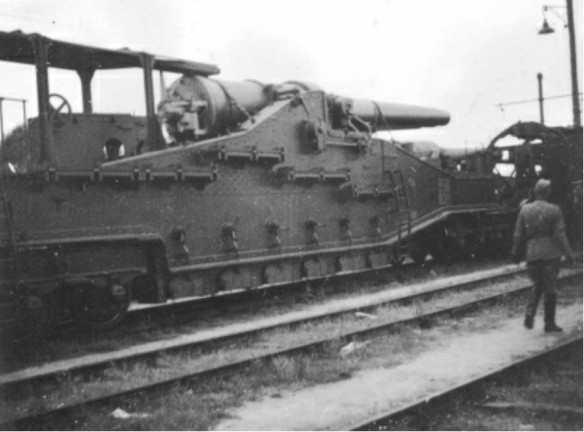

Amongst the siege guns Manstein would bring were French railway guns similar to the one seen here, a 240mm piece. The siege batteries were under the command of HArKo (Higher Artillery Command) 303. They were to have been deployed to neutralize the artillery on Kronstadt Island naval base which supported the Oranienbaum bridgehead. However, limited ammunition restricted their value.

The Oranienbaum enclave had assumed the mantle of bridgehead by the spring of 1942. The designation of Eighth Army had been transferred to a unit on the Volkhov Front. Now known as the Coastal Operational Group, it was well dug in and demanded the attention of German forces to the rear of the main front every time there was an offensive by either side. It was foolish of the Germans to ignore it for so long. Here an anti-tank rifle covers what is doubtless a heavily mined section of road.

One of the first arrivals from Eleventh Army was 5th Mountain Division. The mountain troops were placed in support of the forces along the Siniavino Heights. Here a 105mm mountain gun is prepared to fire. During the summer period this division suffered some 2,000 casualties and lost over 25 per cent of its horses, reducing its mobility severely.

General Erich von Manstein, seen here in the siege lines around Sevastopol, was familiar with the Leningrad Front having served with AGN at the start of the siege. The greater part of Germany’s super heavy artillery had been committed to the reduction of Sevastopol. Now much of it would be brought to bear on Leningrad. Eleventh Army began to move north when Sevastopol fell on 4 July.

The Leningrad front from May 1942 to January 1943.

Even Hitler, who had taken the role of Commander of the German army in December 1941, was aware that his forces on the Eastern Front were incapable of undertaking a massive operation across the whole length of the line. Therefore, despite a huge influx of reinforcements from Romania, Hungary and Italy, there was to be one major offensive, Operation Blue (Blau), the drive to the Caucasus. All other sectors in the USSR were to be sidelined. There were two major thorns in the Axis’ side that needed to be tidied up – the ongoing sieges of Sevastopol and Leningrad. Consequently, OKH (the German High Command) decreed, with the Fuhrer’s approval, that they would postpone, `the final encirclement of Leningrad … until … sufficient force permits’.

The planning of Operation Northern Lights (Nordlicht) had begun earlier in the year. It was an ambitious offensive that envisaged AGN’s two armies, Sixteenth and Eighteenth, each mounting an offensive. Sixteenth Army would attack southwards, coordinating with AGC to eliminate the Soviet forces in and around Kholm thus relieving the pressure on Smolensk and AGC’s rear. Eighteenth Army would breakthrough out of Pushkin into southern Leningrad, culminating in the occupation of the city. Planning on two minor operations, Beggar’s Staff (Bettelstab) to deal with the Pogoste salient, and Moor Fire (Moorbrand) to liquidate the Oranienbaum bridgehead, now held by the Coastal Operations Group, was now also complete. Hitler agreed to send General Erich von Manstein’s Eleventh Army and its siege train of super heavy artillery to facilitate Operation Northern Lights when its present mission, the capture of Sevastopol, was concluded.

Stavka’s orders to Leningrad Front were for more immediate execution – Second Shock Army was to be rescued. Khozin (now commander of Leningrad Front) suggested that it would be sensible to combine the rescue mission with an operation to open up a land corridor by driving the Germans from the Siniavino region. Moscow agreed and began to dispatch reinforcements. Second Shock Army was expected to fight its way towards the relief force, which it would undertake from 20 May. To prevent Vlasov’s escape Eighteenth Army was instructed to destroy it completely. By 31 May Second Shock Army was thoroughly cordoned off but continued to attack furiously.

Re-establishing the Volkhov Front on 8 June, Stalin replaced Khozin on the Leningrad Front with Lieutenant General L. A. Govorov. Despite these moves Vlasov’s troops still remained cut off and order rapidly collapsed during the course of the next four weeks.

At a meeting with Hitler von Kuchler ran his plans past the Fuhrer, who decided to consider them. While the Commander in Chief of the German army debated, AGN held off several attacks in the Pogoste area, but the Soviet’s efforts were not diminishing and it was becoming clearer that they were preparing for another major offensive. On 23 July Hitler announced his alterations to AGN’s summer plans by insisting that Leningrad be taken by September that year. In brief, Northern Lights became Operation Fire Magic (Feurzauber). Operations Moor Fire and Beggar’s Staff were to be undertaken promptly. However, Kuchler managed to convince Hitler that these operations were beyond the capabilities of AGN as it stood and it would therefore be necessary to await the arrival of Eleventh Army. In a calculatedly insulting move von Manstein was given operational control of Operation Northern Lights, as it had become once more and directly answerable to OKH over Kuchler’s head with the remit to flatten Leningrad and meet up with the Finns. Von Manstein’s HQ staff finally arrived in AGN on 27 August. However, by then the situation had altered radically.

During July Soviet intelligence noted German forces assembling between Chudovo and Siniavino which triggered Leningrad Front to carry out spoiling attacks. These were undertaken by Forty-Second and Fifty-Fifth armies and continued with the useful effect of drawing Eighteenth Army’s assets to the threatened points. Stavka, however, wanted more – a complete pre-emptive offensive by both Volkhov and Leningrad fronts in the region ShlisselburgSiniavino. Leningrad Front’s Fifty-Fifth Army and Neva Operational Group would take Siniavino, connecting with Volkhov Front’s Eighth Amy further west, while the reformed Second Shock Army would fight its way into Krasny Bor to meet forces moving out from Leningrad. The earlier attacks had forced Kuchler to use early arrivals from Eleventh Army to bolster his defences. The distance separating the attackers from Leningrad and Volkhov fronts was roughly 20km but marshes and forests benefitted the defenders, as events would show.

As if timed to perfection Manstein’s arrival coincided with the opening of Volkhov Front’s offensive – Eighth Army broke into the German lines at the boundary of 227th and 223rd Infantry divisions. The snail’s pace of the advance brought them to the slopes of the Siniavino Heights some 6km from the rear of the German front on the banks of the Neva River facing Leningrad. But the penetration was narrow and the flanking units were unable to push through German strongpoints at its base. Additional forces were being fed into the area thus the defence was growing stronger. Incredibly, Meretskov repeated his mistakes of earlier in the year by committing his reserves in piecemeal fashion. On the banks of the Neva River Govorov’s troops had established a shaky bridgehead, but could only just hold on let alone expand towards the Volkhov Front’s spearhead, which was less than 5km away, when the Germans counter attacked at the base of Eighth Army’s salient. On 12 September 12th Panzer, 24th and 170th Infantry divisions attempted to cut off Eighth Army but failed. As the fighting continued von Manstein concentrated his forces and added two more infantry divisions and by 25 September had sliced through the neck of the salient. The following day Govorov, at heavy cost to the assault troops, managed to expand the Neva bridgehead but it was too late. The attack was contained by the forty tanks of 12th Panzer Division and Fifty-Fifth Army pulled back across the river within a few days.

On 29 September Stavka ordered Volkhov Front to pull out of the Siniavino pocket. Thousands of Soviet troops managed to escape through the German lines. However, in keeping with his aggressive reputation, Meretskov pleaded with Stavka to allow him to try again. Finally, on 3 October he was refused permission to do anything more than take up defensive positions and allow his men some much needed respite.

During this period of activity von Manstein had modified the overall strategy for Operation Northern Lights. The emphasis was shifted from penetrating Leningrad itself to one of encirclement. Having noted the tenacity of Soviet troops during the final stages of the Sevastopol opewaration, he decided to opt for a wider ranging envelopment of the city by crossing the Neva River some 16km south-east of Leningrad and sweeping up into the rear of Twenty-Third Army that faced the Finns.

Thus isolated from all but air supply Leningrad would therefore be simply starved into submission. To carry out this plan von Manstein requested some 10,000 replacements as the divisions of Eleventh Army had been significantly eroded by the recent fighting. Furthermore, mopping-up operations were going slowly resulting in further casualties. Indeed, Soviet troops would remain at large in the pocket until late October.

As the Soviets dug in so too did von Manstein’s forces. From 14 October AGN resumed the defensive. Operation Northern Lights was postponed and Hitler instructed von Manstein to use his now fully assembled siege train to batter Leningrad into surrender. The bulk of Eleventh Army was to be transferred to AGC commencing in late October, as were divisions from Eighteenth Army. Once again the siege had become a sideshow, a point heavily underscored when von Manstein and his HQ staff were rushed south to deal with the crisis developing along the Volga River at Stalingrad.

While the fighting on land had reduced in ferocity the Red Banner Baltic Fleet had become more active. Soviet submarines had sortied into the Baltic Sea, sinking over 50,000 tons of shipping. In order to prevent such an episode recurring and threatening Swedish iron-ore shipments to the Reich a 48km anti-submarine net was laid across the outlet from the Gulf of Finland. This, along with an increase in the minefields, effectively penned the submarines until the autumn of 1944. This did not prevent the capital ships from providing invaluable supporting fire to land operations from the relative safety of the Neva River and Kronstadt. Heavy naval guns from the training and proving grounds were also pressed into service.