WARFARE

The warrior-prince burials from both Hallstatt and La Tène cultures show an interest in fighting. It looks as if, just as with the Mycenaeans, high status was inextricably tied up with outstanding performance on the battlefield. To be a leader, you had to be a war leader.

The classical writers who described the Celts commented particularly on their aggressive and warlike nature. Diodorus Siculus wrote:

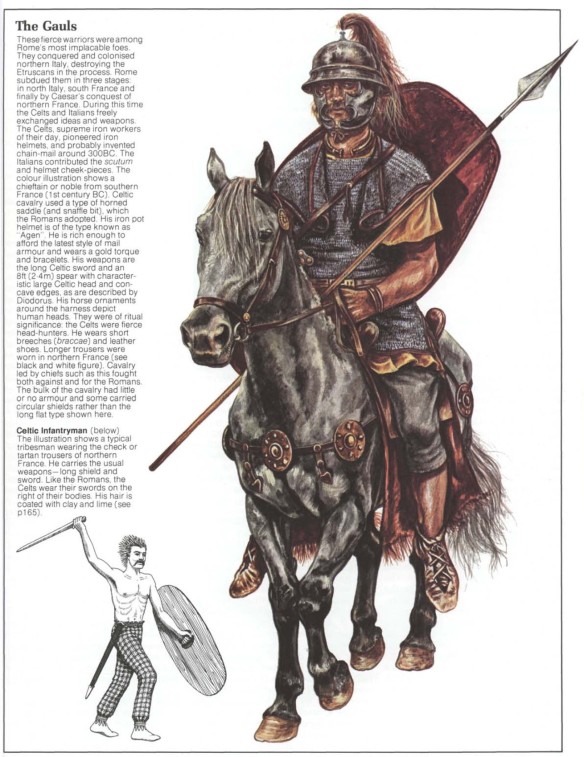

The Gauls are terrifying in appearance, with deep-sounding and very harsh voices… Their armour includes man-sized shields, decorated in individual fashion. On their heads they wear bronze helmets.

Warriors, according to Julius Caesar, acquired status above that of freeman. Warrior-princes rode to battle in chariots, collected the heads of enemies as trophies, performed feats of skill and engaged continually in individual duels as well as skirmishes.

There are many bronze figurines to show us what Celtic warriors looked like in action. A third-century BC spearman (found near Rome) is naked apart from a torc, a horned helmet, and a belt. The belt, which was commonly worn even by warriors who were otherwise naked, has rarely been commented on. It was worn to hold a knife, sometimes tucked through just behind the hip. The knife was used to finish off a wounded enemy—and sometimes to cut off his head as a trophy.

Warriors went into battle looking as ferocious as they could. This meant getting themselves into a strange state of mind and pulling remarkable faces.

Their style of fighting was described by Roman writers, but in contradictory ways. Livy described them as having neither discipline nor strategy and surging about in uncontrollable hordes. But this is in the context of the Celts’ third-century BC invasion of northern Italy, and the Romans were experiencing the sharp end of it. Livy had every incentive to portray this act as a feral attack by a barbarian horde. Caesar gives a very different impression of the Celts in his Gallic War. The Gauls calculate and trick, and carry out some complicated and dangerous maneuvers. They must have been commanded by imaginative chiefs with ideas of strategy and fairly effective chains of command, even if they did not always remain in full control of events.

In the early Iron Age the Celts were individual fighters and skirmishers. They formed recognizable armies only at a late date, though they were able to do this when the crisis was great enough.

Success depended on collaboration. The Celts did form military alliances, and they could present formidable opponents to the Roman legionaries, but those alliances were fragile. In the end, the Romans were able to conquer Gaul and Britain by virtue of the disunity of the Celtic tribes. Tacitus commented, “They eventually failed because they are distracted between the jarring factions of rival chiefs. Indeed, nothing has helped us more in war with their strongest nations [the tribal confederacies of the British] than their inability to co-operate.”

Some of King Arthur’s Wonderful Men was written in the tenth century but based on earlier documents reaching back to the Dark Ages. The warriors described as the members of Arthur’s war-band are colorful, larger-than-life saga heroes. Morfran, son of Tegid, was said to be so ugly that at the Battle of Camlann no man raised a weapon against him, thinking he was a devil. Sandde Angel-Face survived Camlann because he was so beautiful that people thought him an angel. Other men who fought beside Arthur were Gwefl, son of Gwastad, Uchdryd Cross-Beard, Clust, son of Clustfeinad, Gilla Stag-Leg, Gwallgoig, and the three sons of Erim: Henbeddestr, Henwas the Winged, and Scilti the Light-Footed.

Some of the claims made on their behalf were fanciful in the extreme, and perhaps we can hear, dimly, the sort of wild drunken boasting that might have accompanied many a feast. Medr, son of Medredydd, could shoot a wren in Ireland from Kelliwic in Cornwall. Gwaddu of the Bonfire’s shoes gave off sparks. Osla of the Big Knife could bridge a river with his magic knife. Drem, son of Dremidydd, could see Scotland from Kelliwic. Finally, there was Cachamwri, who was Arthur’s servant.

Weapons and armor changed during the Iron Age. In fact on the European mainland there were significant changes even within the La Tène period, about 460 BC to 50 BC. La Tène A1 was a transition from the Hallstatt culture to the solidly Celtic La Tène, beginning in 460 BC. Offensive weapons were dominated by spears. The warriors’ graves were fitted out with several spears: usually a single large fighting spear and several lighter throwing spears or javelins. Swords were usually short side-arms, with blades 16–20 inches (40–50cm) long; these were little more than substantial daggers and designed for stabbing in close-quarter fighting. Metal shield fittings were rare, often only a reinforcement for the grip. It was common for belt-hooks to be made of ornate openwork. At this stage the warrior-elite, the nobles, were fighting mainly from chariots.

By 400 BC, the start of La Tène A2, slight changes were under way. Swords became more common in warrior graves, and with a fairly standard sized blade of 24 inches (60cm). Spears were still very much in use, and often in pairs or larger numbers. The Waldalgesheim Style (or Vegetal Style) appeared. This is used on helmets, scabbards, and personal ornaments, often covering every inch of the object with decorative line. An S-form using dragon or bird images appeared on scabbards. Shields were still mainly organic (wood or leather), but with metal fittings, and sometimes a metal rim. There was a strong emphasis on chariot warfare.

From 300 BC onward (La Tène B), the Celtic warrior reached the height of his power. The most common type of warrior was the heavy infantryman, who fought not only for his own tribe but fought for others as a mercenary. Warrior aristocrats fought as cavalrymen or as chariot warriors; cavalry was on the increase, with chariot warfare now on the decrease. The standard fighting gear was now a single large fighting spear, a sword, and a shield. Swords were now slightly longer, with blades 26 inches (66cm) long, with a midrib, and were heavier. On shields, metal umbos (bosses) began to appear: initially as twin plates nailed to the wooden boss, and later as the strap-boss. Metal rims were still uncommon.

In La Tène C, from 260 BC onward, the standard warrior gear remained the same: heavy fighting spear, sword, shield, and now always an iron belt chain. The infantry were still the most common type of soldier, but cavalry were becoming more important. The typical sword was longer and thinner, a rapier with a blade that was lens-shaped in cross-section; blade lengths vary, but up to 32 inches (80cm) long. Later blades had almost parallel sides. Spears also changed in shape; some developed a long, tapering quadrangular point. The artistic style of this phase was more restrained, with sparer decoration using triskeles and flowing asymmetrical lines.

In La Tène D, which lasted from about 125 BC to AD 100, the Celtic warriors reached their final flowering. Professional warriors included an important class of noblemen who were cavalrymen, and also large numbers of infantrymen who were more lightly armed. The equipment consisted of a long, heavy fighting spear or lance, a long cutting sword, and often a helm. The sword was large and its blade was parallel-sided for most of its length; the point was usually short. This design was less for stabbing, more for cutting, with a blade often 32–6 inches (80–90cm) long.

Shields sometimes had a spindle umbo, but as time passed the spindle disappeared and a domed metal boss appeared. The decorative style became simpler and severer.

Whether the Iron Age Celts were more warlike than other, later peoples is hard to gauge. They had a reputation for being quarrelsome, fierce, and ready fighters. In recent years this warlike image has been downplayed. Even the massively fortified hillforts have been presented as peaceful settlements, with probably a ritual and ceremonial function, with the ramparts put up mainly for show.

But new evidence from Fin Cop, a hillfort in the English Peak District, south-west of Sheffield, shows that forts did have a military function, and that defense against violent attack was very necessary. Fin Cop’s defenses were built in haste in about 420 BC, in response to a real and immediate threat. The defensive wall 6.5 feet (4m) high on the fort’s eastern perimeter was pushed over into the ditch beside it, leveling the fortification. This wall was attacked and destroyed, and its stones pushed on top of the corpses of scores of people. The most gruesome discovery was that of the skeletons that could be identified, all were women and children—none were warriors. They had no bone damage, which suggests that they all died of soft-tissue injuries, perhaps by having their throats cut. It was a massacre of civilians, and it happened within a few years of the fort being built.