 15 | 1 | 13 | 6 | 96 | 18 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 162 |

| Combat damage | 7 | 4 | 23 | 1 | 124 | 33 | 6 | 20 | 2 | 220 |

Soviet aircraft losses