The Celts in Italy: 400–180 BC

The initial Celtic settlement of the Po valley at the end of the fifth century brought the invaders hard up against the barrier of the Apennines—a barrier permeated by well-trodden routes linking the Etruscan-dominated north to the Etruscan homeland backing onto the Tyrrhenian Sea. Inevitably Celtic war bands were drawn southwards into the heart of Etruria. This occurred at the moment that Rome, expanding her power northwards, was taking over the old Etruscan cities one by one. The clash that followed is recorded in some detail by Polybius and by Livy, though offering slightly different chronologies.

The first stage of the southern thrust brought the Celts to the Etruscan town of Clusium in 391 BC, where their principal demand was to be assigned land to settle. Roman ambassadors were sent to act on behalf of the city, but negotiations broke down and in the ensuing battle the ambassadors, in breach of accepted custom, joined in the melee, one of them killing a Celtic warlord. The Celts’ demand for recompense was ignored by the Roman authorities, thus hastening the next stage of the Celtic advance—the march on Rome.

In July 390 (Livy’s date; Polybius says 386), at the Tiber tributary the Allia, the Roman army was destroyed and the city, all except the defended Capitol, fell. The sack of Rome was followed by months of uncertainty, with the Celtic warriors camped around the city growing increasingly restive as they suffered waves of disease. Eventually an agreement was reached and the Celts departed with 1,000 pounds of gold given by the thankful Roman authorities. It is possible that news of aggressive moves by the Veneti on the eastern border of the Po valley settlements may have encouraged their departure. A more likely explanation is that the rapid advance of 391–390 was little more than a series of exploratory raids from the home base north of the Apennines, and, with honour, curiosity, and the desire for spoils assuaged, the warring bands could return home satisfied.

The devastating blow to Rome’s power and authority was in part responsible for the unrest which gripped central Italy throughout the next half-century or so, during which time Celtic raids and Celtic mercenary forces made intermittent appearances, best understood as examples of the Celtic raiding practices described earlier in this chapter. Expeditions of this kind may have been constantly mounted by the tribes settled on the Apennine flank. The more ambitious and deep-thrusting of these raids brought the Celts into episodic contact with Roman forces.

Celtic mercenaries were an altogether different matter. Bands of Celtic warriors willing to fight were available for employment and were seen as a useful resource by aspiring tyrants. One such man was Dionysius of Syracuse, who, having gained control of the Etruscan port of Adria, established a colony further down the coast, at Ancona, in the territory occupied by the Senones. Ancona provided a convenient base from which to enlist Celtic mercenaries. An alliance was struck in 385, and one band of mercenaries, returning from action in southern Italy, joined Dionysius’ naval expedition in an attack on the Etruscan port of Pyrgi in 384–383. Thereafter Ancona continued to provide Dionysius and his son with mercenaries for thirty years. For the most part they served in Italy, but one force was transported to Greece in 367 to take part in the conflict of Sparta and her allies against Thebes. Livy also mentions the presence of Celtic armies in Apulia, one of which moved against Rome in 367. The fact that another attack came from the same area in 149 might suggest that there may have been a long-established Celtic enclave in the area, but there is little archaeological evidence for this, except for the rich grave of Canosa di Puglia with its extremely fine Celtic helmet dated to the late fourth century BC.

By the 330s Rome had recovered sufficiently to begin a new expansionist drive, and, to secure its northern frontier, a peace treaty was negotiated with the Senones in 334. The peace was short-lived and Celtic attacks became frequent and serious, but the situation was temporarily stabilized when, following a defeat of the Senones in 283, Rome founded a colony on the coast at Sena Gallica on the estuary of the river Misa. The Boii reacted by joining with the Etruscans in a move on Rome, but were defeated and cut to pieces near Lake Vadimone. The peace treaty which the Boii were persuaded to sign with Rome was to last for forty-five years.

After the First Punic War (264–241 BC) Rome’s attention turned once more to the north, seen to be Rome’s Achilles heel, and in 232 the territory of the Senones was confiscated and made over to Italian settlement. Further Roman activity in the western Apennines alarmed the neighbouring Boii. Strengthened by a large force of Gaesatae—mercenary Celts from beyond the Alps—the Boii, the Insubres, and the Taurisci began a long march on Rome through Etruria. In 225 at Telamon on the Tyrrhenian coast they were caught between two Roman forces. Polybius’ account of the battle (Hist. 2. 28–3. 10) provides a vivid impression of Celtic warfare. He describes how the Celtic army drew up its ranks to face the attacks coming from two directions, with the wagons and war chariots on both wings and their booty stacked well protected on a nearby hill. The Insubres and Boii wore their breeches and light cloaks, but the Gaesatae fought naked. The Romans were

terrified by the fine order of the Celtic host and the dreadful din for there were innumerable trumpeters and horn-blowers and … the whole army were shouting their war cries at the same time. Very frightening too were the appearance and gestures of the naked warriors in front, all in the prime of life and finely built men, and all the leading companies richly adorned with gold torcs and armlets.

The Romans, impressed by the sight of the gold, took courage and battle commenced. Eventually Roman might prevailed and the Celtic force was destroyed. Estimates of numbers taking part in ancient battles are notoriously unreliable, but Polybius records that the Celtic force comprised 50,000 infantry and 20,000 horse and chariots. Of these about 40,000 were slain and 10,000 taken prisoner. It was a defeat on a grand scale: thereafter Celtic attacks from the north were much reduced.

The Roman triumph was quickly followed up with campaigns in Boian territory in 224 BC and among the Insubres in 222. The foundation of two Roman colonies in 218, among those friendly Cenomani who had taken no part in Telamon, marks a tightening of the Roman hold on the Celtic Cisalpine homeland.

After the Second Punic War (218–202), in which Celts had been employed by Hannibal as somewhat ineffective mercenaries, the Roman armies moved quickly to subjugate the Po valley. The Cenomani who had been hostile to Rome made their peace in 197 BC; Como was taken in 196; and in 189 a colony was founded at Bononia (Bologna). As a result of these campaigns, many of the Boii decided to migrate northwards, back into Transalpine Europe. But Celtic migrations from the Transalpine region were not entirely at an end, for in 186 a Celtic horde including 12,000 fighting men moved through the Carnic Alps intending to plunder and settle. The Roman army intervened in 183: those Celts who survived the confrontation were forced to return home. While not a major event in itself, it was a reminder to the Romans that history might repeat itself and that the only sure defence was the thorough Italianization of Cisalpine Gaul.

HEADHUNTING

The male human head is an image that recurs again and again in Celtic religious art. Everything that made a man what he was resided in his head; it was the seat of the soul. When a warrior killed his enemy in battle, he owned the body of his victim and could dispose of it as he wished. It was his privilege, his right, to take the head if he wanted it as a battle trophy.

This widespread custom appears frequently in accounts by early historians. Here is one, by Diodorus Siculus, writing in about 40 BC:

They cut off the heads of enemies killed in battle and attach them to the necks of their horses. The bloodstained spoils they hand over to their attendants and carry off as booty, while striking up a paean and singing a customary song of victory; and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses just as do those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting. They embalm the heads of their most distinguished enemies in cedar-oil and preserve them carefully in a chest, and display them with pride to strangers, saying that one of their ancestors, or his father, or the man himself, refused the offer of a large sum of money for this head. They say that some of them boast that they refused the weight of the head in gold, thus displaying what is only a barbarous kind of magnanimity.

Strabo repeated this account almost word for word, but adding that Posidonius, whose lost work was used by both writers, had actually seen such heads on display in many places when he had traveled through southern Gaul. According to Strabo, Posidonius had initially been disgusted by the sight, but had got used to it.

It was important for a warrior to take home the head of an enemy, not least because he had to prove that he was brave and strong—and victorious. The Celts were great tellers of tales, but tall tales of a distant skirmish were not enough. The bloody head of an enemy warrior said 1,000 times more; it was incontrovertible. Probably the heads of important enemies were valued more highly, and above all the heads of the chiefs, the battleleaders. The fact that the heads were preserved and kept shows that they might be needed to provide evidence (to the skeptical?) of past bravery in later years.

Before the military engagement at Sentinum in Italy in 295 BC, the Roman historian Livy writes that the consuls received no news of the disaster that had overtaken one of the legions “until some Gallic horsemen came in sight, with heads hanging at their horses’ breasts or fixed on their spears, and singing their customary of triumph.” The heads were not ornamental; they were symbolic. No doubt the best warriors built up substantial collections of preserved heads and they would have done the boasting without any need for words.

This practice was very widespread across Iron Age Europe, not just in the lands of the Atlantic Celts. The Romans liked to think this was a barbarous practice and Strabo declared that the Romans put a stop to it. We forget, and sometimes the Romans themselves chose to forget, that the Romans were part of that Iron Age world and had absorbed many of its customs; they liked to think of themselves as civilized and the rest of the world as barbarian. But occasionally they too took heads as trophies.

Headhunting by Romans is shown in three scenes on Trajan’s Column: on the Great Trajanic Frieze and other carvings celebrating Trajan’s victory in his two Dacian Wars (AD 101–102 and 105–106). In two scenes on Trajan’s Column, a couple of soldiers offer freshly severed heads to Trajan, who seems to reach out with his right arm to accept them. In a battle scene, a Roman soldier clutches between his teeth the hair of an earlier victim’s head, while dealing with a second opponent. In the third image, a soldier climbs a scaling-ladder, holding on his shielded left arm a severed head as he does battle with a defendant on the battlements. As legionaries construct a road, behind them stand severed heads impaled on poles. This has been explained in terms of the Roman army using Celtic units to whom this would have been normal practice, but the practice was evidently condoned—not least in the formal commemoration of the warfare on Trajan’s Column.

Perhaps surprisingly, Julius Caesar does not mention headhunting by the Gauls, but he does say in a reminiscence about Spain that after a victory outside Munda in 45 BC his own troops built a palisade decorated with the severed heads of their enemies. The soldiers who carried this out were “Roman,” but Caesar says they are Gauls of the Larks, the Fifth Legion conscripted by him in Gaul some years before. So the practice of headhunting may on that occasion have been associated with the Celtic recruits, the levied auxiliaries, rather than the regular Roman soldiers. But the Trajanic Frieze shows members of Trajan’s own mounted bodyguard with severed heads, so regular Roman soldiers were involved as well, and with the emperor’s blessing.

In 54 BC, Labienus launched his troops at Indutiomarus, the chief of the Treveri. The Roman soldiers succeeded in killing the chief and cutting off his head, which they took back to the Roman camp. This brutal gesture had the desired effect: when the Gauls heard that the Romans had the head of Indutiomarus, they gave up the fight. They understood; it was a case of the Romans giving the Treveri a taste of their own medicine.

We know from archeology that severed heads were carried home and carefully stored, some to be set up in niches in shrines and temples and offered up to the gods. The imposing stone shrine at Roquepertuse in Provence has in its walls skull-shaped niches that were specially made to display severed human heads. The surviving skulls at Roquepertuse belonged to strong young men in their prime, evidently warriors, and they date from the third century BC. At the sanctuary of St. Blaise, again in Provence, there are also niches for displaying heads.

Many shrines carried representations of severed heads carved in low relief in stone or wood. At Entremont, also in Provence, a stone slab taller than a man is covered with very stylized severed heads; it apparently represents a niche wall. One of the actual skulls at the Entremont shrine was nailed onto the wall and it still has a javelin-point embedded in it—a clear sign of a battle victim.

The presence of stone heads as well as real human heads shows that the offering of severed heads as battle trophies was absolutely essential. If by any chance the supply of real heads dried up, or the shrine was desecrated and robbed, the stone heads could still stand duty as symbolic offerings to the gods. At Entremont there is a fine life-sized statue showing a warrior god sitting cross-legged: a typical Celtic position. His left hand rests on a severed human head; is this the trophy he wants to be offered, or is he showing his people the trophy head that he himself has harvested to keep the tribe safe? The image could be interpreted either way.

When Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni, was enraged at the way she and her family had been treated by the Romans, she led a rebellion during which her warriors took their trophies in the form of severed heads. During the rebellion, Colchester was destroyed and London attacked, and the fires that the Britons started left a red, burned layer across the City of London that is still clearly identifiable as “Boudicca’s Destruction Layer” and datable to AD 61. The Walbrook Skulls are believed to be some of the severed heads of Londoners massacred by Boudicca at that time.

Folk-tales carry within them vivid memories of headhunting. In the ancient Irish epic, the Tain, we hear of the youthful hero, Cú Chulainn, taking heads as trophies. He decapitates the three sons of Nechta: the formidable warriors, Fannell, Foill, and Tuchell, who boasted that they had killed more Ulstermen than there were Ulstermen surviving. On his return, wildly triumphant, to the fortress at Emain Macha, a woman there looks out and sees him riding toward the stronghold. She cries, “A single chariot-warrior is here … and terrible is his coming. He has in his chariot the bloody heads of his enemies.”

The Romans never conquered or occupied Ireland, or even attempted it, so they would never have seen Irish warriors behaving like this, but they saw it elsewhere, and they always deplored it. They made a point of deploring this universal Celtic custom, even though they occasionally did it themselves. Headhunting, like human sacrifice, was one of the badges of barbarism. It was just not the Roman thing to do (officially).

In Welsh storytelling, we find the same emphasis on the severed head, and its special magical quality, but with a twist. In the Mabinogion, the hero Bran is mortally wounded. He asks his companions to cut off his head and carry it with them on their travels as it will bring them good fortune:

“And take you my head, and bear it even unto the White Mount in London, and bury it there with the face towards France. And a long time you will be upon the road. And all that time the head will be to you as pleasant company as it ever was when on my body.”

After decapitation, Bran’s head goes on talking, which is often a feature of these tales (see Myths: The Ballad of Bran). In Ireland, the head of Conall Cernach similarly had magical powers. It was prophesied that his people would gain strength from using his head as a drinking vessel.

Turning a skull into a bowl, a magical cult vessel, was evidently something that actually happened in the Celtic world. The Roman historian Livy describes the killing of a Roman general, Postumius, in 216 BC, by a north Italian tribe, the Boii. They beheaded Postumius, defleshed the head, cleaned it, then gilded it, and used it as a cult vessel. Livy also described the Gauls taking the heads of their enemies in battle, and either impaling them on their spears or fastening them to their saddles.

The cult of the head was taken over in the Christian period in stories about the early saints. As soon as a severed head appears in a story, its archaic reference back to an Iron Age pagan world is obvious. St. Melor was one of these Dark Age saints, venerated in Cornwall and Brittany. He met his death by decapitation, but then his severed head spoke to his murderer, telling him to set it on a staff stuck in the ground. When this was done, the head and staff turned into a beautiful tree, and from its roots an unfailing spring began to flow. The biblical story of Aaron’s Rod was filtered through Celtic pagan lore.

A Scottish folk-tale tells of the murder of three brothers at the Well of the Heads. Their bodies were beheaded by their father. Three prophecies were uttered by one of the heads as it passed an ancient standing stone. The head declared that its owner, when living, had made a girl pregnant and that her child would one day avenge its uncles’ deaths. When the boy reached 14, he did indeed behead the murderer, and threw the head down a well. The severed head, the ancient stone, the well, kinship, revenge, and the rule of three—all the ingredients of this story from the Western Isles were drawn from long-remembered Celtic archetypes.

The Celts were not by any means the only headhunters in the world, but they carried the custom to obsessive lengths. There was a universal interest in venerating the human head and acquiring trophy heads; it prevailed right across Iron Age Europe. If one single belief can be claimed as pervading Celtic superstition, it must be the cult of the severed head.

CHARIOTS

Chariots were used for showing off before battle. Queen Medb of Connaught, for example, was driven in her chariot around her camp as a prelude to battle.

Here is what Julius Caesar had to say about the British Celts on the battlefield:

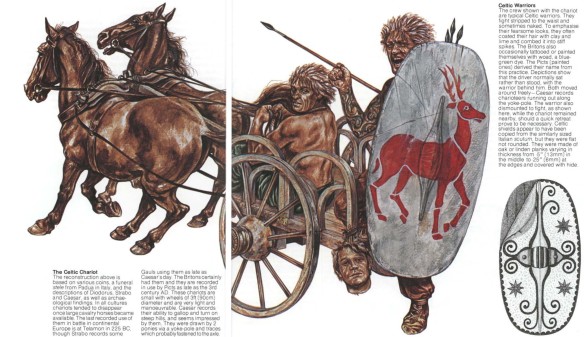

In chariot fighting the Britons begin by driving all over the field hurling javelins, and generally the terror inspired by the horses and the noise of the wheels are sufficient to throw the opponents’ ranks into disorder. Then, after making their way between the squadrons of their own cavalry, they jump down from the chariots and engage on foot. In the meantime their charioteers retire a short distance from the battle and place the chariots in such a position that their masters, if hard pressed by numbers, have an easy means of retreat to their own lines. Thus they combine the mobility of cavalry with the staying-power of infantry; and by daily training and practice they are able to control the horse at full gallop, and to check and turn them in a moment. They can run along the chariot pole, stand on the yoke, and get back into the chariot as quick as lightning.

Caesar saw all this firsthand and he was impressed by what he saw.

Chariots could also acquire cult status. Two Gaulish cult vehicles were imported, dismantled, and buried in a mound with a cremation burial at Dejbjerg in Denmark in the first century BC. There was a throne at the center of each wagon, and the bodies buried at the site are believed to have been female. Were they perhaps warrior queens?

No British Iron Age chariots have survived, though a chariot wheel was found in a second-century rubbish pit. It was a single piece of ash bent in a circle, fixed to an elm hub, with willow spokes. Early Irish folk-tales, such as The Wooing of Emer, from the Ulster Cycle, offer descriptions of working chariots:

I see a chariot of fine wood with wickerwork, moving on wheels of white bronze. Its frame very high, of creaking copper, rounded and firm. A strong curved yoke of gold; two firm-plaited yellow reins; the shafts hard and straight as sword blades.

Though the Celts fought mainly with infantry, cavalry forces were used by many of the tribes. In most cases, these cavalry forces were most likely made up simply of horse-mounted infantrymen. Many Celtic archaeological sites, however, have yielded remains of chariots, which would have been more effective in most battles and would also have required somewhat more skilled handling to use to their fullest advantage. Roman accounts indicate an intriguing tactic employed by the Celts in their chariot warfare of using chariots to deposit soldiers riding on board into enemy ranks. Though such use of chariots was not unheard of in the ancient world, it was much more standard for soldiers to remain on board the chariot while the charioteer drove it through the enemy ranks, rather than jumping off to engage on the ground.