Attacks were made on the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Brest again on 9/10 January 1942 in a night sortie. All told, 82 aircraft were despatched. Take off originally was to be at 03.20 hours on the 10th but it was brought forward to 00.04 hours because of weather. Crews had previously been briefed twice for this trip but each time it was cancelled. At take-off it was dark and there was no horizon, with cloud at 1,500 feet. They kept to 1,000 – 1,500 feet to Upper Heyford when the cloud thinned and they went up through it to 7,000 feet. Twenty minutes were spent over the target. Nickels (propaganda leaflets) were dropped but as the target could not be identified they brought their bombs back. Flak was heavy but inaccurate.

In what was a time of general Allied distress at sea. In the European Theater, the notorious Channel Dash of 11-13 February 1942, by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau with an escort of destroyers and aircraft, might be termed a comedy of errors but for the great loss of life-almost all British. Both German warships slipped from their French bases, steamed through the English Channel past slack British defenses, and found haven in Germany. It was the first time since 1588 than an enemy fleet had managed to pass through the English Channel. This, after the Royal Navy had been at war at sea for more than two years. Two days later, on the other side of the world, Singapore ignominiously capitulated.

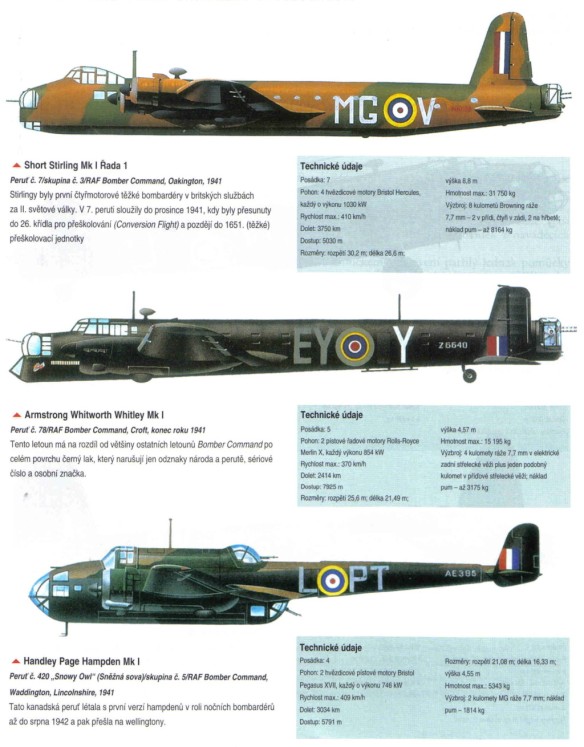

On 12 February – a cold day, overcast, 10/10ths cloud – news arrived at Bomber Command Headquarters soon after 11am that the battle cruisers Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, accompanied by a strong escort of destroyers, R- and E-boats, fighter and bomber aircraft, had sailed from Brest and were moving up the Channel, right under the noses of the British in bad weather and low cloud. The German naval force was obviously making for their home ports. The German warships were not discovered until late that morning when a Spitfire flown by Squadron Leader ‘Bobby’ Oxspring spotted them off Le Touquet. All available Royal Navy and RAF units were ordered to attack the ships before darkness closed in. Most of Bomber Command was ‘stood down’ for the day and only 5 Group was at four hours’ notice. In the largest Bomber Command daylight operation of the war to date 242 bombers and aircraft of Coastal and Fighter Commands and of the Fleet Air Arm made frantic efforts to sink the ships. The attacks were kept up from a little before 3 o’clock in the afternoon to a quarter-past six in the evening, by which time it was almost dark. Icing at times very severe, and rain and hail were met with by most of the crews. All the attacks were in vain. Most of the aircraft were unable to find the German ships and of those aircraft which did bomb, no hits were registered. None of the attacks by other forces caused any serious damage to the German ships, though the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau were both slowed down after striking three mines previously laid by 5 Group Hampdens or Manchesters in the Frisian Islands. Operation Donnerkeil-Cerberus had been a complete success.

One of the aircraft that took part in the ‘Channel Dash’ operation was a 12 Squadron Wellington at Binbrook flown by Pilot Officer ‘Pat’ Richardson DFC RAAF. The crew sighted the Scharnhorst through a break in the cloud. Richardson manoeuvred to carry out an attack, put the Wellington into a steep dive and prepared to dive bomb the battleship. Sparklets of fire flickered from the Scharnhorst’s pom-poms and other AA armament and tracer tore past the bomber’s wings and fuselage as the Germans concentrated their full defences on the audacious attacker. A shell shattered the Wellington’s Perspex, severely wounding Richardson in the left arm. Despite the shock of the wounds he continued to attack. Taking over the observer’s bomb controls, Richardson waited, then pressed the master switch and released a stick of bombs from 400 feet across the Scharnhorst’s bows.

Another Australian in the Wellington attack was Pilot Officer H W Johnstone, whose section became separated from its formation and made an independent attack on the Prinz Eugen and the Scharnhorst. Low, dense cloud all over the sea had made it difficult to find the ships. Flak was coming up through the clouds as Johnstone’s aircraft dived and a fragment of shell hit his arm. The Wellington went on down and the crew saw the Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen about a mile and a half apart, with all their guns seemingly turned on them. The Wellington was hit again and the top of the cockpit above Johnstone’s head was knocked off. An oil pipe was cut out and oil spurted over the navigator. The Wellington did not break cloud suitably for aiming. It rose and was hit in the tail as it did so. Johnstone made one more dummy dive and then tore down at well over 300 mph. The Prinz Eugen’s deck seemed to shoot up to meet them, growing larger every second, with her guns firing steadily. The front gunner said later he found himself leaning to one side of his turret but then he said to himself: ‘You silly blighter; they’ll get you there just as easily.’ He raked the decks of the warship with his gun during the dive and at 400 feet they let the bombs go. Then Johnstone tried to pull out of the dive but the aircraft did not answer at once. He tugged at the stick with both arms and with his feet braced on the instrument panel. The Wellington was only a foot or so from the water when it answered and shot up into the cloud.

A 214 Squadron Wimpy flown by Wing Commander Richard Denis Barry McFadden DFC took off from Stradishall with a seven-man crew and 500lb armour-piercing bombs intended to break through the battleships’ armour-plated decks. Ten-tenths snow-bearing cloud from 900 feet to 9,000 feet prevented any sightings so McFadden bombed on estimated time of arrival (ETA). When the Wellington turned back to fly home it started to ice up very badly. The port engine packed up and after about twenty minutes, part of the propeller broke away and went through the side of the aircraft, damaging the hydraulics. The Wimpy eventually came down in the North Sea at about a quarter to five in the evening. Sergeant Robin Murray, one of the two wireless operators on the crew, recalled:

When we hit, the Perspex area behind the front turret broke and the wave took me right back up against the main spar. I came to, underwater, pulled myself along on the geodetics and came up by the pilot’s controls. There were four of them already in the dinghy, which was still attached to the wing. I was the last one in. We’d lost Flight Lieutenant [Patrick Frederick] Hughes DFC and George Taylor. We paddled around with our hands looking for them, and Sergeant Andy Everett the other wireless operator, swam round to the turret which was under water, because the plane had broken its back just behind the main spar – but it was no good. I had swallowed a lot of salt water and was very sick. We were all sopping wet. We made ourselves as comfortable as we could. There were five of us in the dinghy – McFadden, Stephens [Squadron Leader Martin Tyringham Stephens DFC who had occupied the tail turret], Pilot Officer Jimmy Wood [the second pilot], Everett and myself.

For the first few hours there was nothing around – just the sea. It was quite choppy and that was uncomfortable. Unfortunately, whoever had put the rations in the dinghy had forgotten the tin opener, so we couldn’t open the tins. Then the knife fell overboard, so we didn’t have that either. So all we had was Horlicks Malted Milk tablets. It was cold – the coldest winter for nearly a century. We were hoping that someone would come out and pick us up, because the wireless operator had sent out a Mayday signal – but what none of us realised was that the navigator must have got his co-ordinates wrong. We had done a 180º turn and we were heading out to sea again, so we landed off the Frisian Islands instead of, as we thought, 20 miles off Orford Ness. I had read about how you mustn’t go into a deep sleep when you’re cold, because you get hypothermia and that’s it – you die. So I suggested that we always had two people awake so that we didn’t all go right off into a deep sleep – and that’s what we tried to do.

Everyone survived the first night. We thought that any moment somebody was going to pick us up. We saw quite a few aircraft flying very high – unrecognisable, of course. There were flares on the dinghy, but we didn’t see any aircraft that was low enough to have seen us. Once we thought we saw a ship – that was on the second day. We set off a flare, but nothing happened and we tried to send off another. But it wouldn’t work – it was damp. None of the flares worked at all after that. We saw quite a few aircraft that evening, just before dusk, flying very high. We came to the conclusion they were probably German. We hadn’t got a paddle on board – we were just sitting there. It was very strange, because people just went into a coma. They just sort of lost themselves. Stephens went first, on the second day at 4 o’clock. That second night was very cold. We just talked about various things. There was no despondency – we never thought we weren’t going to be picked up.

At dawn of that morning, Wing Commander McFadden died. There were no visible signs of injury. McFadden was firmly under the impression in his last hours that he was in his car, driving from the hangars back to the mess. He was the only one who got delirious in that way. People sort of went into a coma. They would be talking quite normally – and they would gradually drowse off. You’d shake them to try to keep them awake, but they’d gone. You could feel that they were going. But it was peaceful – there was no suffering at all. They weren’t in pain – they just quietly died. Jimmy Wood died about three hours after Wing Commander McFadden. He was very quiet. Finally, Sergeant Everett died at dawn. I was disappointed that he had gone so quickly. He went while he was talking – just drifted off. I kept them all on the dinghy and was able to keep my legs out of the water by resting them on them. It sounds terrible, but by this time they were beyond help.

The final morning was the worst time, because we drifted in towards land. The water was as calm as a millpond and the cliffs were about 150 yards away, with a gun emplacement on the top. It was about 11 o’clock, I suppose, by the time I drifted into the shore. I got a tin lid and caught the sun and somebody came out of the gun emplacement. Then the tide started to go out. I was starting to drift out to sea. That was a bad moment. Then a German Marine Police boat with a Red Cross came out and they hauled me aboard. I was able to stand up and they got me on to the deck. They tied the dinghy on the back with the bodies of my crew and came slowly back. They took me into Flushing dock. I’ll never forget that moment – the deck was above the quay and they put a ramp down and as I walked down the ramp to the ambulance, there were five or six German sailors there and they all came to attention and saluted me.